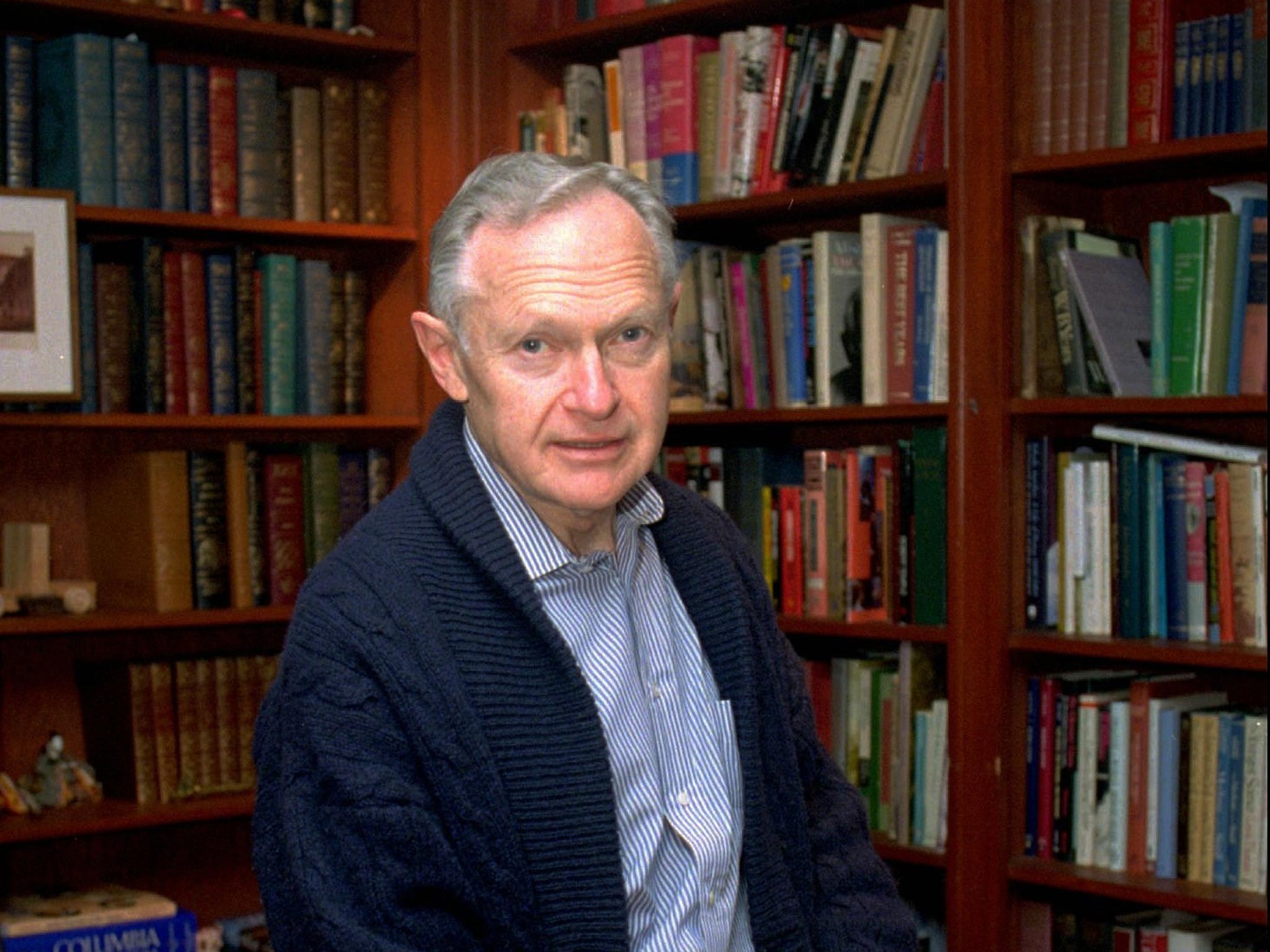

Sherwin Nuland: Surgeon and author whose celebrated work 'How We Die' sought to make its readers face the inevitability of death

Sherwin Nuland was a surgeon and author who unshrouded death in How We Die, a best-selling book that became a classic of medical literature. He spent years as a surgeon at Yale-New Haven Hospital then turned to writing and produced a series of books that illuminated how human life evolves, and ultimately ends.

How We Die: Reflections on Life's Final Chapter received the 1994 US National Book Award for non-fiction and was translated into numerous languages. The book presents accounts of death by various causes – heart attack, cancer, Alzheimer's disease, murder – in such raw detail that some readers declared themselves unable to finish it.

Its publication coincided with an intensifying debate about death with dignity, as it was called – an outcome that is, in Nuland's view, difficult to achieve. "It's unnatural to believe death usually has a beauty and a concordance and is usually a coming together of your life's work," he once said. "It leads to frustration for the patient. And it leaves grieving families convinced they did something wrong."

Nuland began the book by describing the first death he witnessed as a doctor. It happened to be his first patient, a 52-year-old man who seemed stable upon arrival at the hospital but was gripped by a massive heart attack. Nuland opened the patient's chest in a futile effort to save him and held in his hand the man's fibrillating heart. It felt, Nuland wrote, like a "bagful of hyperactive worms." Then, Nuland watched "something stupefying in its horror."

The patient, he wrote, "whose soul was by that time totally departed, threw back his head once more and, staring upward at the ceiling with the glassy, unseeing gaze of open dead eyes, roared out to the distant heavens a dreadful rasping whoop that sounded like the hounds of hell were barking." The sound, Nuland later realised, was the so-called death rattle. "Now you know," a more seasoned colleague told him, "what it's like to be a doctor." The National Book Award citation honoured Nuland for a style of writing that was "vivid, straightforward, at times almost painful to read" and that "strips the act of dying of all its romantic aspects."

Nuland's work transcended death to encompass the marvels of a healthy human organism, a topic that he addressed in The Wisdom of the Body (1997), later republished as How We Live. His other books included: Doctors: The Biography of Medicine (1988), The Mysteries Within (2000), The Art of Aging (2007), The Uncertain Art: Thoughts on a Life in Medicine (2008) and The Soul of Medicine (2009). He also wrote biographies of Leonardo da Vinci and Maimonides, the Sephardic Jewish physician and philosopher. But he was best known for his insights into death, a topic with which he said he had a "unique relationship."

He was born Shepsel Ber Nudelman in 1930 to a Yiddish-speaking family of immigrants in the Bronx. His grandfather and two uncles had made their way from Russia, only to die of tuberculosis. A brother died of an infectious disease before Nuland was born, while his mother died of cancer when he was 11.

"The whole atmosphere was one of looming tragedy," Nuland he recalled. "I never had a conscious fear of death, but I did have a conscious fear of sickness. By the time I completed medical school that fear was gone."

His father, Meyer Nudelman, was a garment-district sweatshop worker who struggled to walk. Nuland recalled fearing that his father would drop him when he carried him home from hospital, where he was treated for diphtheria. Nuland later realised his father had been suffering from syphilis. He wrote Lost in America (2003), a memoir about his father and the difficulty of reckoning with his legacy.

Meyer Nudelman was described as being deeply proud of his son's accomplishments, which included a bachelor's degree from New York University in 1951, a medical degree from Yale University in 1955 and appointment as chief surgical resident. But in the early years of his career, Nuland descended into a depression so severe that a lobotomy was considered. He underwent electroshock therapy, emerged from the depression and continued his work at Yale, where he taught and practised for years.

Despite the candour with which he discussed the limitations of medicine, he also maintained his belief in its possibilities. "We have had a rewarding relationship, the belly and I," he wrote in Wisdom of the Body.

Nuland observed that in writing How We Die he became so acquainted with the end of life that "instead of my belonging to death, death now belongs to me." He argued that "both individual fulfilment and the ecological balance of life on this planet are best served by dying when our inherent biology decrees that we do."

As for how to live before that time comes, his philosophy was perhaps revealed in the epigraph that he chose for his memoir of his father. It was a line attributed to the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria: "Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a great battle."

One of Nuland's four children, Victoria, is US assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs. He died of prostate cancer.

EMILY LANGER

Shepsel Ber Nudelman (Sherwin Nuland), surgeon and author: born New York 8 December 1930; married (four children); died Hamden, Connecticut 3 March 2014.

© The Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies