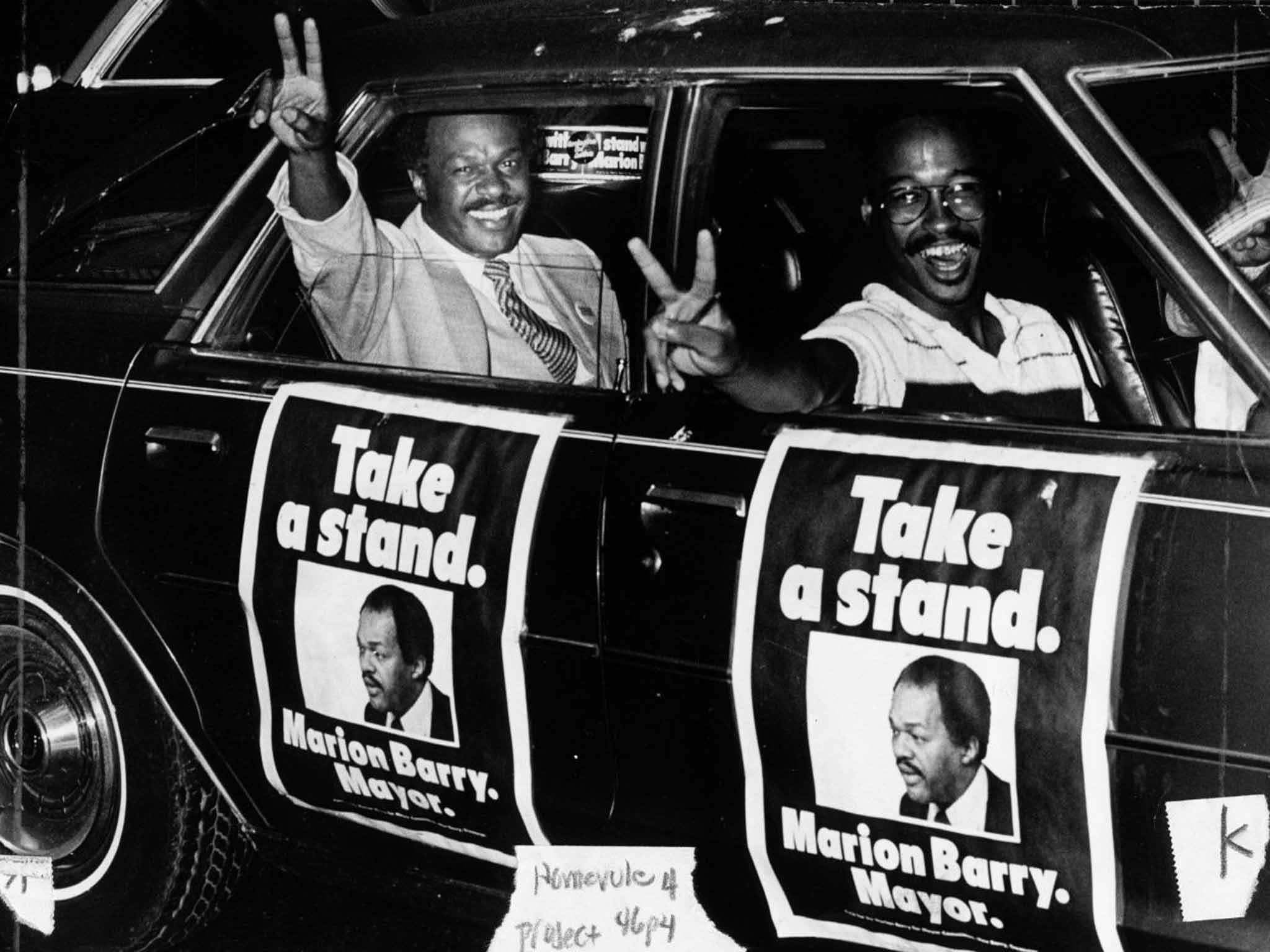

Marion Barry: Civil rights hero who went on to become mayor of Washington but was laid low by his personal demons

Marion Barry could have been a great man, an indomitable fighter for civil rights and the mayor who made Washington DC whole. Instead, he will be remembered above all as a racial polariser brought low by his demons, his career summarised by grainy images of him smoking crack cocaine with a former mistress at a downtown hotel.

What is incontestable is that for two decades, first for better and then for worse, Barry defined his adopted city. Not the imperial capital city of the superpower that would win the Cold War against the Soviet Union, but the majority-black, racially divided Washington DC of 600,000 inhabitants – the "last plantation", semi-disenfranchised and subject to the whims of a white dominated Congress, a state of affairs that largely persists to this day.

Barry arrived in Washington in 1965 as chairman of the Student Non-violent Co-ordinating Committee, a driving force of the civil rights movement, leading freedom marches, and organising voter registration and peaceful protest in the Jim Crow Deep South.

His gravitation to the SNCC was almost inevitable. He was born in rural Mississippi to a family of sharecroppers who fled the state's entrenched poverty and racism and moved north to Memphis, Tennessee, in search of a better life. His father died when Marion was five or six. But the boy made his own way, doing paper rounds, selling sandwiches and working as a waiter, even finding time to join the Boy Scouts, and rising to the top rank of Eagle. He was a good student too, and after high school went to Lemoyne College in south Memphis.

There he fell under the sway of two liberal white professors who believed passionately in Martin Luther King and the rightness of his cause. Barry's course was set. He became an activist, arrested for civil disobedience for his involvement in anti-segregation protest. After graduating from LeMoyne in 1958, he took a masters in chemistry at the historically black Fisk University in Nashville. By 1960 he was elected the SNCC's first chairman.

The job was peripatetic, taking him to every corner of the country. In 1965 he was sent to take charge of the SNCC in Washington, emerging as a champion for home rule for a black-majority city that in those days – in spirit if not geography – still belonged to the South. He was a good organiser, proving his mettle in helping restore calm after the 1968 race riots in Washington following King's murder.

Nor did he conceal his anger at the status quo; after President Nixon, who had opposed a holiday to honour the martyred King, called for one to celebrate the Apollo moon landing, Barry demanded, "Why should blacks feel elated when we see men eating on the moon when millions of blacks and poor whites don't have enough money to buy food here on earth?"

DC politics was the inevitable next step. In 1971 he ran for the School Board and was quickly elected its president. Three years later, when Washington was finally permitted a form of home rule, he was elected to the first city council. Then, on 9 March 1977, extremists linked to the radical Nation of Islam burst into the government building and took hostages. The crisis was resolved peacefully, but not before Barry had been shot and wounded as he entered the building. He had became a hero – just in time for the next mayoral race.

For the next 20 years Barry bestrode city politics. He was elected in 1978, and then again in 1982. At first all went well; the new mayor preached racial reconciliation, while a property boom ensured the city's coffers were full. But tensions gradually arose; first with Washington's middle class black establishment, which looked down on the man with the coarse accent and uncultured ways that it regarded as a cotton-picking sharecropper's son; then with the city's whites, entrenched in the wealthy north-west quadrant of the city, oblivious to the privations of poor black life, who simply wanted a safe and decently run city.

Barry's troubles started in earnest in his second term. Reports surfaced of his addictions to women, alcohol and drugs. The city's finances came under strain, and Barry looked not to the diminishing black middle class, by then fleeing an increasingly violent Washington for the Maryland suburbs, but to his natural fief in impoverished south-east DC.

For all his troubles, Barry's control of the city machine was absolute. In 1987 he easily won a fourth term, despite the misgivings of The Washington Post and the dismay of most white residents. To them Barry's message was blunt. "Get over it," he declared, almost revelling in the polarisation as he portrayed himself champion of the neglected and the oppressed.

But the city's downward spiral accelerated. Barry's personal indisciplines could no longer be hidden. Girlfriends came and went. At public events his speech was slurred, and appointments were scheduled later in the day to allow him to recover from the previous night. All the while violent crime grew, fuelled by gang wars over the latest drug of choice, crack cocaine. In 1991 there were a record 479 murders in Washington, "Murder Capital of the USA". And crack cocaine proved Barry's personal downfall.

The FBI had long been investigating reports of drug use by the mayor. On the night of 18 January 1991 they got their man, caught on video smoking crack with a former girlfriend, Hazel "Rasheeda" Moore. "Bitch set me up, I shouldn't have come here," Barry famously declared as Bureau agents burst into the room at the Vista Hotel.

But even this disgrace, followed by a six-month jail sentence, could not keep Barry down. In 1994 he ran for mayor and won again. If the faith of his poor supporters remained intact, however, the powers of the office did not. In the intervening period Washington had effectively gone bankrupt and from 1995 the city was largely run by a financial control board, overseen by the newly Republican Congress.

In 1998 he announced he would not seek a fifth term, but in 2004 won re-election to the council, representing the deprived Ward 8, a post he held, despite diabetes and other health problems, until he died. Typically, scandal continued to dog him: claims of unpaid taxes, arrests for alleged drunk-driving, and accusations of graft. But nothing seemed to stick. To the end, Marion Barry somehow still controlled the system.

Marion Shepilov Barry, civil rights activist and politician: born Itta Bena, Mississippi 6 March 1936; married four times (one son); died Washington DC 23 November 2014.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies