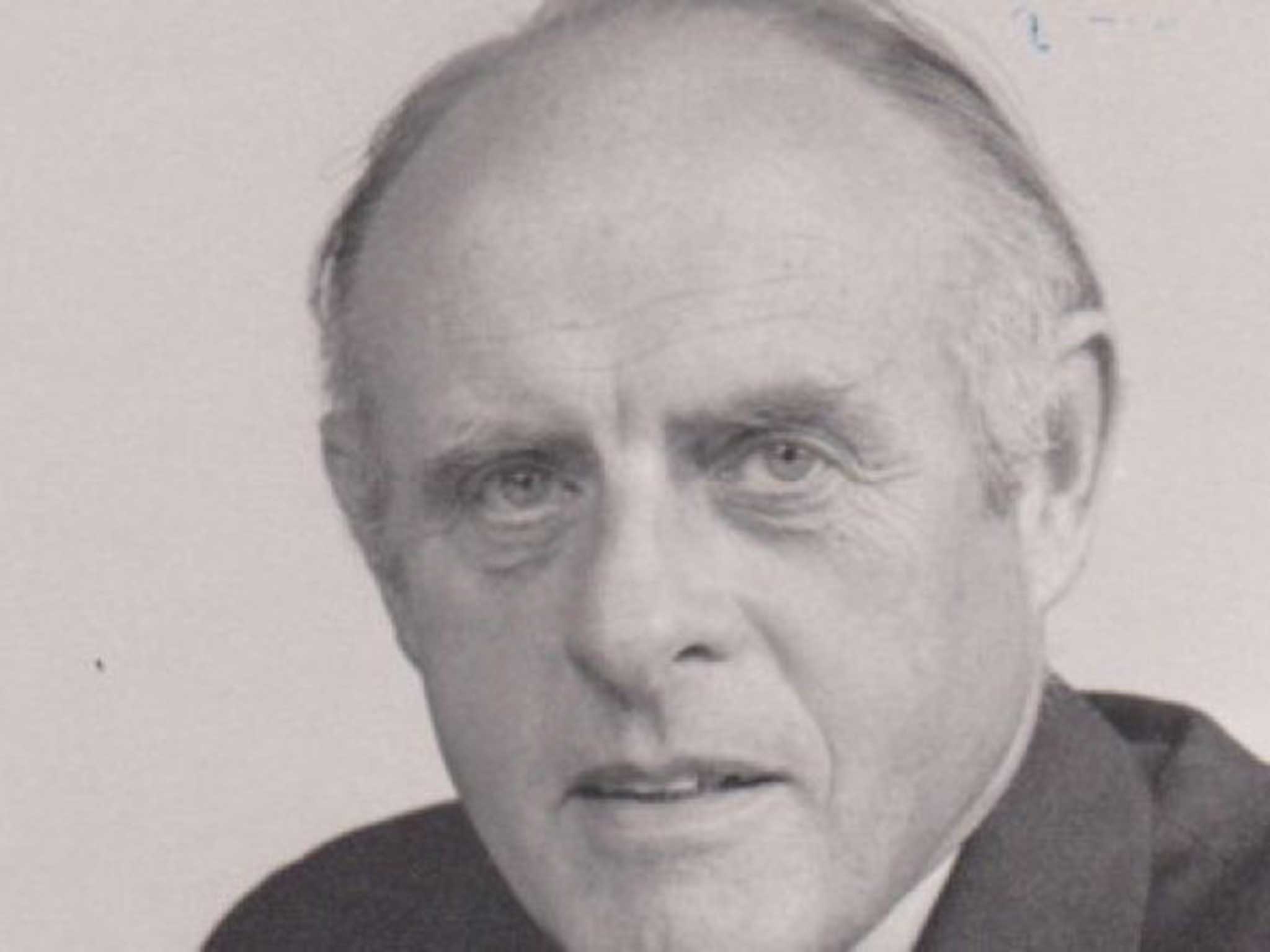

John Martin Fearn: One of the last members of the 'heaven-born' elite of the Indian Civil Service in the run-up to independence

John Martin Fearn was one of the last of the Indian Civil Service elite, the “heaven-born” 800 or 900 men who at any one time governed 250 million people in British imperial India.

War, shipwreck, earthquake, and swirling dust were his lot, but his greatest trial was the call upon him of his superior, the eccentric Sir Penderel Moon, Deputy Commissioner at Amritsar, to play the piano to Moon’s recital of classical German Lieder.

In his probationary year in 1939 at Worcester College, Oxford, Fearn had learned the Urdu language, the Indian Penal Code and horsemanship, but the musical instrument to which he was led in Moon’s well-appointed bungalow two years later defeated him.

The son of a house-furnishing businessman from Wormit, Dundee, he was educated at Dundee High School and won a scholarship to St Andrews University, where he took a First in Economics and History, graduating MA. He won his job by doing well in a stiff competitive examination and set off from Britain for Bombay in September 1940, only for his steamer, the SS City of Simla, to be torpedoed a few hours out of Gourock, off the west coast of Scotland, by U-boat U-138.

The ship stayed afloat for some time, lights blazing, before sinking, and most of the passengers were taken to Londonderry in Northern Ireland, with three lives lost. Within weeks Fearn continued the 14,000-mile journey – not, as in peace time, through the Suez Canal, but all the way round the Cape of Good Hope, just as in the 18th century his East India Company predecessors had been obliged to do.

His first posting was to Multan, now in Pakistan, where he attended court hearings and went on tour. He stayed at Kasauli, now in Himachal Pradesh, India; and then at Gurgaon, now in Haryana, India. Resolving disputes he applied legal procedures devised by his service forebears Thomason and Prinsep 100 years before. There followed a year’s training at Amritsar, staying as a paying guest with Moon, and sitting, inexperienced as he was, as a magistrate with power to commit cases of murder. Moon includes a sketch of Fearn as – in Fearn’s words – “a very green young magistrate” in his book Strangers in India (1944).

Fearn next joined the provincial secretariat in Lahore, and wrote of the work: “My headaches were molasses and coal.” The headaches ended with his appointment as sub-divisional officer at Kasur, 30 miles south on the Ferozepur road, and covering a third of the Lahore District. Here a visiting judge, PM Hubbard, who disliked the “startling smells” of the town, wrote of him: “The SDO who’s always here / Grows hardened to the atmosphere” whereas “the wandering judge who comes on session... cannot face another day, but hangs his man and gets away”.

Fearn was the only resident European in the area apart from the local superintendent of police. Part of his job was to appoint village headmen. He had no wireless nor running water, nor a refrigerator, and in the hot weather of 1945 had to flee his house, an old building with a heavy dome under which he slept, when an earth tremor criss-crossed it with cracks.

His duties included riding across country to three or four villages each day, and every evening reading the “office dak” (post), only stopping when his laboriously pumped-up pressure lamp expired. For leisure he played tennis with Adam or went on a partridge shoot, and at weekends escaped to Lahore’s Punjab Club, where war rations were three chhota-pegs (small measures of whisky) a night.

Promotion came through death: the departing Lahore Deputy Commissioner’s successor-designate sickened and in March 1946 breathed his last, and Fearn, then aged 29, was summoned to fill the void. He found himself in charge of a city seething with political intrigue and discontent. Lahore had a military cantonment nearby and Punjabis feared a spill-over of the violence that in August 1946 killed thousands in Bengal. A reformed government, with Sikh, Hindu and Muslim elected ministers, was not working, and the deputy commissioner remained the hearer of choice before whom people wished to lay their grievances. There was, Fearn wrote, “unremitting tension”.

Amid it all he performed, almost every week at least one civil marriage, a service much in demand by European and Anglo-Indian couples. Protests were a daily event, but emerging habit mitigated even these. Police and demonstrators would agree each time how many arrests should be made – say 20 or 30 – to satisfy the honour of both sides, and then everyone would go home. Once, when a brick from a crumbling wall fell and killed a Muslim man by accident as a demonstration was taking place, protesters accorded the victim a martyr’s funeral. Almost the last public duty Fearn performed was to attend the ceremony with a duly large force of police.

The length of the Second World War meant that home leave was, after six and a half years’ service, long overdue for Fearn, and he sailed for Britain in March 1947 with Indian independence and partition less than five months away.

Britain’s shrinking world role shrank his job, too: newly married, he opted for the Scottish Home and Health Department, part of the Scottish Office, at St Andrew’s House in Edinburgh. There, as an assistant principal, he devoted the many skills learned from 200 years of Britain’s far-flung rule, to a microcosm: Scotland’s hospitals, health services, prisons and courts. His wisdom was listened to when he advised that introducing legislation in Scotland aimed at controlling the 1960s flush of sexually explicit theatre performances – abhorred by the country’s Presbyterian Kirk – might bring Scotland’s distinctive legal principles “under hostile scrutiny”.

In 1968 he switched to education, becoming under-secretary, and in 1973 took over as secretary, with responsibility for schools and universities. He was appointed CB on his retirement in 1976. His assessment for the ICS notes his “happy blend of seriousness and humour” and considers him “self-reliant without a trace of conceit” , as well as “naturally sympathetic and considerate of others.” He never returned to India.

John Martin Fearn, civil servant: born Dundee 24 June 1916; CB 1976; married 1947 Isobel Mary Begbie (died 2006; one daughter); died Edinburgh 18 October 2014.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies