Walter Bonatti: Ground-breaking mountaineer who played a crucial role in the first ascent of K2

Walter Bonatti could have made the first ascent of K2. He was the most talented member of the Italian expedition that climbed the world's second highest mountain in 1954, but at 24 he was also the youngest, relegated to a disappointing support role which nearly cost him his life. With the local Hunza porter, Mahdi, he had to carry up oxygen cylinders for the chosen summit pair, Achille Compagnoni and Lino Lacedelli, who at the last minute pitched camp some distance from the agreed site.

After a long exhausting day, arriving at nightfall, Bonatti was unable to reach the camp and it was too late to descend to a lower camp, so he was forced to spend a night in the open, without tent or sleeping bag, at 8,100 metres above sea level. It was a hideous ordeal, made worse by Mahdi's delirious attempts to hurl himself from the precarious snow ledge, but both men survived, descending to safer altitude at first light. Meanwhile, aided by the vital oxygen cylinders, Compagnoni and Lacedelli reaped glory for themselves and for Italy, reaching the summit late that evening.

The K2 experience left Bonattiembittered. Not only was his heroic sacrifice unacknowledged: the summit pair blamed him for the fact that they ran out of oxygen near the top, suggesting that he had stolen some of it. The accusation was patently absurd – Bonatti had neither mask nor adaptor to deplete the cylinders, and Compagnoni and Lacedelli were simply too slow – but the slur rubbed salt in the wounds of a man who, despite being one of the greatest mountaineers of all time, was quite thin-skinned and prone to controversy.

He came from a poor family and had a tough adolescence around his home town of Bergamo during the Second World War and it was only in 1948, aged 18, that he discovered climbing, on the limestone pinnacles of the Grignetta, near Lecco. From then on, as he wrote in his autobiography, The Great Days, "I was devoted heart and soul to rock faces, to overhangs, to the intimate joy of trying to overcome my own weakness in a struggle that committed me to the very limits of the possible."

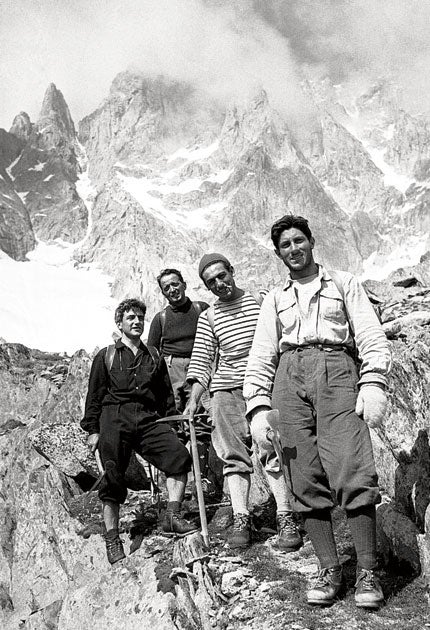

With a lesser climber, that might sound like posturing hyperbole, but with Bonatti the words rang true. He was bold and imaginative, with a resilient streak of asceticism. Right from the start he was repeating the hardest existing routes in the Alps and in 1951 he opened climbers' eyes with his first ascent of the East Face of the Grand Capucin – a beautiful, forbiddingly steep wall of compact granite in the Mont Blanc massif.

After the K2 debacle of 1954, as if in search of catharsis, he resolved to push himself even harder. The result was the first ascent of the spectacular Southwest Pillar of the Dru, familiar to every tourist who has ever gazed across the Mer de Glace from the railway station at Montenvers. On the first day Bonatti accidentally sliced off the tip of a finger with his piton hammer. He also dropped his stove, so was unable to melt snow for water.

At that stage most people would have packed it in, but he continued with his self-imposed task, for six days, quenching his thirst with two cans of beer, climbing alone up some of the steepest, hardest rock attempted at that time. After each rope length he had to descend, removing the pitons he had hammered into the rock, then climb laboriously back up the rope.

On Day Five, faced with an insurmountable overhang, he tied a bundle of pitons and wooden wedges to one end of the rope, hurled it over the roof, then swung free over the thousand-metre void, praying that his improvised bolas would hold in the jammed blocks of granite above. It did, and he survived to complete what became known as the Bonatti Pillar.

In 1956 Bonatti made the first complete ski-traverse of the Alps. In 1958 he returned to Pakistan as a member of Riccardo Cassin's expedition to Gasherbrum IV, which rises to 7,925 metres above sea level, just a few miles from K2. The final section up the North-east Ridge gave some of the hardest climbing ever achieved at that altitude. Bonatti led every pitch, supported by Carlo Mauri, and it was only 28 years later, in 1986, that the mountain was climbed again, when Tim Macartney-Snape found Bonatti's original abseil piton on the summit block.

Elsewhere in the world's greater ranges, Bonatti made the first ascent of Rondoy North in Peru; but his real legacy lies in the Mont Blanc massif, above his adopted home of Courmayeur. Earning his living as a mountain guide, he knew every nook and cranny of the range and in his spare time he was always exploring new corners, stretching his own personal limits. With Cosimo Zapelli in 1963 he made the first winter ascent of the Walker Spur, on the great North Face of the Grandes Jorasses. On the same face, with the Swiss climber, Michel Vaucher, he made the first ascent of the Whymper Spur. He was the first to dare to tackle the high remote Grand Pilier d'Angle on Mont Blanc, creating two routes with Zapelli and one with Toni Gobbi. It was also on Mont Blanc, in July 1961, that he survived one of the most epic disasters in alpine history.

Bonatti and his two Italian companions joined forces with four French climbers to attempt the unclimbed Central Pillar of Frêney. It would be the highest, hardest rock climb on the highest peak in Western Europe, but after a long, committing approach they were caught by a ferocious electric storm near the top.

After three nights huddled on a ledge, Bonatti realised that continuing was impossible and retreat by their approach route too dangerous. The only other option was a long, highly complex descent down an untried route on to the chaotically broken Frêney Glacier. The storm barely relented, and in white-out conditions Bonatti had to draw on all his instinct and experience to find a way down. Four of the team died from hypothermia and exhaustion, but without Bonatti's leadership it is doubtful whether anyone would have returned alive.

After operating for nearly two decades at the highest level, Bonatti decided cannily to retire from extreme alpinism. Ever the showman with a sense of history, he chose for his swansong an extremely hard new direct route up the North Face of the Matterhorn. He climbed it alone, over six days, in the winter of 1965 – the centenary of the first ascent of the mountain. Aeroplanes filled with journalists circled the mountain as he emerged from the face to stand and wave beside the summit cross. Thereafter he concentrated on his own journalism, travelling the world as a freelance photojournalist, drawn particularly to the wild empty spaces of Patagonia.

In 2009 the Italian Alpine Club finally accepted Bonatti's version of what happened on K2 in 1954. Meanwhile, in 2007, British climbers had made him an Honorary Member of the Alpine Club and invited him to the club's 150th anniversary celebrations in Zermatt. There, beneath the Matterhorn, scene of his greatest triumph, he was the star guest – a charming, charismatic man who gave no hint of the former controversies that had dogged his otherwise fulfilled long life.

Walter Bonatti, mountaineer and author: born 22 June 1930 near Bergamo, Italy; married firstly, partner to Rossana Podestà; died Dubino, Italy 13 September 2011.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies