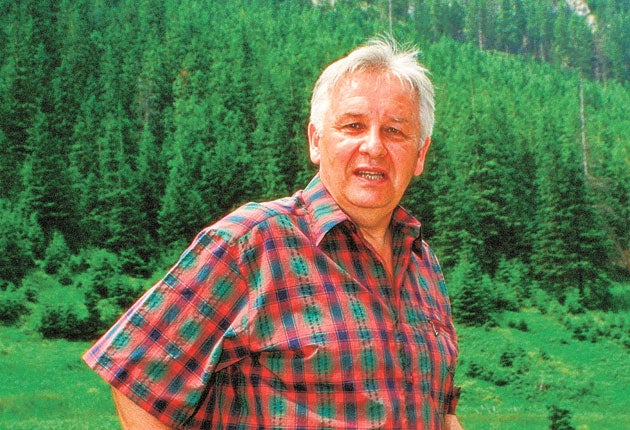

Henryk Gorecki: Modernist composer who enjoyed crossover success with the million-selling 'Symphony of Sorrowful Songs'

In Britain, Henryk Gorecki was best-known – to some, only known – as the composer of his meteorically successful Third Symphony (the "Symphony of Sorrowful Songs").

Yet for years he was a quiet pathbreaker in Polish new music, and commercial success scarcely changed that.

Henryk Mikolaj Gorecki was born in December 1933 in Czernica, close to the Polish border with Czechoslovakia. "My grandfather died in Dachau," he recounted, "my aunt in Auschwitz, which was close to where we lived, and my uncle in another camp."

Young Gorecki suffered tuberculosis and then a dislocated hip, undergoing hip surgery and subsequently passing two years in a home for disabled children. "Surgeon's knife and plaster, from one hospital to another, are my recollections," as he put it.

After the war, the teenaged Gorecki began instrumental lessons, and studied music in evening classes at Rybnik's Intermediate School of Music, while working as a primary schoolteacher. Just before his 22nd birthday he won a scholarship to the Katowice State Higher School of Music, where he studied composition with Boleslaw Szabelski, a former student of Karol Szymanowski.

Epitafium (1958) was the first of almost 30 of Gorecki's pieces to receive a premiere at the Warsaw Autumn festival, which from its inception in 1956 was "an annual symbol of resistance to the Soviet system". Gorecki recalled: "I remember these times with pleasure because they were a great reawakening for Polish music. I don't know how we got away with it year after year."

During his studies in Katowice, Gorecki met a piano student, Jadwiga Ruranska. In July 1959, a year before he matriculated, they married; their daughter Anna was born in 1967, their son Mikola in 1971.

Gorecki's First Symphony (1959) symbolised a new start for Poland and in his own life. Although later he considered it a student exercise, it took that year's Warsaw Autumn by storm. Scontri succeeded likewise the following year, its use of sound-mass prefiguring the '60s orchestral sound of Polish music for which Penderecki became better-known, while Monologhi for soprano and three instrumental groups was awarded first prize in a competition sponsored by the Polish Composer's Union.

Gorecki wanted to use his prize money to exploit the cultural thaw between Eastern and Western Europe at the end of the 1950s. His first thought was to study with Luigi Nono, but instead he went to Paris, where he renewed contact with Pierre Boulez and met Karlheinz Stockhausen. He also encountered Olivier Messiaen, though he never studied with him, despite many accounts to that effect.

Gorecki related, perhaps with some poetic licence, that someone said he could not write tuneful music, and to prove them wrong he composed Three Pieces in Old Style (1963), with whole-tone harmonies and modal melodies including, in the last movement, a reworking of a 16th-century Polish song. His own emerging voice, then, was intertwined with the deepest-lying of his influences. "Folk music is everything," he once declared. It seemed like a recipe for greater popularity, but in the "serious" music circles in which he moved, his new turn was heretical. Ironically, Gorecki observed, "that was avant-garde when I started composing in this manner".

Unesco declared 1973 "Copernicus year", and Gorecki was commissioned to write a commemorative symphony. From 1973 to 1974 he was awardeda German Academic Exchange Service fellowship which took him to Berlin, but his stay was cut short by serious illness. On the whole his career at this time was limited to Poland. In 1975 he was appointed rector of his old school in Katowice, and in 1977 he became a professor at the State Higher School there.

Back in the 1960s, Gorecki hadconceived a tribute to the victims of Auschwitz, thinking, too, of hisrelatives who had perished there. "This composition has been gathering in my mind for years," he said in 1968. "It frightens me and is compellingly attractive at the same time. As soonas I was asked to perform it at a memorial service in the camp, I stopped work."

Towards the end of 1976, Gorecki continued the piece in a new guise. The germ was his discovery of a folk song from Opole. "It came to my mind to write some similar songs for soprano and orchestra," he remembered. "It was quite difficult to fit anything with this song, because it's about a mother crying over her son."

In a book on the Nazi occupation, he discovered words found scratched on a wall in the Gestapo prison at Zakopane: "No, mother do not weep...", signed by "Helena Wanda Blazusiak, aged 18, detained since 25.IX.44." To this he added a text from the 15th-century, "Holy Cross Lament". "So I had these three songs, very sad, hence the title 'Symphony of Sorrowful Songs'."

These were volatile times in Poland. "When the war ended it merely meant a change of masters," Gorecki once observed, and the late 1970s marked the rise of Solidarity and other movements against Soviet domination. Karol Wojtyla – before he became Pope John Paul II – had commissioned a Beatus Vir from Gorecki. When the composer conducted his work in the presence of the Pontiff, as he by then was, he was quickly forced to resign from his school.

"Too much politics," he reflected. "If I hadn't resigned I really think they might have killed me. I was treated as though I was dead. My name was removed from the records. My students weren't allowed to say they had studied with me."

Despite further serious illness in 1984-85, the '80s marked Gorecki's full emergence on to the international scene. His Harpsichord Concerto (1980) was trailblazed in the West by the flamboyant Polish expatriate, Elisabeth Chojnacka, and the pop stars of the chamber music world, the Kronos Quartet, commissioned Already it is dusk (1988).

When David Zinman and theLondon Sinfonietta made a new recording of the Third Symphony with the soprano Dawn Upshaw, thepromoters thought it was a typical new-music turkey. In the first weekof 1993, however, it hit No 1 in theclassical charts. Compared to most classical symphony releases, which average 10,000 sales, the Gorecki sold a million that year – 14,000 on one single day in Britain.

Its success pleased yet puzzled him. No one, he observed, could explain why this piece had been successful at this time. "Perhaps people, especially young people, find something they need in this piece of music, something they are seeking. I am simply glad that people outside the world of classical music have been buying it." He added mischievously: "If they are buying my disc rather than cigarettes, I am saving lives all the time."

Engagingly, the most he could think of doing was to buy a secluded cottage in the Tatra mountains where he could proceed with his work. "What do people want from me?" he asked. "I am an old man, not a star like Woody Allen or Michael Jackson. I am happy to be left alone with my Tatra mountains, my piano, a piece of paper and a pen. A day away from Katowice, where I write, is a day wasted."

Henryk Mikolaj Gorecki, composer: born Czernica, Poland 6 December 1933; married 1959 Jadwiga Ruranska (one daughter, one son); died Katowice, Poland 12 November 2010.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies