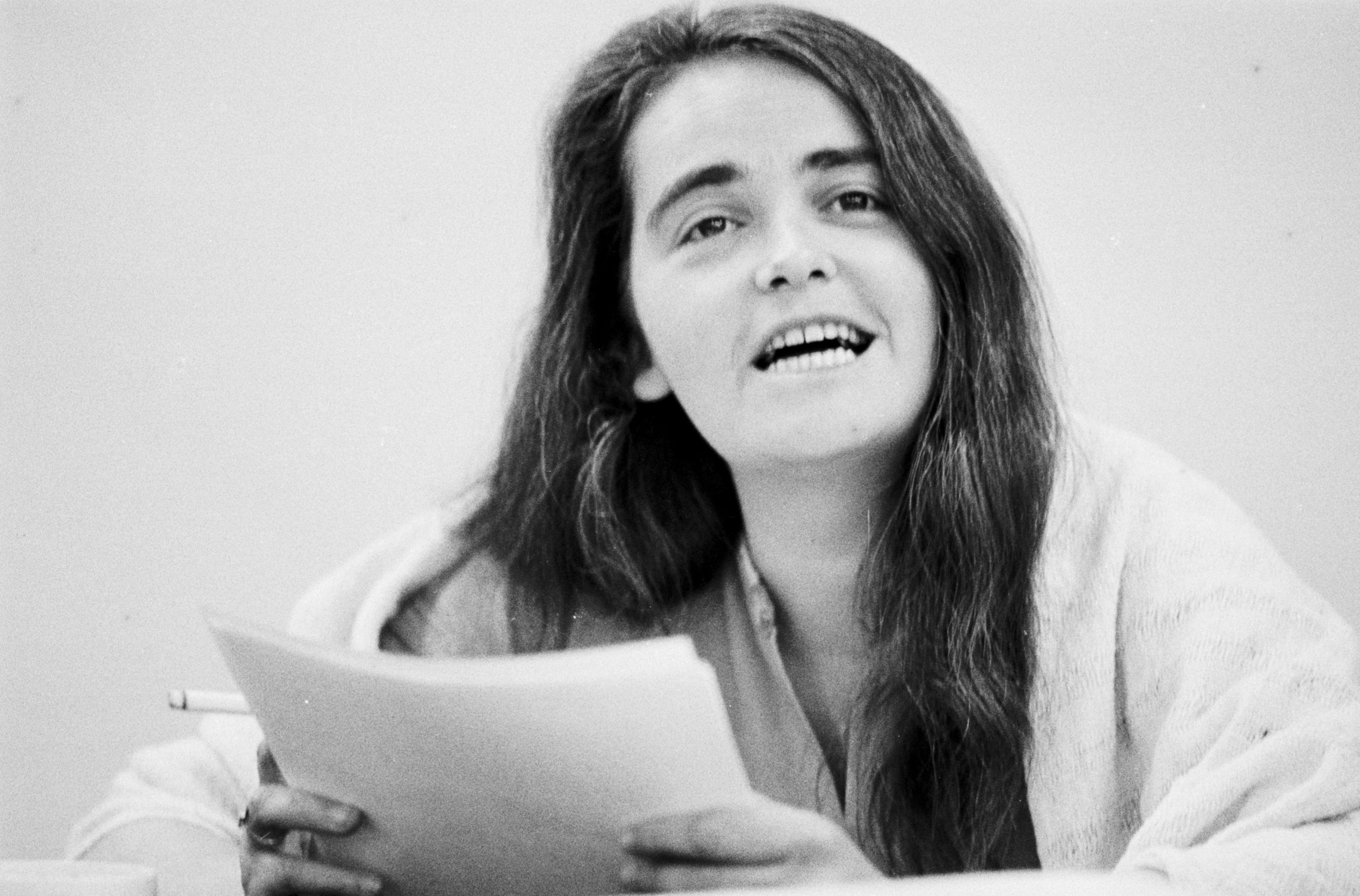

Kate Millett, second-wave feminist who wrote about cruelty and injustice

The ‘high priestess’ of women’s liberation campaigned for all the disadvantaged, after suffering a long period of mental illness

Kate Millett was a feminist writer and artist who gave the women’s liberation movement its intellectual cornerstone with the 1970 tract Sexual Politics, and whose later works laid bare the subjugation of gay people, the mentally ill, the elderly and victims of political oppression.

Millett, who has died aged 82 in Paris, was a contemporary of Gloria Steinem’s – the Ms magazine co-founder was six months her senior – and along with Steinem became a driving force behind feminism’s “second wave”, which transformed the movement in the 1960s and 1970s.

Second-wave activists, who also included Betty Friedan, sought to advance the concept of women’s rights beyond voting and other legal privileges, to include workplace equality, marital equality and greater sexual freedom. Sexual Politics, Millett’s debut book, emerged from her doctoral thesis at Columbia University.

It posited that “every avenue of power within the society, including the coercive force of the police, is entirely in male hands,” and that “as the essence of politics is power, such realisation cannot fail to carry impact”.

She traced the patriarchy from biblical presentations of women to Sigmund Freud’s concept of “penis envy”, to inequitable marital arrangements that persisted even after the women’s movement took hold. “She opened up the eyes and the minds of women to the possibilities of freedom, the urgency of freedom and the fact that terrible things happen to women” – things “that few could look at [as] closely as she did,” said feminist writer Phyllis Chesler.

Millett’s book vaulted her to national renown. Time magazine featured her portrait on the cover of its edition of 31 August 1970. The New York Times described her at the time as the “high priestess of the current feminist wave,” with book critic Christopher Lehmann-Haupt lauding Sexual Politics as “written with such fierce intensity that all vestiges of male chauvinism ought by rights to melt and drip away like so much fat in the flame of a blowtorch”.

But the attention also proved burdensome for Millett. In 1970, while married to a Japanese sculptor, she was speaking at Columbia when an audience member demanded to know if Millett was a lesbian. “Five hundred people looking at me,” Millett later wrote. “Everything pauses, faces look up in terrible silence. I hear them not breathe. That word in public, the word I waited half a lifetime to hear. Finally I am accused. ‘Say it. Say you are a lesbian.’ Yes I said. Yes. Because I know what she means. The line goes, inflexible as a fascist edict, that bisexuality is a cop-out. Yes I said, yes I am a lesbian. It was the last strength I had.”

In her memoir Flying (1974), she recounted the emotional upheaval of the fame Sexual Politics had brought her – it “grew tedious,” she wrote, “an indignity”. Her next volume, Sita (1977), chronicled her affair with a woman amid Millett’s fracturing marriage – she was ultimately divorced from her husband, Fumio Yoshimura – and her struggles with mental illness.

During the 1970s, she was institutionalised for the treatment of bipolar disorder. She recalled those experiences in her book The Loony-Bin Trip, published in 1990. “Not since Ken Kesey’s ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’ has the literature of madness emitted such a powerful anti-institutional cry,” the feminist writer Marilyn Yalom observed in a Washington Post review.

And the experience of being institutionalised seemed to heighten Millett’s sensitivity to the suffering of others. Her books on that theme included The Basement (1979), the true story of the prolonged torture and murder of a young girl, Sylvia Likens, in Indiana in 1965.

Millett undertook what she described as a “mission to and for my sisters in Iran,” travelling to the country for International Women’s Day in 1979 and finding herself arrested, and then released, by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in an episode she detailed in Going to Iran (1982).

Her book The Politics of Cruelty (1994) explored abuses in the Soviet Union, Nazi Europe, Ireland, South Africa and beyond. Chesler described Millett as “very sensitive to the violence done to women” that others “didn’t think we could ever name or didn’t think ... could ever change”.

Katherine Murray Millett was born in St Paul, Minnesota, on 14 September 1934. Beside her second spouse, Sophie Keir, a list of survivors was not immediately available. Millett’s father was described as an abusive alcoholic and abandoned the family when Millett was in her teens, leaving his wife to support their children.

When her elderly mother was forced to enter a nursing home, Millett was repulsed by similarities between that facility and the mental institutions where she had been placed. She helped arrange for her mother to be cared for at home, an experience she recounted in the book Mother Millett (2001).

Millett received a bachelor’s degree in English from the University of Minnesota in 1956 and, while supported by a wealthy aunt, a degree in English literature from St Hilda’s College at the University of Oxford in 1958. With Sexual Politics, she received a PhD in English and comparative literature from Columbia in 1970.

She worked as a sculptor and taught at universities including Barnard College in New York City, Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania and the University of California at Berkeley. She joined the National Organisation for Women shortly after its founding in 1966, and chaired its education committee.

In 1971, she filmed the documentary Three Lives, made by an all-female team. She later founded a women’s art colony, Millett Farm, in Poughkeepsie, New York, running the operation into her later years.

For all she did to awaken women to the ancient inequities that they shouldered, Millett recognised that change would come only at an agonisingly slow pace. She likened sexism to racism. “You can legislate about it, but as long as everybody is racist, you don’t really do much about it,” she told The Washington Post in 1970. “Unless you change persons and attitudes, you haven’t changed much.”

Katherine Murray Millett, second-wave feminist, born 14 September 1934, died 6 September 2017

© Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies