Pierre Demalvilain: Schoolboy Resistance fighter who risked his life sketching and recording Nazi defences

Demalvilain became an official member of F2, which provided vital information to the allies from the German invasion of France in June 1940 until after the D-Day landings four years later

As a 14-year-old schoolboy, Pierre Demalvilain was thought to have been the youngest Frenchman to sign up formally for the resistance against the Nazi occupation of his country during the Second World War. Six days before his 15th birthday, and codenamed Jean Moreau, he became an official member of the British-French-Polish resistance network known as F2, which provided vital information to the allies from the German invasion of France in June 1940 until after the D-Day landings four years later.

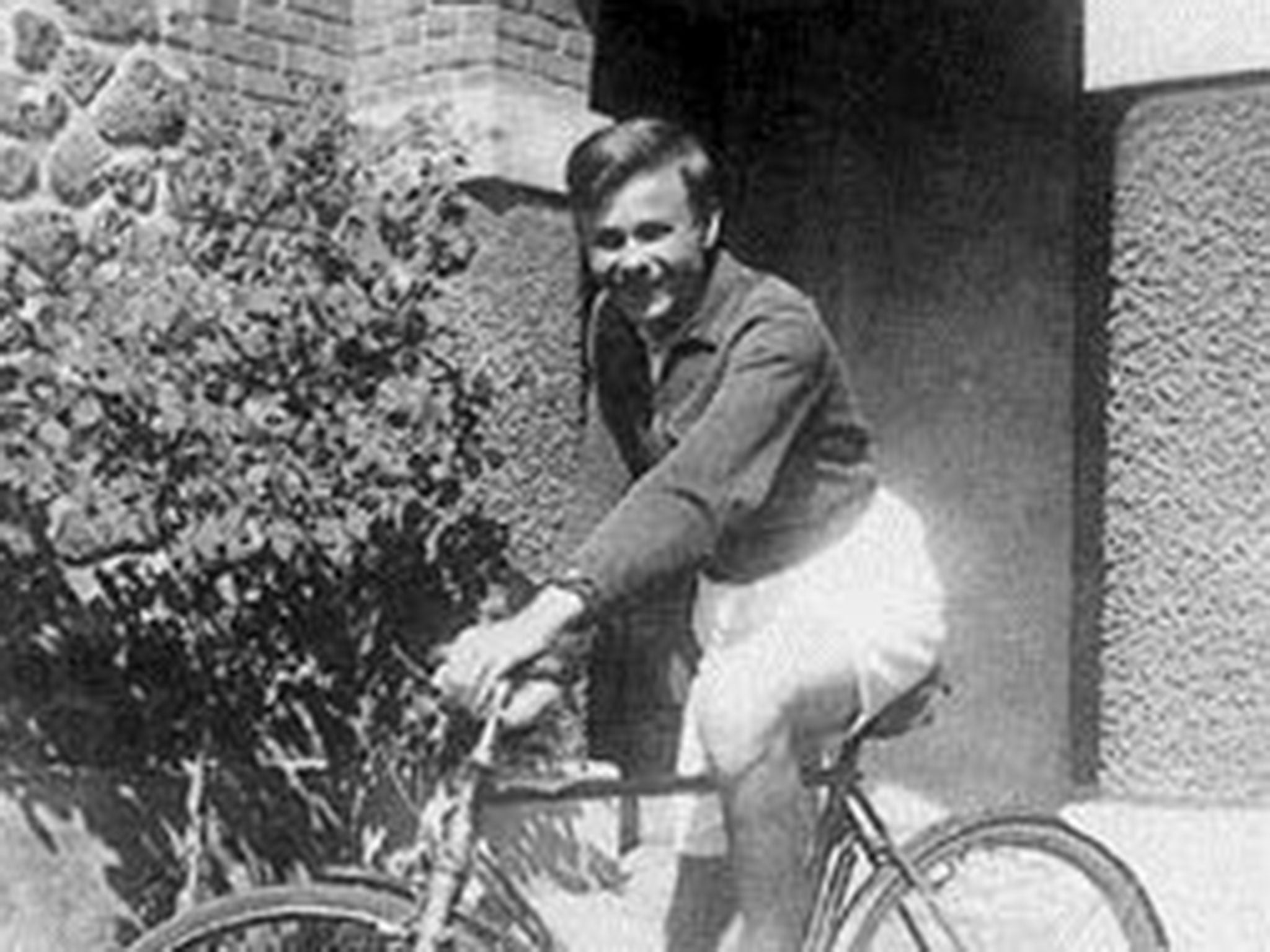

Riding his bicycle along the streets, beaches and dunes of his home town, Saint-Malo in Brittany, he accurately sketched or noted every detail of every German troop position, tank, aircraft or naval vessel he saw, including registration numbers and call signs and when and where they moved. It was vital information, smuggled past enemy lines, via resistance networks, to British agents of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) or to Britain itself via Marseilles or Gibraltar. British Intelligence said his work had been a significant factor in allied planning for the Normandy landings.

After capturing Saint-Malo in June 1940, the Nazis turned the old fortress port into a key brick in their "Atlantic Wall" against any allied invasion. Local resistance fighters could not easily emerge from their hide-outs. A schoolboy, and boy scout, could. Having picked him out because of his art skills at school, and tested his loyalty, the Resistance found ways to keep him out of classes so that he could cycle past Nazi fortifications, smiling and acting in awe of the German troops, who would give him sweets and teach him German words, not all of them appropriate for a schoolboy. Back home, he would write down his notes and do his croquis (sketches). After the war, he became known locally as Le croqueur des défenses Allemandes (the sketcher of the German defences).

The Resistance also arranged a cover under which young Pierre could take the train to Paris, via Rennes, every weekend "for family reasons". In fact, his family believed he was going to the capital for meetings of Les Eclaireurs de France, the equivalent of the Boy Scouts. Under the noses of the German occupiers in Paris, he would "drop" his sketches and notes to a French-Polish woman agent codenamed Raymonde.

These would find their way to Britain via Resistance couriers, the British embassies in Sweden or Portugal or agents in Marseilles of Gibraltar. The schoolboy's sketches were incredibly accurate, almost draughtsmanlike. He would go up to the highest points of Saint-Malo to sketch German naval vessels from above, including the positions of their big guns.

Pierre Léonce Demalvilain was born in the ancient town of Soissons, in the Aisne department of Picardy,in 1926, but brought up in Saint-Servan, outside Saint-Malo, 20 miles south of Jersey. Both his father and grandfather had been mayor of Saint-Servan (Pierre would many years later become deputy mayor). He was still only 13 and was attending the College de Saint-Servan (now the College Charcot) in Saint-Malo when the Nazis marched into the port before moving on to take Jersey and the Channel Islands. Later in the year, the RAF began bombing Nazi positions in Saint-Malo, close to his home and school.

"We were told to go down to the shelters," he recalled. "But I wanted to see what was going on. I snuck up to the third floor to watch the bombing but an adult stranger showed up and began asking me questions. He later took me to a man in Pontorson who asked me if I had a good memory, if I knew how to draw, if I loved my country and if I could keep my mouth shut. I said yes. They give me petits boulots [little jobs] and on 1 July, 1941, I formally pledged my allegiance to the resistance and signed up. To everyone outside my family, I became Jean Moreau. I delivered all my notes and drawings to a man known as Dr Andreis."

Dr Andreis was presumably an exiled Polish officer, one of those who had fled after their own country was occupied by the Nazis in 1939, set up the F2 resistance network along with British agents and French résistants, and fought their enemy on the soil of France. Polish forces later went on to capture Monte Cassino in Italy.

When the F2 network in Brittany was rumbled by the Germans in 1942, and many resistance fighters sent to concentration camps, Demalvilain survived and on 1 July 1942, a year to the day since he signed up with the resistance, he joined a Franco-Belgian resistance network known as Delbo-Phénix. He remained with them until American forces liberated Saint-Malo in August 1944.

He recalled one of his most dangerous missions, at Lanhélin, south of his home. British agents had asked him to try to find a Luftwaffe bomb depot suspected of being used for bombing missions on British cities.

"I was trying to cross some barbed wire when a German sentinel caught me and took me with him to a building full of bombs. Suddenly I heard voices approaching, his officers criticising him for being away from his post. He told me to get the hell out of the base and I ran. The RAF bombed the depot soon afterwards."

After the liberation of France, Demalvilain joined the regular French army and served in Indochina with the Marine Infantry Tank Regiment (RICM), a light cavalry regiment which became the most decorated regiment of the French army. When the French pulled out of Indochina, he stayed on, running plantations, before moving to Africa to do the same.

Back in Saint-Malo, he was shocked by the number of collabos (French who had collaborated with the Nazis) in positions of power. He was named an Officer of the French Legion of Honour. He is survived by his wife Jeanine, his son Bertrand and grandson Louis.

Pierre Demalvilain, resistance fighter and war veterans' activist: born Soissons, Picardy, France 6 July 1926; Chevalier de la Legion d'Honneur; married Jeanine (one son); died Saint-Malo 26 October 2015.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies