George Brecht: Composer and artist with the Fluxus movement who pioneered conceptual art

It was typical of the Fluxus artist and composer-to-be George MacDiarmid that when he changed his surname to Brecht in 1945 – just before Bertolt Brecht premiered The Caucasian Chalk Circle in America – he insisted it had nothing to do with the well-known playwright. Asked why he had chosen the name, the 19-year-old GI, serving in Germany, remarked merely that he liked the way it sounded. For the ensuing six decades, sound was to be George Brecht's bread and butter. "No matter what you do, you're always hearing something," he said, thus explaining a body of work that would come to include a piece of music made with dripping water.

Although his sound art – "music" is perhaps too narrow a term – ended up being even more experimental than that of his mentor, John Cage, Brecht's background was far from avant garde. His father was a classical flautist with New York's Metropolitan Opera Orchestra; the elder MacDiarmid, an alcoholic, died when his son was eight.

Returning with his new name to the US after the Second World War, Brecht went not to art school but to the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science, where he studied industrial chemistry. From his early twenties to the age of 40, he worked as a consultant for such blue-chip firms as Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson.

In his spare time, however, Brecht used the income from such jobs to join a band of radical musicians and artists who were loosely associated with the Fluxus group. In 1958-59, he swapped his lab coat for the jeans and turtlenecks of the New School of Social Research in Greenwich Village, where he was taught experimental composition by Cage.

By 1961, Brecht was teaching in the radical art department at Rutgers University, alongside the likes of Allan Kaprow, inventor of the "happening". In January 1962, Brecht staged a happening – or perhaps a performance, or an event – of his own: Drip Music, scored for "a source of dripping water and an empty vessel... arranged so that the water falls into the vessel". Asked by a bemused critic to explain the piece, its composer remarked: "There is perhaps nothing that is not musical. There's no moment in life that's not musical... All instruments, musical or not, become instruments."

This inclusivity – the itch to "ensure that the details of everyday life... stop going unnoticed" – made Brecht a very modern artist indeed. His work was marked not so much by a blurring of the line between High and Low Art as of that between art and life. Anyone could make a Brecht, even if not everyone could understand why they might want to. Where the previous decade's American artists, typified by Jackson Pollock, had cultivated the myth of Promethean genius, Brecht handed over the glory of making his works to anyone who wanted it.

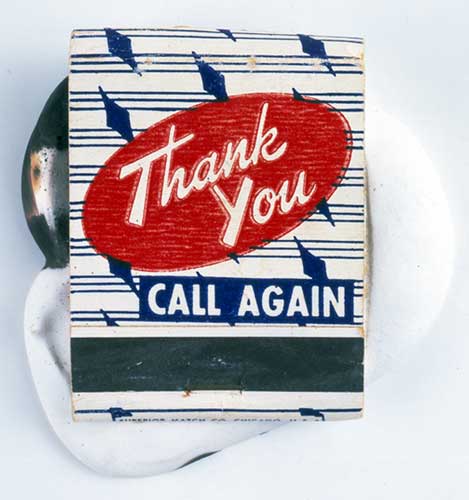

His event scores consisted of small white cards printed with instructions and given to participants. The one for a piece called String Quartet consisted of the words "shaking hands", which was all the musicians performing it were required to do; Chair Events of 1961 – chairs played a central part in Brecht's iconography – consisted of musical scores left on seats. His Water Yam, among the first of those Fluxus works known as "Fluxkits", a box containing cards printed with instructions for short events or activities, undermined the gallery system by trading simply in ideas. From Brecht's experiments of the early 1960s descends the whole of modern conceptualism, although Sol LeWitt, the so-called "father of conceptual art", didn't coin the term until 1967.

Through all this, Brecht continued to work as a research chemist. Although the two halves of his professional life seem curiously ill-matched, his art bore clear signs of his science. His own performance of Drip Music used laboratory pipettes for the dripping and Brecht's paintings of the late 1950s – the medium was soon discarded as too limiting – were made using a kind of titration process. At various times, he assembled cabinet pieces (or "event objects") in which the taxonomic ordering of the contents was more important than the contents themselves. Damien Hirst's Pharmacy cabinets, made three decades later, do much the same thing.

Brecht's classically musical father also puts in an appearance in his son's anti-classical work, in a piece called Flute Solo (1962). The Fluxus artist, in a rare moment of self-revelation, recalled his long-dead parent in mid-nervous breakdown, taking his flute apart in the middle of a performance. The event score to this particular event required the performer to do the same.

Although Brecht was arguably more radical than Cage or LeWitt, his name is not nearly so well known as theirs. This is largely to do with his having left New York for Europe in 1965, after which he entered a period of what he cheerily described as "accelerated creative inactivity". Starting in Rome, he moved to Villefranche-sur-Mer, near Nice, in 1968, opening a shop called La Cédrille qui sourit ("the cedilla that smiled") with which he hoped to explore "obtuse relationship[s] to the institution of language." This enterprise, not surprisingly, closed after a few months.

In 1971 Brecht moved to Cologne, where he married and lived in relative obscurity for nearly 40 years. It was only with the renewed interest in Fluxus art at the beginning of this decade that his name began to appear once more in the pages of art magazines. In 2005, the Museum Ludwig in Cologne staged a one-man show, dubbed a "heterospective" of Brecht's work. It later transferred to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona but no US venue could be found to take it; an omission which Artforum magazine described as "putting America to shame".

Charles Darwent

George Ellis MacDiarmid (George Brecht), composer and artist: born New York 27 August 1926; married (one son); died Cologne, Germany 5 December 2008.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies