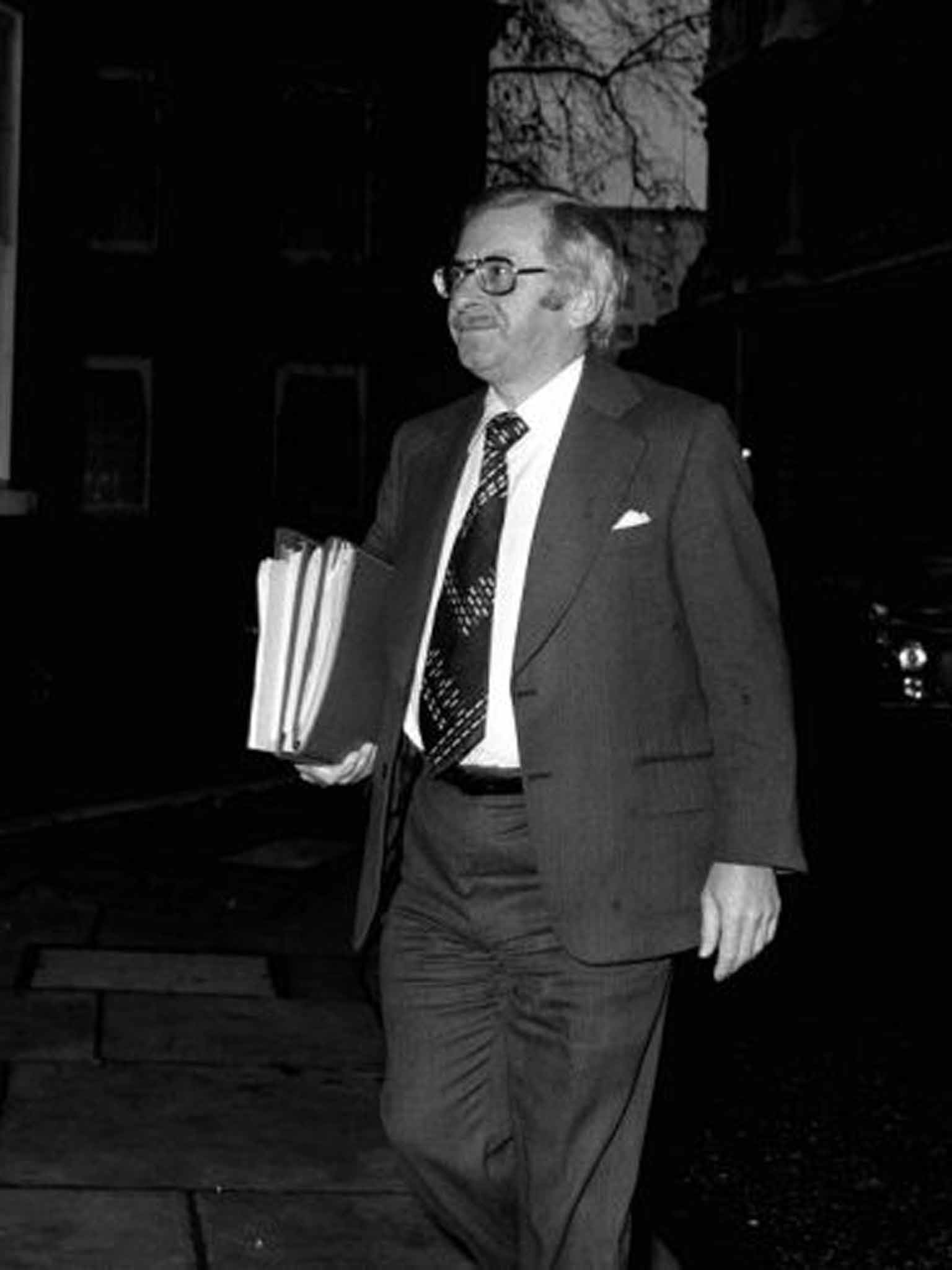

Lord Barnett: Politician who created the notorious Barnett formula although he intended it to be only an interim measure

The problem for a Chief Secretary to the Treasury is that he or she is concerned with anything to do with money, and virtually everything in government deals with money. If a Chief Secretary is to do the job properly there is no substitute for reading through a great volume of paper work. When dealing with detailed and complex financial problems affecting everything from nuclear power stations to housing, the method should be to read carefully through the papers and extract the information, preferably on one side of a single piece of paper. No Chief Secretary was ever more adept at doing this than Joel Barnett.

Barnett went to meetings at least as well-informed, usually better informed, than a minister was about his own department. This made him a pivotal member of the Labour government of 1974-79, working with Denis Healey, the Chancellor of the Exchequer. His importance in those years cannot be exaggerated.

As Chief Secretary, his main achievement was the introduction of cash limits on expenditure. At a time of high and variable inflation the control of spending plans in real terms, that is by inflation-proofing, was no longer possible, and cash limits were an essential way of maintaining a grip on spending plans. Following the importance attached to the tight control of public expenditure, Jim Callaghan decided that he wanted his Chief Secretary as a full member of the Cabinet.

To Barnett's horror, because he thought that it would only be a temporary measure, he had his name given to another important innovation concerning Scotland and Wales – the now notorious Barnett Formula. Rather than have extensive annual discussions on expenditure allocations in Scotland and Wales, a formula was devised as a percentage of total expenditure for each of the countries. Intended as an interim measure, it is still in use.

He was born in north Manchester; his father was a tailor. As he put it in his autobiography: "My parents were living in a small, terraced house in Barker Street, Manchester, just opposite Strangeways Prison. One biographical reference to me many years later said that I was born in 'Strangeways' – I had to explain it was the district, not the jail."

This remark encapsulates one of Barnett's strengths, a sense of humour, sometimes self-deprecating, which made him popular, and able to remain friends with powerful ministers whose requests for money he turned down. His father was born in Manchester but his mother was brought to England as a child; their parents were immigrants who had had to struggle. At the age of 10, having attended the Jewish Elementary School at Derby Street and Balkind's Hebrew School, he won a scholarship to a grammar school, Manchester Central High.

In 1937, when he was 14, the tailoring industry was going through a bad patch and his parents felt that the 10 shillings a week he could earn would be invaluable; his formal education ended. The first seeds were sown of his ambition to become a Labour MP. "Many years later, when Shirley Williams and others argued in the Cabinet for the importance of children staying on at school I did not need convincing. I was possibly more aware than others that a £6-a-week Educational Maintenance Allowance would not easily persuade parents or children to forgo the £15 that could be earned."

As it did for many others, the Second World War transformed his life. He joined the army and was allocated to clerical work in France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany, finishing with the rank of sergeant. The army introduced him to a new and wider world which for the first time was non-Jewish.

After the war he worked in a small jewellery shop in Eccles but decided to return to his studies. It was at this time that he met his wife-to-be, Lilian Goldstone, at a Jewish club in Manchester. This was to be one of the most loving and enduring marriages for a politician I ever came across. They joined the Prestwich Labour Party and were kept going by Lilian's work as a secretary. "Even so, we were very hard-up, and when I was pursuing my studies by the fire, Lilian would go to bed early, not wanting to disturb me or to waste money on a fire in the other room."

Qualifying as an accountant, he was accepted as a partner in a one-man firm run by George Keeling, who retired after 12 months. Barnett worked every hour, building up a staff of about 70. There are many well-organised and hard-working people in the Commons, but none was more hard-working, better organised or more in control of his time.

Prestwich was Conservative but Barnett was invited to run for the council, becoming its only Labour member. In 1959 he fought Mark Carlisle, later Ted Heath's Education Secretary, in Runcorn. Crucially, he was to team up with friends – Edmund Dell, a powerful mind who was to become Jim Callaghan's Secretary of State for Trade and Industry, his intimate and lifelong friend Bob Sheldon and the Manchester designer Colin Hughes Stanton – in the formation of a Manchester Labour coffee house.

In 1961 he was selected for Heywood and Royton, a marginal seat held by the Conservatives. Three years later, by sheer organisation and hard work, he won with a majority of 816. Dell, Sheldon and Barnet made their names in the long, drawn-out and contentious debates of the 1965 Finance Bill. The Commons was impressed by Barnett's financial expertise, which contrasted with the sometimes woolly contributions of those with brilliant economic degrees. He made his maiden speech arguing the case for a simpler system of income tax. I remember thinking that here was a new colleague who knew what he was talking about. His speeches were unfailingly attractive; and he had the gift of not putting up the hackles of people to whom he was saying "No".

In the 1966 election Barnet had a large poster of Harold Wilson printed for his constituency and in the corner a picture of himself with the caption "Me too!" It went down a proverbial bomb. However, all was far from plain sailing. He wrote: "To our astonishment, when we came back ... in March 1966 with a substantial majority, there was no devaluation and growth was held back, in the interests, as we saw it, of maintaining an overvalued pound. An unlikely group of right and left-wing backbenchers got together – for a reason which escapes me now, we called our group 'Snakes and Alligators'. Bob Sheldon and I went to see many Cabinet ministers quietly ... Harold Wilson and Jim Callaghan, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, learnt of our campaign virtually within minutes.

"We did not succeed in our efforts but we succeeded in antagonising both Wilson and Callaghan. Up to now Callaghan had been quite friendly with Bob and myself ... but our activities put a strain on the relationship."

Following Labour's defeat in 1979 Barnett became Chairman of the Public Accounts Committee, an influential position. It was his decision, for instance, which led to the Chevaline updating of our nuclear weapons being made public and accountable.

In 1983 the Boundaries Commission absorbed Heywood and Royton into existing constituencies, all with sitting Labour MPs, and Barnett was made a peer. So high was Thatcher's opinion of him that she offered him the post of European Commissioner. Typically, he had treated her with courtesy and friendliness in their many clashes on finance matters. She was happy to make him deputy chairman of the BBC in June 1986, and after the unanticipated death of Stuart Young the following August he became acting chairman, reverting to deputy on the appointment of Duke Hussey.

Barnett was left in no doubt of Thatcher's hostility to the BBC; she called the licence fee a "compulsory levy, with criminal sanctions". It was his outstanding contribution, alongside Hussey, that he played it long and saved the BBC as we now know it.

Barnett became the Chairman of British Screen Finance in 1985, a trustee of the Victoria and Albert Museum and of the Halle Orchestra and chairman of the Hansard Society for Parliamentary Government. His 1982 book Inside The Treasury should be read not only by any minister, actual or aspiring, but by anybody who wishes to become a serious member of the House of Commons.

Joel Barnett, accountant and politician: born Manchester 14 October 1923; MP for Heywood and Royton) 1964-1983; Chief Secretary to the Treasury 1974-1979; cr. 1983 Life Peer; married 1949 Lilian Goldstone (one daughter); died 1 November 2014.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies