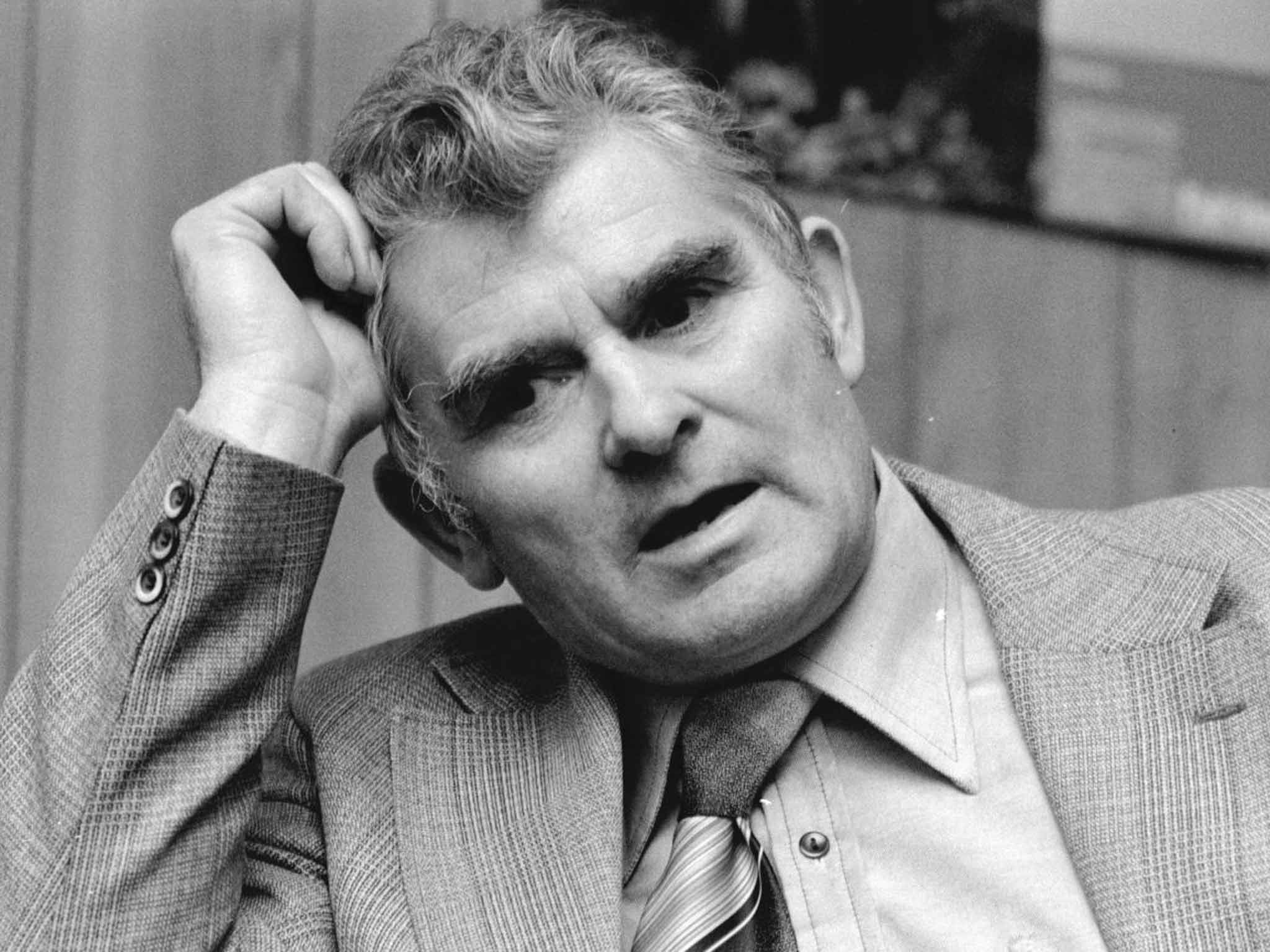

Bill Sirs: Steelworkers' leader whose political moderation saw him respected by many but opposed by Arthur Scargill

A genuine man of the people, he made no secret of the fact that his interest in union work was a result of the exploitation he saw around him

Bill Sirs was leader of the steelworkers' union, the Iron and Steel Trades Confederation, for 10 tumultuous years from 1975 until 1985. He led a national steel strike for 13 weeks in 1980 and received death threats during the miners' strike of 1984-85, but was one of the most respected, compassionate and likeable union leaders of his generation, winning the affection of those on both right and Left of the trade union and labour movement.

He negotiated the delicate balance between politicians such as Harold Wilson, James Callaghan, Ted Heath and Margaret Thatcher; trade union chiefs including the miners' leader Arthur Scargill; and captains of industry like Sir Monty Finniston, Sir Charles Villiers and Sir Ian MacGregor. He may not have boasted the charisma and oratorical powers of many of the Far Left speakers of that militant era, but he more than made up for that with his wit, wisdom and quiet common sense. He was a moderate and proud of it, and believed that moderation in all things, particularly union and political affairs, would win in the end.

Although he supported the miners' cause during 1984-85 he was determined not to allow the steel industry to be smashed, and made sure coal reached the steelworks. His moderate stance earned him the wrath of miners' pickets, who called him a "traitor" and "scab" and left him fearful for his safety. His rational, courageous and practical position during the miners' war with the Thatcher government was in sharp contrast to the verbal posturing of Far Left union chiefs who promised the miners everything but delivered little.

He was a genuine man of the people and kept himself fit and muscular throughout his life. He was a passionate non-smoker and irritated scores of delegates by successfully proposing a no-smoking ban at conferences. He was one of the stars of the TUC's annual pre-conference cricket team, and even in his sixties many of his union admirers – and envious, beer-bellied journalist friends – told him that his body was that of a 20-year-old Adonis.

It was this streak of determination which made him a successful union leader. The reason delegates did not always see him at breakfast was because he was jogging on the sea front. Once, he stopped his car in a country lane, and began doing 30 press-ups on the verge. A car stopped next to him and the driver, a Frenchman, looked down curiously at the huffing and puffing figure. When Sirs had finished he rolled on to his back gasping for air. The stranger told him, "Monsieur, the lady, she has gone."

He was born in 1920, one of 10 children, in the village of Middleton, near Hartlepool. His father was a hand riveter in the shipyards and was unemployed for many years of Bill's childhood. The children slept in two beds in one room using the "top and tail" system known to thousands of families in their circumstances. Bill would collected firewood and sea coal from the beaches, and at the age of 10 would rise at 6am to walk two miles to a newsagent's, pick up a wheelbarrow of newspapers and deliver them. During his lunchbreak he worked in a butcher's shop.

In spite of the privations he regarded himself as fortunate to live near the sea, where he could "swim for free" and catch extra food in the shape of lobsters, crabs, mussels and winkles. He admitted, however, that schoolwork suffered because of his jobs, and he regularly fell asleep at his desk.

He left school at 14, became an errand boy when he failed to get an apprenticeship, and landed a job carrying railway sleepers for 9s 10d a week. He went into the steel industry at 17, starting shift work with the South Durham Steel and Iron Company in a rolling mill, quickly learning the meaning of comradeship and rising via a variety of jobs to casting-bay crane driver.

When he was 21 he met Joan, later to be his wife, at a roller-skating rink. They married in 1941, obtained a rented house in West Hartlepool and lived there for many years.

From 1952-63 he devoted himself to union work, attending many of the educational functions and meetings at his own expense as it was difficult to persuade employers to pay for courses. He gained his first regional recognition in 1956, elected to the union's national negotiating committee. He quickly developed concerns regarding health and safety; he was once almost burned to death while working as a crane driver, when fuses in his cabin caused a fire. His physical fitness saved his life, because he was used, he said, "to shinning up and down the rope to the crane cabin like a monkey instead of using the stairs."

He made no secret of the fact that his interest in union work was a result of the exploitation he saw around him; he felt that some of it was the fault of union chiefs whose sole interest was in the best-paid workers. This view did not go down well with the hierarchy, but in 1963 he became a full-time ISTC organiser in Middlesbrough, turning down the chance to become a manager.

In 1970 he moved to Cheshire to cover that county, Lancashire and North Wales. He experienced his first works closure in Irlam, and never forgot the faces of the men as they walked out of the gates for the last time. He was talent-spotted by the ISTC as a future leader, and in 1972 became assistant general secretary.

Three years later he was appointed general secretary-designate, taking over from Dai Davies. In his 1985 book Hard Labour he recalled being "dropped in the deep end", and blamed Dai Davies; he was bitter that Davies had not shared the work with him. Then, when a vital meeting in London with British Steel Corporation management was held to discuss 20,000 job losses, Davies was absent. When Sirs returned to his office after battling with press and TV reporters, he discovered that Davies gone to Luxembourg: "Davies, sensing the difficulties ahead, retired almost immediately and left me with the task of guiding the destinies of the union."

When he heard in June 1983 that Ian MacGregor, BSC chairman, had moved to preside over the National Coal Board, he knew the country would be in for trouble, and he was right. He knew MacGregor would go head-to-head with the militant NUM President Arthur Scargill and likened the forthcoming battle to "Goliath versus Godzilla". After his first meeting with MacGregor, Sirs had believed that he would keep his promise to review the decision to close the Consett steelworks in Co Durham. Weeks later he learned the bitter truth: MacGregor had done nothing.

As for Scargill, a man he also knew well, Sirs thought he could work with him, as he had with his moderate predecessor, Joe Gormley. Here again, his hopes were dashed, and he would describe Scargill as "a dangerous opportunist" who was untrustworthy. He soon came to believe that, in Scargill, he had shaken hands with a rattlesnake. He accused Scargill of undermining the steel strike by claiming that the steelmen wanted a 20 per cent wage increase, whereas they had only demanded a rise in line with inflation. He described Scargill's intervention as "damaging and utterly irresponsible, but that was the way he operated."

He was also critical of Scargill's decision to call his men out on a national strike in 1984 without a ballot following the closure of the Cortonwood Colliery in Yorkshire. During that terrible industrial conflict Sirs did what he could to help the miners without destroying his beloved steel industry and was a hero in the eyes of his own people. To the majority of the NUM hierarchy and the Far Left, though, he was a class traitor and a "Judas". Sirs could never understand why the TUC leadership ran scared of the miners, turning a blind eye to blatant intimidation and violence. "They were timid and apprehensive in a way I have never seen before," he said.

But Sirs reckoned he understood human nature better than Scargill, and knew men would not put their jobs on the line to save somebody else's job in another part of the country. He said: "That is human nature and a sad fact of life."

Sirs fought to smoke the militants out of the Labour Party he loved and fought hard to re-shape it. He was one of a handful of TUC leaders in favour of Britain's position in the EC. He opposed closures of steelworks but reluctantly accepted that working men were queueing up to take golden handshakes in the form of £20,000 redundancy payments. The lost battle to save Bilston steelworks in 1978 made him realise the grim truth that closures could not be prevented by militancy.

In retirement he took up golf at the Panshanger Golf Club in Welwyn Garden City, and took up charity work. He also enjoyed the company of his four grandchildren and two great-grandchildren, and travelled to Australia to see his daughter. His keep-fit obsession saw him in the local gymnasium at the age of 85, and he appeared on a BBC television programme, Approach to Life, about keeping fit in old age.

William Sirs, trade unionist: born 6 January 1920; General Secretary, Iron and Steel Trades Confederation 1975–85; married 1941 Joan Clark (died 2010; one daughter, one son); died 15 June 2015.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies