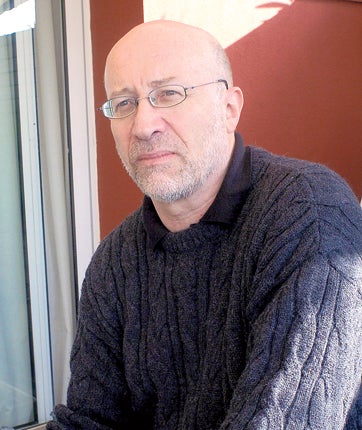

Tony Judt: Celebrated academic and historian of modern Europe who remained eloquent in the face of devastating illness

Tony Judt was a renowned British historian and intellectual who won accolades on both sides of the Atlantic for his tome on post-war 1945 Europe, but was equally known for his outspoken and stingingly controversial essays on the state of Israel, Britain's and Europe's futures and American foreign policy.

Judt described himself as a 'universalist social democrat' and later in life displayed a profound suspicion of left-wing ideologies, of identity politics, and of the American role as the world's sole superpower.

Diagnosed in Autumn 2008 with Lou Gehrig's disease, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Judt decided to write a series of essays that took an intensely personal and reflective turn. He started writing about his illness and personal memories as the incurable disease attacked his nervous system, ravaging him with devastating speed. Within months, he was a quadriplegic who needed an apparatus to help him breathe. Yet his mental faculties were undiminished and he found himself on an intellectual journey that one observer called 'a forced march of the mind.' His musings and reflections culminated in his final book, 'Ill Fares the Land' published in March this year, which was deliberately written as a letter to young people. In an interview in the same month he explained, 'It's about not forgetting the past, about having the courage to look at the present and see its faults without walking away in disgust or scepticism. It's about believing.'

The son of Jewish émigrés, Tony R Judt was born on 2 January 1948 in Putney, south London into a secular Jewish family. His mother's parents had emigrated from Russia and his father was from Belgium and descended from a line of Lithuanian rabbis. At the age of 15, following a year on a kibbutz in Israel, Judt became active in the Jewish Labour Youth Movement, Dror, and served as the organisation's national secretary from 1965-67. 'I was the ideal recruit, articulate, committed and uncompromisingly ideologically conformist,' he wrote in an autobiographical sketch for The New York Review of Books in February 2010.

However, Judt soon turned away from the Zionists' utopian vision after spending several weeks as a translator with the Israeli defence Forces in the newly conquered Golan Heights, after the Six-Day War in 1967. He was troubled by the nonchalant and callous attitude of the Israeli officers he worked with, later calling them 'right-wing thugs with anti-Arab views.'

Upon returning to England, he went to read History at King's College, Cambridge, where he earned his bachelor's degree, in 1969, and his doctorate in 1972. In between, he studied at the prestigious Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris. His dissertation, on the French socialist party's re-emergence after World War I, was published in France as La Reconstruction du Parti Socialiste: 1921-1926 (1976). His love affair with French politics continued and in 1979, he followed up with 'Socialism in Provence, 1871-1914: A Study in the Origins of the Modern French Left', and in 1986, he published 'Marxism and the French Left: Studies on Labour and Politics in France, 1830-1981'. These relatively specialist works led to two interpretive studies of French post-war intellectual life, 'Past Imperfect: French Intellectuals, 1944-1956' (1994) and 'The Burden of Responsibility: Blum, Camus, Aron and the French Twentieth Century' (1998).

Judt shocked many French and American intellectuals with these last two books as he dared to criticise the Soviet Union and third-world revolutionary movements. His target, he wrote, was 'the uneasy conscience and moral cowardice of an intellectual generation.' These publications established Judt as a historian whose ability to see the present in the past gave his work an unusual air of immediacy. Increasingly he inclined towards free-ranging inquiry across disciplines, pursuing a wide range of his interests reflected in the essay collection 'Reappraisals: Reflections on the Forgotten Twentieth Century' (2008).

Following teaching spells at Cambridge, Oxford and the University of California at Berkeley, Judt started his affiliation with New York University in 1987. It was there that Judt became the founding director of the Remarque Institute, where he promoted and shaped the historical study of Europe since 1995. Under his directorship, it became an important international centre for the study of Europe, past and present. He wrote nine books, mainly on the history of politics and ideas in Europe, and was a frequent writer of combative essays, reviews and op-ed pieces. His skepticism about the future of the European Union found expression in a sharply polemical, pamphlet-length book, 'A Grand Illusion? An Essay on Europe' (1996).

As a regular contributor to the New York Review of Books, Judt was known for his controversial writings about the Middle East. Never one to shy away from controversy, in 2003 Judt sparked a bitter debate when he argued that the Jewish state had become an 'anachronism' and he outlined a one-state solution to the Israel-Palestinian problem, proposing that Israel accept a future as a secular, bi-national state in which Jews and Arabs enjoyed equal status.

Judt's career reached its zenith in 2005 with the publication of 'Post-war: A History of Europe Since 1945,' a hefty book that became a Pulitzer Prize finalist. Intellectual historian Louis Menand called Judt's scope 'virtually superhuman.' Yale historian, Timothy Snyder described it as 'the best book on its subject that will ever be written by anyone'. Critics on both sides of the Atlantic considered the tome a masterful account of Europe's recovery from the wreckage of World War II. In 2009, the Toronto Star called it the best historical book of the decade. It proclaimed, '"Postwar" was 'perhaps the most astonishing feat of synthesis ever achieved, as he (Judt) managed to weave every country and every major political and cultural trend into a seamless narrative.'

With the crushing news of his illness in 2008, which rendered him helpless and a quadriplegic within a few months of diagnosis, Judt contemplated euthanasia. 'There are times when I say to myself, this is so damn miserable I wish I was dead, in an objective sense of I wish I didn't have to get up this morning and do it all over again,' he remarked. 'I've thought about euthanasia a lot, not for tomorrow, but one has to plan for it because the likely trajectory is that you lose your capacity to express yourself long before you die.'

Despite his illness, Judt continued giving public lectures without the aid of notes, granting interviews and writing for the New York Review of Books. Words, for Judt, were a way of making sense of his life and a weapon in his battle against his illness. He believed, 'words can make the illness a subject I can master, and not one that one simply emotes over.'

In 1996, Judt was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and in 2007, a corresponding Fellow of the British Academy. In 2009, he was awarded a special Orwell Prize for Lifetime Achievement for his contribution to British Political writing.

In his final book, 'Ill Fares the Land', a passionate call for a re-engagement in politics, he reflected and wrote, 'Something is profoundly wrong with the way we live today. For 30 years we have made a virtue out of the pursuit of material self-interest... The materialistic and selfish quality of contemporary life is not inherent in the human condition. Much of what appears 'natural' today dates from the 1980s: the obsession with wealth creation, the cult of privatization and the private sector, the growing disparities of rich and poor. And above all, the rhetoric which accompanies these: uncritical admiration for unfettered markets, disdain for the public sector, the delusion of endless growth.'

Shortly before his death Judt was described as having the 'liveliest mind in New York'. He died at his home in New York following complications from the disease, aged 62. He is survived by his third wife, dance critic Jennifer Homans and their two sons Nicholas and Daniel.

Tony Judt, historian; born London, 2 January 1948; married Jennifer Homans 1993, two sons, Nicholas and Daniel; died Manhatten, New York, 6 August 2010

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies