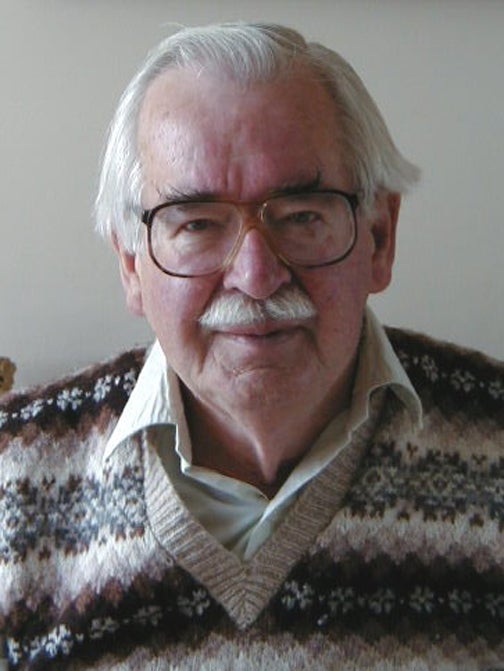

John Rowe Townsend: Editor and prolific author who championed children’s literature and became a leading figure in its postwar revival

The author of 36 books, John Rowe Townsend was a leading figure in the postwar revival of children’s literature. He was also children’s books editor for The Guardian and set up that paper’s Children’s Fiction Prize in 1967, writing authoritatively about children’s literature while remaining a popular author in his own right. Never afraid to enter into controversies, he was for many years one of children’s literature’s best-known ambassadors.

Born in Leeds in 1922, Townsend produced his first unpublished novel aged eight. An otherwise settled childhood was blighted by poverty after his father, chief clerk to the Yorkshire Copper Works, retired on a small pension after contracting Parkinson’s disease.

Winning a scholarship to Leeds Grammar School, Townsend did well but still had to leave at 17 for a job with the Inland Revenue. Three years later he joined the RAF. Making use of a prolonged and inactive stationing in Florence in 1944 he started what he later termed as his real education in art and literature, learning Italian and getting to know every square and statue. In 1945 he married Vera Lancaster and the next year talked his way into Emmanuel College, Cambridge for a degree in English. Time spent working on Varsity, the student newspaper, led to a job with the Manchester Guardian for the next 20 years.

Reviewing children’s books, with their habitual middle-class bias, he decided it was time for something different. Drawing on his childhood experience and recent research for an article which involved accompanying NSPCC inspectors on their rounds, he wrote Gumble’s Yard (1961). An immediate and long-lasting success, it describes how two slum orphans temporarily abandoned by their feckless alcoholic uncle still manage to fend for themselves.

More realistic in its setting than in its plot and characters, with its hero, 13-year-old Kevin, speaking impeccable English throughout, it was still revolutionary for its time in its unswerving depiction of grim living conditions. It was later successfully televised. His second novel, Hell’s Edge (1963), describes the difficult journey of understanding made by a girl from a superior private school when she is thrown together with a rough Northern working class boy.

Two years later Townsend produced Written for Children: An Outline of English Children’s Literature (1965). Based on a series of lectures he gave at Manchester and Sheffield universities, this readable and scholarly history filled a gap in the growing market for books about all aspects of children’s literature. It went on to nine further editions.

By now encouraged by his wife and three children to become a full-time writer, he left The Guardian in 1969, though staying on as children’s books editor until 1978. Teaching at American universities followed, along with another critical work, A Sense of Story: Essays on Contemporary Writers for Children ((1971). This, too, was well received, with an extensively revised edition, A Sounding of Storytellers, appearing in 1979.

More novels also followed, now aimed at a young adult audience. The Intruder (1969) is a powerful and strikingly original description of a teenager’s struggle to hold on to his own identity. A runner-up for that year’s Carnegie Medal, it was followed by Good Night, Prof, Love (1970) where a shy adolescent boy falls in love with a woman both older and more experienced. Sensitively written, this story once again successfully challenged still existing taboos in children’s literature and was widely praised.

In 1973 his beloved wife Vera died following a long illness, leaving Townsend with three school-age children to bring up. But a move to Cambridge from his previous home in Knutsford, near Manchester, led to a new relationship, with Jill Paton Walsh, another distinguished children’s writer. Sharing a country cottage in the riverside village of Hemingford Grey, the couple worked harmoniously at separate desks in the same large room. There were also more joint visits to work in universities in America, Canada, Australia and Japan plus the purchase of a 60-foot canal boat in 1975. Enjoying their mutually rewarding partnership, they eventually married in 2004.

In 1994 Townsend wrote his last book, Trade and Plumb-Cake for Ever, Huzza!, a celebration of the life and works of John Newbery, the pioneering 18th century publisher of children’s books. Still busy, he and his wife founded their own publishing company, Green Bay Publications. They also organised annual conferences and were hosts to many visitors from abroad, with the canal boat playing a full role in the general hospitality.

Temperamentally reserved and sometimes prickly, particularly when he felt patronised by those who thought that children’s literature was an altogether less serious enterprise than its adult counterpart, Townsend lived to see his life-time commitment to this subject endorsed by growing numbers of university courses at home and abroad. His own contribution here remains an outstanding one, both as writer and critic. He is survived by his wife, his two daughters, Thea and Penny, and seven grandchildren. His son Nicholas predeceased him.

John Rowe Townsend, journalist, critic and writer: born Leeds 19 May 1922; married 1954 Vera Lancaster (two daughters, and one son deceased); died Cambridge 24 March 2014.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies