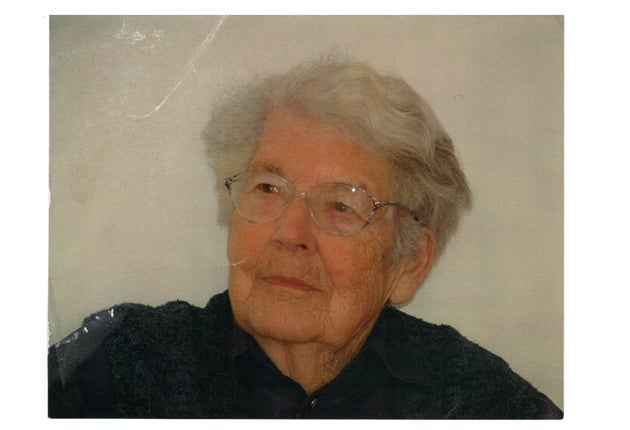

Marian Slingova-Fagan: Political activist who endured solitary confinement in communist Czechoslovakia

Marian Rose Šlingová-Fagan was a political activist who married a Czechoslovakian Communist and found herself caught up in that country's repressive system.

Marian Wilbraham was born to a well-to-do middle-class British family in New Zealand in 1913. Her father died when she was one and her mother returned with her to Britain to live in Oxford. She was educated at the independent Oxford High School and then Somerville College, Oxford University. She became attracted there to the then fashionable Communist movement. After two years of teaching, in 1937 she became secretary of the British Youth Peace Assembly and helped to organise anti-war demonstrations.

Through her wartime work with refugees she met a Jewish exile and fellow communist from Czechoslovakia, Ota Šling. Their marriage in 1941 cost her her British citizenship. She became "a friendly alien" and a citizen of the non-existent Czechoslovakia. Their son Jan was born in 1943, Karel in 1945. After the war they returned to the newly restored Czechoslovakia, where Ota became the most powerful person in the Brno region, the Party's regional secretary. Šlingová was enthusiastic about the Czechoslovakian people creating "a more just society" and worked on her Czech.

In October 1950 Ota was arrested, tortured until he confessed to the most absurd crimes of treason and espionage, and executed at the end of 1952.

His case formed part of the Stalin-inspired Slánský show trial aimed partly at purging the Czechoslovak Communist leadership of Jews. She was imprisoned a few hours after Ota. Seven-year-old Jan and five-year-old Karel went to an orphanage, where Jan was forced to listen to the live radio relay of his father's trial.

Šlingová was kept mostly in solitary confinement for over two years. She knew nothing about her children and learnt about Ota's execution from her only contact with the world, the interrogator. The prison authorities didn't send on her regular letters to her mother in Britain, who consequently knew about their plight only from the British press and pestering journalists.

She was reunited with her children on her release in 1953. The authorities had prepared a flat for them with no bathroom and a shared outside toilet in the north-eastern Bohemian mountains, and had designated a job for Šlingová as a factory hand. They were forced to change their surname to Vilbr, but the locals knew who they were and were very kind. Her pay would not cover the rent and food for three, so the grocer gave her credit. Local women taught her to cook cheap Czech food, and she would carry wood and pine cones for heating the stove from the forest in a piece of cloth fixed to her back. The local schoolteacher brought them rabbits to breed. The former factory owner's widow, who now worked as a factory hand alongside her former servants, gave them hand-me-down clothes. Even local communists tried to help when nobody was watching.

Šlingová resumed correspondence with her 74-year-old mother, who promptly turned up to stay with them for the next five years. She slept in the kitchen on the settee which she had specially sent on from Britain.

After the first revelation of the Stalinist crimes in the Soviet Union in 1956, the family was allowed to move to Prague and Šlingová to work as a foreign editor in publishing. But the boys were still barred from higher education. Jan, interested in history, no good with his hands and frightened of heights, was made to learn a trade and work on a ladder, testing balconies. Karel was trained to work in the mines, where the noise, against which he was not given sufficient protection, permanently damaged his hearing.

Ota Šling was legally vindicated in 1963. The financial compensation was minuscule and Šlingová received none for her own imprisonment. But the boys were allowed to study. Jan started to study law and Karel graduated in economics. The family re-assumed their original surname and spent every summer with their grandmother, who was back in Britain. Šlingová became a full-time translator. She is renowned for her translations of The Axe by Ludvik Vaculík, Pábitelé by Bohumil Hrabal, and economic publications by Ota Šik. She also published the story of her imprisonment, Truth Will Prevail.

After the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia she returned to Britain for good in 1970. The boys stay in Prague. Fairly soon, Jan was arrested for dissident activities, kept in the same prison in Ruzyne where his parents were in the Fifties and expelled to Britain in 1972. Both Šlingová and Jan were stripped of Czechoslovak citizenship for helping to make dissident publications available in the West in English.

Karel signed Charter 1977, a document fiercely critical of the Czech government, lost his job as an economist and for seven years became a manual worker. He was allowed to emigrate to Britain in January 1984 and the family has been here ever since. Šlingová married Hymie Fagan in the 1970s, joined the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and went to Greenham Common. Her last demonstration was against the war in Iraq in Hyde Park.

Marian Šlingová-Fagan, activist and translator: born New Zealand 5 March 1913; married twice (two sons); died London 22 June 2010.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies