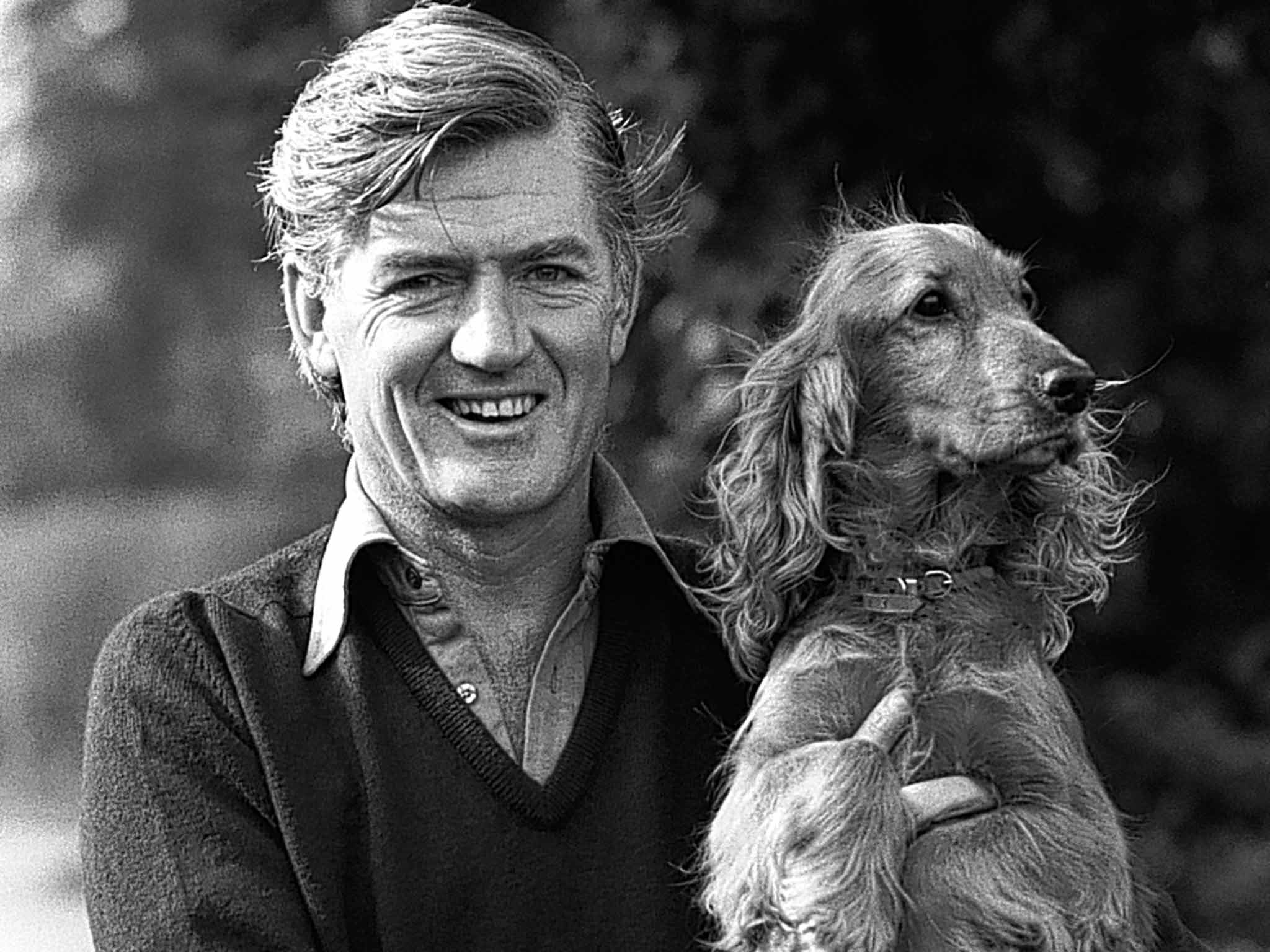

Lord Parkinson: Thatcher favourite who served as Tory Chairman and Energy Minister but was laid low by scandal

For a man with a laminated manner and reasonably secure posh accent, Parkinson came from the plainest of northern working class backgrounds

The career of Cecil Parkinson was an instance of the ruinous power of publicity. Spotted in the 1970s by astute commentators as both serious talent and the sort of man likely to climb high in the sky if Margaret Thatcher were the sun shining in it, he performed up to expectations until one day in October 1983 when, for reasons of good old-fashioned sex, he fell out of it.

The pregnancy of Sara Keays would have made a good bad novel. It was many clichés packed together: the bringing down of the mighty from their seat, (more interestingly, the dishevelment of a smooth man), the baby on the doorstep and, of course, the woman scorned. It was banal and it was a thousand acres of newsprint, interesting to their readers in ways which the privatisation of electricity – Parkinson's later and rather important ministerial responsibility – never quite managed.

For a man with a laminated manner and reasonably secure posh accent, Parkinson came from the plainest of northern working class backgrounds. His father, Sydney, was a railway plate-layer, his mother, Bridget, Irish Catholic. Home was Carnforth at the top end of Lancashire, and as a sixth former the young Cecil was a Labour supporter. He liked the arts and at Emmanuel, Cambridge, read English under Leavis before switching to Law. He was also a running blue. Bright, hard working, ambitious, always very likeable to those who knew him, he was drawn to the business world, going into partnership with Billy Hart, concentrating firstly on that.

The move to the Conservative Party, then active politics, followed at an easier pace. He made a marriage within the business world to Ann Jarvis, whose father was a major figure in civil engineering and construction, and moved to Hertfordshire. There was too, a political alliance, also in Herts, with a sharp-tongued, prejudiced, brilliant airline pilot called Norman Tebbit, starting at Hemel Hempstead constituency association (Tebbit was vice-chairman to Parkinson's chairman). Over a 25-year partnership, Tebbit would be the rough to be taken with his own smooth. And Tebbit once conceived of a mythical, strengths-combining politician, “Tebbitson”.

Financially secure and comfortable in business, the political Parkinson emerged, narrowly missing Truro, then fighting Northampton in 1970. By a melancholy turn of fortune, almost immediately after defeat he found a neighbourhood seat at Enfield on the historically crucial death of the new Chancellor, Iain Macleod, and entered parliament at 29.

His ascent began after the advent of Thatcher in 1975. She was constrained for a long time as the right-wing protest leader of a party which was distinctly conciliatory and centrist. But opposition is good for rising men; Tebbit and Parkinson were on shortening odds for advancement when her position could be consolidated. A good performance on the budget team and (perfectly sincere) preachings of the Thatcher gospel, were followed by Parkinson's becoming a Trade spokesman. And as he would always say of himself, “What I really am is a first class salesman.”

The trajectory was set for office when in 1979 he became a junior minister at Trade, where he travelled furiously and made some impact. His appointment as Party Chairman in 1981 was part of Thatcher's imposition of her own stamp on the party, and Tebbit, a Minister of state at Industry, came up at the same time.

Although he enjoyed luck, much of it called Michael Foot or the Falklands War, Parkinson was an excellent Chairman. He grasped the importance of the SDP Liberal Alliance – which would in fact, almost overtake Labour in the election – understood at once the relevance of the Alliance setback in the Darlington by-election, and successfully pressed an early election upon an unsure Thatcher. He was sensible, good-tempered and employed the party's strength gracefully.

On election day, with a majority of 100 and the personal admiration of the Prime Minister, he looked like a future Chancellor, Foreign Secretary and serious runner for a properly apostolic premiership. On that same day he told his leader of the pregnancy of his former secretary, Sara Keays, something which came public at an otherwise triumphant Conservative conference. It was never bright, confident morning again.

Thatcher, as well as valuing and liking him, was utterly unpuritanical about matters sexual. Left to herself she would have strolled through the hoo-ha and given her favoured colleague the promotion she intended. Parkinson had made his decision in favour of staying with his wife. But despite such submission to the family values they proclaimed, neither his colleagues, led by a quietly contented William Whitelaw, nor the tabloid press, would permit such a liberal (and French) course. Neither would Keays.

The issue took Parkinson out of the Cabinet for some years, and conflict over the child's settlement bubbled up, recurring across the decade. Keays accused him of telling her secrets during the Falklands war, something referred to the DPP. The issue also led to a break-up with Tebbit, advancing as Parkinson stumbled.

Parkinson would come back eventually, but as was said of Sherlock Holmes after the Reichenbach Falls, he was never quite the same man. He sat out the parliament in which he had expected to serve in one of the great offices of state, making occasional interventions and working his passage back. After the 1987 election he became Secretary for Energy. It was a complex brief, affording opportunities for privatisation, in which Parkinson believed and for which he would derive support from his own right wing.

Initially he did well, certainly politically, the reception at two successive Tory conferences showing him to be still yearned for in outer party circles. But the question of nuclear power made difficulties; he was advised by expert opinion against privatising it. He also came up against the formidable opposition of Lord Marshall of the Central Electricity Generating Board, but finally had it approved by cabinet.

Essentially Parkinson favoured nuclear power, and his move towards the privatisation of coal fulfilled expectations, often denied, that it was a form of run-down. But actually, doing the full deed, including nuclear power, when he was being accused by CEGB of losing them business and profits, made the operation ever trickier. The costs were higher than ever envisaged and successor companies were not minded to pay it. Accordingly at the very end of his time at Energy, he suffered the clear humiliation of having to withdraw nine Magnox nuclear stations from the privatisation plan. As they produced two-thirds of Britain's nuclear energy, this was a painful public climbdown. And as the costs were by this device shifted to the taxpayer, applause was muted.

All this time he had been thought capable of moving to better things, and he had reputable friends, notably John Biffen, who pushed him as a successor to Nigel Lawson at the Treasury. But though electricity privatisation would work long-term, its achievement was messy, and made for negative politics.

Shares in Parkinson's return slipped badly and in 1989 he was sent not to a great office, but Transport – under the Tories, a despised backwater. And part of that contempt took the form of a Treasury denial of funds, though as Parkinson's plans included £12 billion of road expansion, the parsimony was not everywhere condemned. He had the sense to keep railway nationalisation at arms' length, but was constrained to withhold support on the London-to-Folkestone part of the planned Eurorail.

His last sustained political act was to stay loyal to Thatcher to the end. Although privately sceptical about the Poll Tax, he had been her reliable supporter on the issue in Cabinet. But with her fall in November 1990, he acknowledged the end of his own career and resigned. Giving up his seat at the 1992 election, he became Lord Parkinson of Carnforth, but apart from an enjoyable apologia, Right at the Centre, he played no further part in politics other than a brief return as Party Chairman under William Hague in 1997-98.

Cecil Parkinson was an intelligent, good-natured, pleasant man, good to know, easy to talk to, his private negligence and ill-luck compounded by hesitation in his later posts. But chiefly, he was the victim of rising too suddenly. He behaved well on the way up, but the enemies inevitably assembled on that ascent were waiting when he fell; and the merciless press kicked out of him the old self-confidence so that he came back limping.

But the image is wrong. He was funnier, ruder, lighter-hearted in private than the artifice of his public manner suggested. Oddly, in a man professionally bland, that roughness was part of his appeal to Margaret Thatcher.

Cecil Edward Parkinson, politician and company director: born 1 September 1931; cr. 1992 Life Peer, of Carnforth; married 1957 Ann Mary Jarvis (three daughters); one daughter with Sara Keays; died 22 January 2016.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies