Pamela Vandyke Price embarked upon a career of writing about wine at a time when it was still an unusual thing for a woman to do. "She was the first woman to write seriously about wine in Britain [and] did more than most to popularise wine after the Second World War" says her entry in Jancis Robinson's Oxford Companion to Wine. "She is probably most distinguished as a performer, however, having trained initially as an actress." She was also a woman of strong dislikes; a portion of her last few years was spent drawing up a list of those who were not to be asked to her funeral.

But complementing this was a splendidly robust sense of self-aware humour. As she said more than once in her rather scatty memoirs, Woman of Taste (1990), she knew she could frighten maîtres d'hôtel and junior journalists with one glance of her "beady eye", but I shall always remember those expressive eyes surrounded by laugh-lines. Sensationally good company on the wine trips so necessary to every wine writer's livelihood, she was a repository of frank and funny stories about hosts and fellow guests; and, in an unusually maternal role, the keeper of a portable medicine chest that could cope with most mishaps and minor injuries.

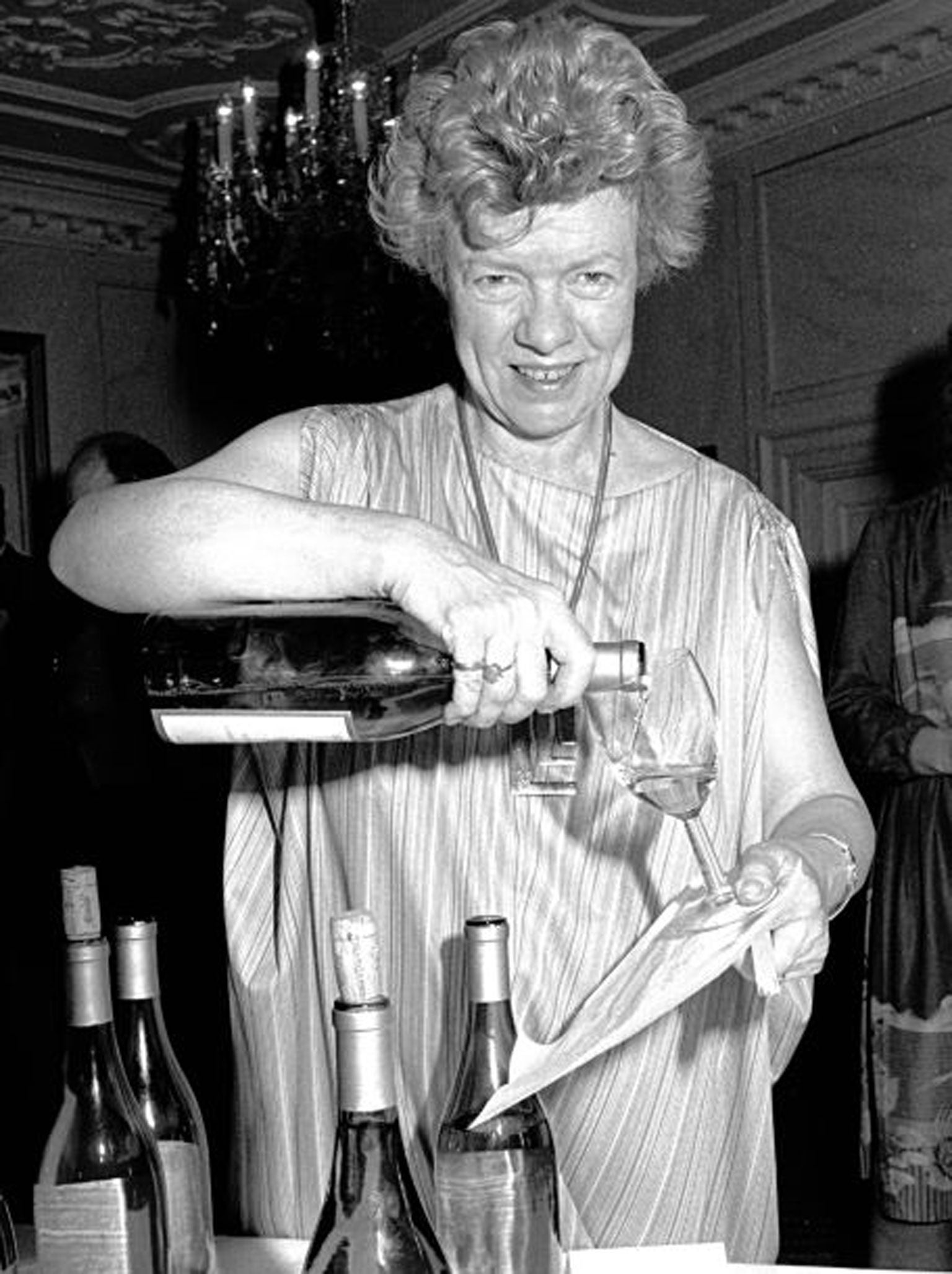

Impatient with younger wine writers' emphasis on the consumer, and the attention they paid to supermarkets and multiple retailers, her mission was to help the trade as a whole. Her introduction to the intricacies of wine-making, tasting and judging its quality, and her understanding of the business of wine came via her mentor, Allan Sichel. She remained a champion of the independent wine-merchant and the traditional structure of the trade. Her ebullient personality made her readers delight in personal contact with her, as in the tastings she hosted as wine correspondent of The Times.

Pamela Walford was born in 1923, the only child of a middle-class Midlands family. Her father was a clock- and watchmaker; when the firm he worked for was bought and moved to London, the family also moved in the mid-1930s. Her Irish-French mother was a secretary; her parents, Pamela wrote, were ill-matched. Educated privately, she read English at Somerville, and was taught by JRR Tolkien and CS Lewis. She got a second, enrolling at war's end at the Central School of Speech and Drama, telling an interviewer in 2001: "I wanted to write plays and produce, but although I can make people laugh I can't make them cry."

Deciding instead to become a journalist, she got a job at Condé Nast as household editor of House & Garden. ("Did they sack me three times," she wondered in print, "or only once?") There, say her memoirs, she "manoeuvred Elizabeth David into working for us. She was impossible but became a very good personal friend." Those who knew both these strong women find this unlikely.

A friend introduced Anglo-Catholic Pamela to medical student Alan Vandyke Price "the scion of two distinguished Jewish families… rising star of his medical group." His mother was Marjorie Vandyke, daughter of SF Vandyke, manager of the Rembrandt Hotel in Knightsbridge. As an 18-year-old Alan was marked by going on a clean-up expedition to Belsen. The couple's common interests were acting and the theatre. He had contracted hepatitis from a patient, and never drank, but "he wished us to be known for our entertaining." In 1955, however, he succumbed to the hepatitis.

Pamela was consoled by a platonic relationship with another, considerably older, Jewish man, Allan Sichel of the Sichel wine company, which owned part of Chateau Palmer. Condé Nast had given her time off to do a Wine and Spirits Association course, so when she met Sichel, and he invited her to accompany him on a buying trip to Burgundy, she didn't have to think long: "I was a pretty piece in those days and thanks to Mummy I always had nice things to wear. So I said to him, 'Why do you want me to go with you'? And he said, 'not, my dear child, for the reason you obviously think. I'm an old man now, my wife doesn't like long drives and I think you'd amuse me'."

She relished the tastings that were the heart of the job, and wrote at least 27 books on wine and food subjects. She won several awards, including a Glennfiddich award for wine writing. In 1981 the French made her a Chevalier de l'Ordre du Mérite Agricole.

She did not scruple to name people who had displeased her, as when she attacked "the astonishing perversity" of her former features editor on The Times. "When a feature was sent back with a furious comment", she wrote in her memoirs, "I would slightly rewrite the first paragraph, and then retype the rest on a different machine. It would always be accepted." In the 1970s she complained to Private Eye: "every time I describe a wine as anything other than red or white, dry or wet, I wind up in Pseud's Corner." She was instrumental in setting up the Circle of Wine Writers and was its sole trustee in perpetuity.

Pamela Joan Walford, wine writer: born Leicester 21 March 1923; married Alan Vandyke Price (died 1955); died London 12 January 2014.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies