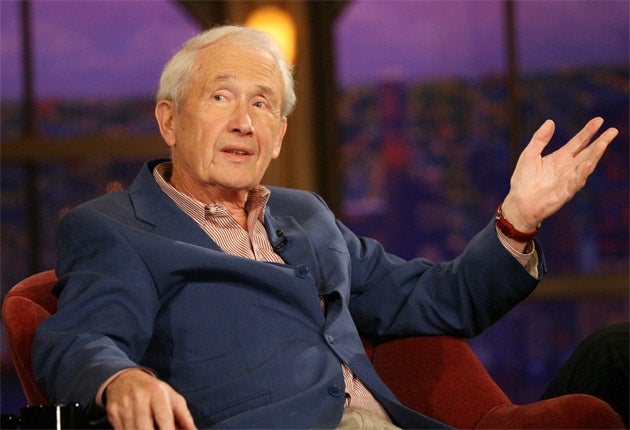

Frank McCourt: Late-flowering writer whose book 'Angela's Ashes' set in train the genre of 'misery memoirs'

To sell four million copies of a memoir which might usefully have carried the health warning: "Can induce nausea", is some achievement. But that's what Frank McCourt did with Angela's Ashes, his account, published in 1996, of an utterly miserable childhood survived in Catholic Ireland in the 1930s and 1940s.

The life which he was to chronicle so vividly in his retirement began in New York on 19 August 1930. His parents were Irish immigrants – his father, Malachy McCourt, was an old IRA man from Co. Antrim, his mother a Limerick girl. They found bringing up children in Brooklyn during the Depression was hard. Malachy drank and sang a lot but worked little. When Frank's young sister Margaret died they shipped themselves and their four children back to Ireland.

But there life was no better. In Limerick Malachy found very little work and the family lived in a succession of damp, primitive houses where the fecund Angela produced more babies. But within two years their twins, Eugene and Oliver, were dead – largely because of the appalling conditions the family lived in. Eventually Malachy left to find work in England and never returned. Frank and his siblings and their indomitable, but often depressed mother, had to make their way on their own.

This is the "miserable Irish childhood" at the core of Angela's Ashes. Yet the book has an extraordinary buoyancy – mainly because McCourt has brilliantly dramatised the voice of young Frank. He plunges us into the story – almost rubbing our noses in the feel, the texture, the smell of unrelenting poverty. There are queasy descriptions of a succession of rented rooms, shared lavatories; flooded living rooms; pigs' head for Christmas dinner, interspersed with the odd miraculous Vienna loaf when, very occasionally, Malachy remained in contact with his earnings and passed them on to Angela. There was a little help from local institutions; more came from people like the coal merchant who, for a pittance, allowed Frank to help him on his rounds.

The warm, dry Catholic churches were often the places of physical refuge for Frank and his brothers. But what he calls "the pompous priests" were of very little help and there are brilliant dialogues as the young and mischievous Frank leads them a merry dance in the confessional. But he does not escape the indoctrination completely. In a remarkable episode towards the end of the book he gets a job as a bicycling deliverer of telegrams. He encounters a beautiful, consumptive red-haired girl; he has got soaked in the rain and fallen off his bike; she invites him in to dry off; "the excitement", as Frank delightfully calls it, gets the better of him – and her.

He is only 14 but they have sex, several times, but she dies within months. Frank is heartbroken but also guilty; he has led Theresa into sin and she will suffer eternal damnation as a consequence. He goes to four masses, does the Stations of the Cross three times, says rosaries all day to pray for the repose of her soul. But it's no good: "I never had a pain like this [before] in my heart and I hope I never will again."

At the end of Angela's Ashes Frank finally gets control of his life and goes off to New York again. Before describing what became a more conventional existence – although one which still has strong picaresque elements – it is worth dealing with the controversy which Angela's Ashes provoked.

It was an instant, word-of-mouth success worldwide, but in Limerick voices were raised. Exaggeration was the charge and pictures were produced showing a plump and healthy-looking Angela, and Frank well-turned out in Scout uniform at the time when they were supposed to be near starvation. There were suggestions that the book sullied "the fair name of Limerick" and even painted an unfair picture of the Limerick girl, Angela. The book contains "remembered" dialogues and there is a sense sometimes of fabulous story-telling rather than a concern for the full picture of how it was.

Nevertheless Frank's family undoubtedly suffered desperately; his parents are given enormous sympathy despite their weaknesses; and there is a good deal of objective evidence showing that poverty of this intensity was experienced when Ireland retreated into its economic shell in the 1930s. Before he died, Limerick and Frank McCourt reached an accommodation.

Away from Ireland and back in New York in 1949 Frank found the American Dream of affluence elusive. He took various jobs – including (according to his later memoir 'Tis, published in 1999) minding canaries for the Biltmore Hotel. He was put in charge of 60 of them; 39 rapidly died, so he taped the corpses to their perches. The ruse did not succeed and he had a chequered employment career until he found his vocation as a teacher. He had been drafted into the army – serving as a dog-trainer and clerk – but the bonus came afterwards when the GI Bill put him through New York University. By the 1950s he was teaching English at McKee Vocational High School in Staten Island and then moved on to the more elite Stuyvesant High School where he taught creative writing with great panache. He gave a lively account of this part of his life in Teacher Man (2005)

Even in the worst moments of his youth McCourt had felt something like a vocation for writing. He used to listen in awe to radio plays – not at home but sitting in the street, hearing the sound come through the windows of a house where there was a radio. Often they were Shakespeare and he memorised lines he barely understood because they sounded so magnificent. And he read eclectically even as a child: Tom Brown's Schooldays, Goldsmith's Deserted Village, P.G. Wodehouse.

It was not until his retirement that he felt able to tell the full story of his childhood. He admitted that he had been "in recovery" from it for 50 years. He and his brother Malachy had already worked over some of the material in a stage show called, A Couple of Blackguards. All that Frank needed to create a memorable memoir was the right "voice" – and eventually he found it in the perfectly pitched voice of a child.

Bernard Adams

Frank McCourt, writer: born New York 19 August 1930; married 1961 Alberta Small (one daughter); secondly Cheryl Floyd; 1994 Ellen Frey; died New York 19 July 2009.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies