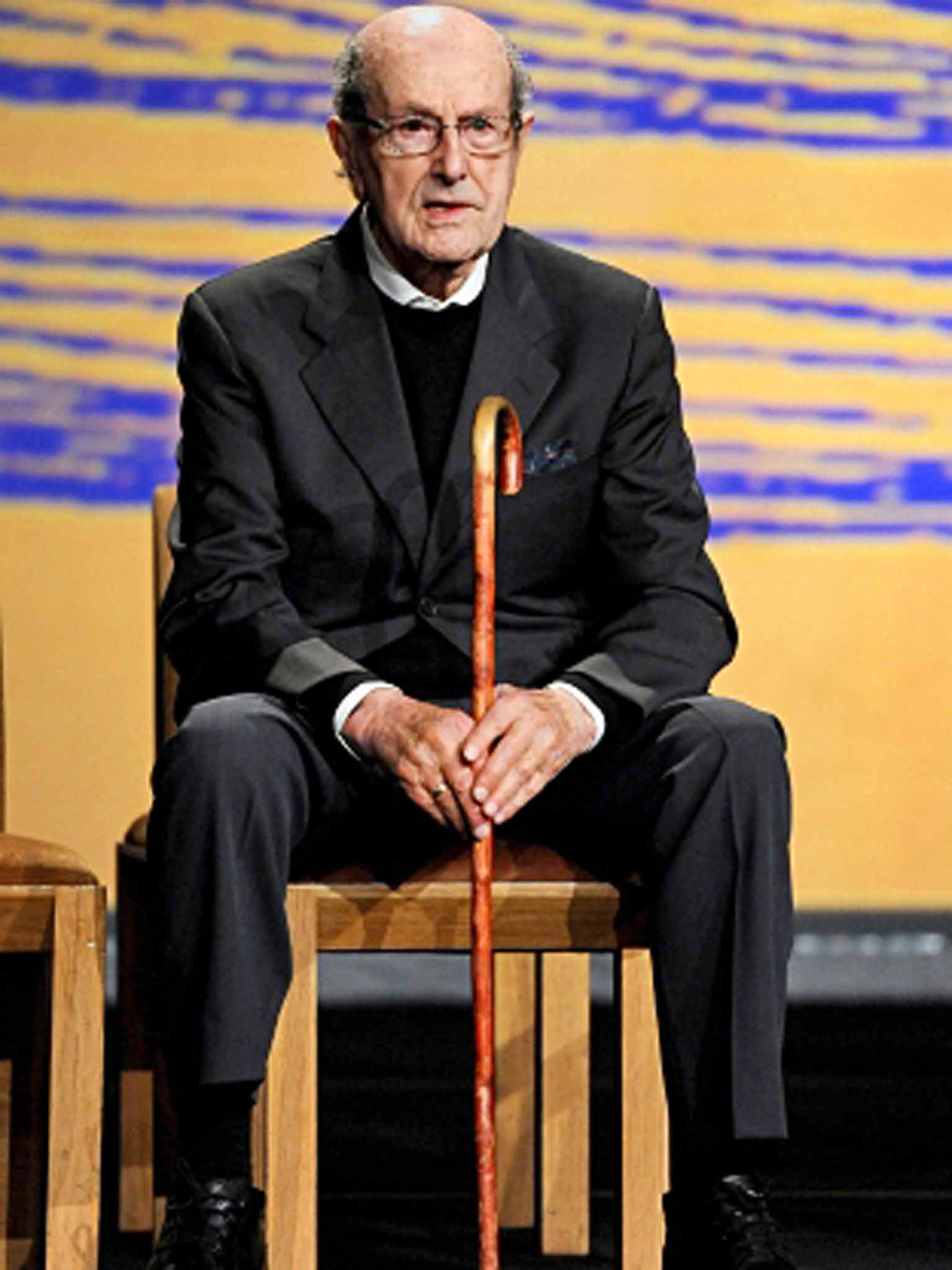

Manoel de Oliveira: Portuguese film director who continued to make his astute art-cinema well after his 100th birthday

A national pole vault champion and racing driver in his youth, his film career began in 1931 with an 18-minute silent documentary

Manoel de Oliveira, who has died at the age of 106, was believed to be the world's oldest film-maker. His final film, a short feature called The Old Man of Belem, had its premiere last November in Porto and was shown at last year's Venice Film Festival.

Oliveira's career began with a silent documentary about his home town of Porto, Portugal's second-largest city, in 1931. He made his first feature-length film in 1942, but his output was sporadic until he was 76 – at which point he began directing roughly a film a year.

Despite his huge output – more than 30 feature films and dozens of short films and documentaries – he achieved broader international recognition only in the 1990s and was best known as an art-cinema auteur. He was more than 100 years old when his last feature, the French-language Gebo and the Shadow, came out in 2012.

Oliveira was a regular at Cannes, where three of his films were nominated for the Palme d'Or, and where he was awarded a Golden Palm for lifetime achievement in 2008. The Venice Film Festival twice gave him career Golden Lions, in 1985 and 2004.

Oliveira's later work drew the interest of high-profile actors: his 1995 film The Convent starred John Malkovich and Catherine Deneuve in a romantic mystery. "Manoel de Oliveira is very, very special," Deneuve said in 2005. "He works all the time, he writes the script during the night."

In 1996 Oliveira said he had no plans to slow his work rate. "I'm in a hurry. I have too many stories to tell," he said. His other films included Belle Toujours, a 2006 follow-up to Belle de Jour by Luis Bunuel – with whom he felt an affinity – that caught up with its prostitute heroine.

Oliveira was born in 1908. He was a national pole vault champion and a racing driver in his youth. His film career began in 1931 with an 18-minute silent documentary, Hard Labour on the River Douro, about the conditions endured by river-workers in Porto, regarded as a classic of the avant-garde.

His first feature, Aniki-Bobo (1942), was a hit in Portugal, but its neo-realism, which used mainly child actors and anticipated the Italian school, drew the attention of the then-dictatorship's secret police, PIDE, which suspected him of subversion. He was later held without charge for 10 days before being released.

Opposition from the authorities was steadfast: the government of Antonio Salazar refused to give him funding for his films and the censors rejected his scripts; after Aniki-Bobo he didn't make another feature for 21 years. "I never had any political urges or activity," he said, "but they hated me all the same."

Oliveira also lost out in the 1974 military coup that toppled the dictatorship and installed democracy in Portugal: workers at the small textile factory he had inherited from his father seized control and ran the company into bankruptcy.

Manoel de Oliveira, film director: born Porto 11 December 1908; married Maria (four chldren); died Porto 2 April 2015.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies