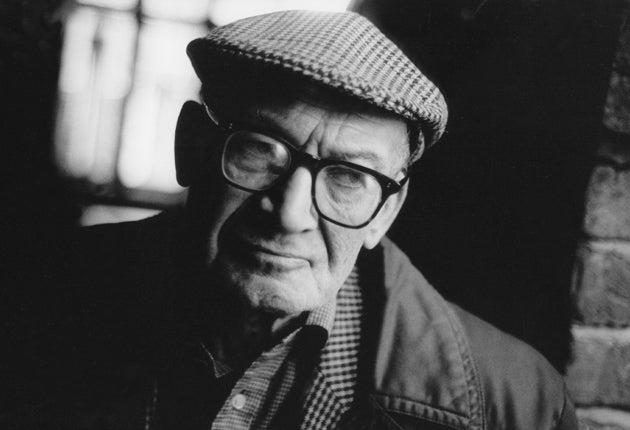

Harry Diamond: Photographer and eccentric denizen of post-war Soho

Harry Diamond achieved a degree of fame in his forties, when some of his photographic portraits were acquired by the National Portrait Gallery, and Lucian Freud's paintings of him were widely shown. Yet he was an omnipresent figure to several generations of Soho habitués, musicians and painters, long before that. Inevitably, when Frank Norman's 1959 book about Soho, Stand on Me, was published, it was Harry Diamond who was pictured talking to him on Herb Greer's classic cover.

Harry knew everybody in the Soho of the time and it was something of a paradox that everybody knew him, was fond of him, and yet tended to avoid him. He was a frustrated and abrasive character, an Ancient Mariner, much given to immobilising people for long periods while he harangued them on the iniquities of governments, officialdom or the politics of Soho jazz clubs.

He was born in South-east London in 1924 to a trading family (his father was a successful tailor) who were by the standards of the time, relatively comfortable. He left home at 14, and his life between then and his appearance in early-Fifties Soho remains a complete blank. He never discussed these missing years with anyone. Somehow, by 1950, he had acquired a thick, frequently impenetrable accent that, as the guitarist Pete Emery said, "sounded as if he had just got off the boat from Russia".

Why he constructed this working-class ethnic persona remains a mystery. He was volubly anti-racist, with little time for those he regarded as "professionally Jewish". Right at the end of his life, knowing he had to enter a nursing home, he refused to go to a Jewish establishment on the grounds that it was a form of segregation.

He was for many years a stage-hand, switching between the Palladium and Covent Garden. During lay-offs he worked on the street bookstall I ran in the evenings outside Foyle's. Sales tended to slump a bit during Harry's tenure. I would sometimes return to the stall to find him ignoring paying customers while earnestly spluttering out improbable tales of Soho low-life to Colin MacInnes or Laurie Taylor. It was Harry who first cashed a cheque for MacInnes, who said in a column somewhere that the stall was the only place where you could cash a cheque at midnight. As a result the stall tended to be beseiged around that time by dubious characters with even more dubious cheque-books, seeking financial aid.

Later I offered Harry the stock and barrow for the daytime stall I had off Cambridge circus, where Bernie Kops also held court. One day, after a bad week, he tipped all the stock on to a waste site, pushed the barrow on top of it and walked away; a typically impulsive action. He moved on to other Soho jobs, for a while becoming a sort of "character-in-residence" at Ronnie Scott's. During this period Scott went to the palace to collect his OBE. On his return his partner Pete King asked how the event had gone and added: "Did she ask about Harry Diamond?"

Eventually, though, he returned to his primary work as a stage-hand, now at the Palladium. Contact with the stage photographer Michael Peto gave him an interest in photography that he developed with the same manic intensity which he brought to jazz and his particular version of jazz-dancing. The latter was an astonishing spectacle, seemingly anticipating break-dancing in Britain by several years.

In photography, both portraits and street scenes, he found his true metier, creating famous portraits of Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon and Eduardo Paolozzi among many. In Freud's case at least, he was returning a favour, as Diamond had sat for Freud as early as 1951. This was for the painting Interior at Paddington, part of an Arts Council Festival of Britain commission. The architect John Lapthorne, who had known Diamond in his own Soho days as a student, tells of his astonishment when wandering round the Museum of Modern Art in New York on suddenly being confronted with a life-size Harry Diamond on the wall.

The National Portrait Gallery picked up a number of Diamond's portraits and he returned that gesture by leaving the bulk of his unsold work, his camera and working tools to the NPG. For a while his work was fashionable, but difficulties in persuading him to exhibit led to a loss of interest and when I last met him in the Wenlock, a pub off City Road, listening to the ex-Humphrey Lyttelton pianist Johnny Parker, he told me he was finished with photography as there was no money in it.

Neither part of this comment was strictly true, perhaps, but he certainly fell out of the public eye – although he could still be found in the specialist jazz-record shops most Saturday afternoons and was not obviously impecunious.

His funeral took place on 23 December 2009. It is perhaps typical of the affection with which the jazz world regarded him that one of Britain's premier saxophonists, Alan Barnes, rose at 7am in order to play at his funeral. He was possibly the last of the great Soho eccentrics from a time that also numbered Jeffrey Bernard, Sidney Knight, Ironfoot Jack and George Melly. He was a difficult man, but many will miss him and mourn the loss of this autodidact talent.

John Pilgrim

Harry Diamond, photographer: born London 25 August 1924; died London 3 December 2009.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies