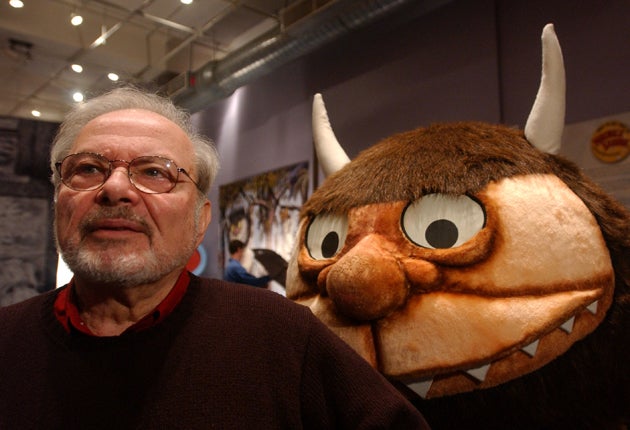

Maurice Sendak: Call of the wild

The truth behind the children's classic 'Where the Wild Things Are' – now a $100m movie – is that growing up can be painful. As its author well knows

At just 338 words, Maurice Sendak's Where the Wild Things Are must be among the shortest books in the canon of popular fiction.

Yet those 338 words and the magnificent illustrations that accompany them have charged the imaginations of children ever since they were published in 1963. Having already sold 10 million copies worldwide, they have this year inspired a 300-page novelisation by Dave Eggers, a $100m Hollywood movie by Spike Jonze (from an Eggers script), and an HBO documentary by Jonze about Sendak's life, which some critics have described as the most interesting element of the triptych.

Where the Wild Things Are is the story of Max, an angry young boy in a wolf suit who argues with his mother and is sent to bed without his supper. Confined to his room, Max imagines himself away to a mysterious land where he becomes king of a tribe of formidable monsters, "the wild things". Says critic Nicholas Tucker, an expert in children's literature, "The monsters in Where the Wild Things Are turn out to be rather less monstrous than the child."

Much of Sendak's work delves into the borders between dream and reality, where the dark primal impulses of children are set loose. When his most famous book first appeared 46 years ago it was not children that feared its contents, but adults. The Journal of Nursery Education's review of Wild Things famously included the caution: "We should not like to have it left about where a sensitive child might find it to pore over in the twilight."

Classic children's literature contains many unpleasant tales of children lost, tortured and terrified. The Brothers Grimm, Lewis Carroll and Hans Christian Andersen all punished their young characters for curiosity, selfishness and other sins. But, as Tucker explains, "When Sendak began writing, there had been a reaction against 19th-century cautionary stories of children burning themselves to death with matches and so on. Children's literature between the wars went through an upbeat, Christopher Robin-type optimism. Sendak was the first writer after the war to bring back some of those suppressed horrors."

"Childhood is a hard story and that comes from my own experience," Sendak told Jonze in an interview for Dazed and Confused magazine. The youngest of three children, he claims his birth, in Brooklyn in June 1928, was an accident. His parents Sarah and Philip, a dressmaker, had emigrated from a shtetl outside Warsaw before the First World War. Racked with illness during his childhood, Sendak grew up an outsider, forced to watch other children playing from his bedroom window. "If you're looking at those games from outside and are seen as too delicate to take part in them yourself," says Tucker, "you could quickly form a view of the human race as fairly aggressive and confrontational."

Sendak also developed a love of books from his time spent bedbound. He and his brother wrote and illustrated their own short stories as children, but he claims his imagination was first seriously fired by seeing Walt Disney's classic animated film Fantasia aged 12. After graduating from high school he took a job as a window dresser at the toy store FAO Schwarz. It was the store's children's book buyer who saw his work and recommended him to his long-standing editor Ursula Nordstrom, who invited him to illustrate his first book, Marcel Aymé's The Wonderful Farm, in 1951.

Despite such markers of hopeful American capitalism as Disney and Schwarz in his life, Sendak's work was always overshadowed by darker themes. His family lived with memories of both the Great Depression and the Holocaust, which had claimed many of their relatives. Mickey, the protagonist of his 1970 book In the Night Kitchen, is a young boy who finds himself in a fantastical baker's kitchen by night and is almost baked into a cake by unsuspecting (or is it unfeeling?) cooks. In a recent interview Sendak suggested that the bakers – with their Hitler-esque moustaches – were a reference to the Holocaust.

In 2003, Sendak approached the gay socialist playwright Tony Kushner, writer of Angels in America, to collaborate on a version of the children's opera Brundibar. An allegorical riposte to Nazi tyranny, the opera was originally written by Czech composer Hans Krasa and staged at a Jewish boys' orphanage in Prague in 1942. After just three performances, the German occupiers transported its entire cast and crew to the Terezin concentration camp, where it was performed for the inmate population a further 55 times. Krasa and almost all the children of the cast were finally murdered at Auschwitz.

The distinctive characters of Sendak's imagination are not good-looking picture-book children. Rather they are frequently, like himself, somewhat stout and gnomish. "In America they use some phrase like 'Eurocentric' to describe it," says Tucker, "which is actually a euphemism for Jewish. His children are dark, with stumpy figures – not your standard, Anglo-Saxon Janet and John types."

Ever an outsider, Sendak's childhood and career were further complicated by his homosexuality. "All I wanted was to be straight so my parents could be happy," he told an interviewer from The New York Times. "They never, never knew." Similarly, a publicly gay children's author would have had a difficult time dealing with the conservative sensibilities of parents in the mid-20th century when he was first at work.

It wasn't just Wild Things that met with controversy. When In the Night Kitchen was first published, its images of Mickey jumping naked about the page saw it censored in a number of US states. Sendak was not impressed. "Adults will take their kids to museums to see a lot of peckers in a row on Roman statues and say 'that's art dearie', and then come home and burn In the Night Kitchen," he said. "Where's the logic in that?"

Sendak undoubtedly makes an ideal mentor for Jonze, his 40-year-old protégé; both are revolutionaries within their respective fields. Much has been made of Jonze's grapple with the Warner Brothers studio for artistic control of the Wild Things film, but he also argued with his friend Sendak over certain aspects of the adaptation. Most crucially for fans, the Max of the movie doesn't watch his own bedroom transform into a forest, but instead runs away from home altogether to the fantasy land of the wild things.

When Max finally returns home, chastened by his experiences, he finds his dinner waiting for him. Like many of Sendak's child protagonists, Jonze's movie – six years in the making, even by modest estimates – has had to struggle through horrors to reach maturity. The film, which opens in the UK on 11 December, comes to cinemas in the same season as the animated adaptation of Fantastic Mr Fox, made by Jonze's Hollywood contemporary Wes Anderson. Jonze and Anderson are actually a generation younger than the baby boomers who were originally exposed to the works of Sendak and Dahl. So, despite the director's battles with the studio bosses, it's perhaps equally significant that the children who first loved Where the Wild Things Are and Fantastic Mr Fox are now of an age to be running movie studios, and giving hip young directors multimillion-dollar budgets to re-imagine their childhood icons on film.

Sendak, whom Jonze took great pains to include in the film-making process, lives alone with his beloved dogs in small-town Connecticut. Now 81, he lost his partner of 50 years, the psychoanalyst Eugene Glynn, in May 2007. His own health remains shaky: he had his first heart attack at 39, a triple bypass operation at 80, and suffers from recurring bouts of depression. Yet he continues to work, both as an illustrator and as a designer for theatre, opera and ballet. Tellingly, Sendak's heroes are not his forebears from the world of children's literature, but Keats, Blake and Emily Dickinson. His German Shepherd dog is named Herman, after Herman Melville, author of Moby Dick.

To lovers of his work, Sendak is more than worthy of a place in the pantheon alongside such figures. As his friend and collaborator Tony Kushner says, "He's one of the most important, if not the most important, writers and artists ever to work in children's literature. In fact, he's a significant writer and artist in literature. Period."

A life in brief

Born: Born: Brooklyn, New York, 10 June 1928, to Sarah (née Schindler) and Philip Sendak, Polish Jewish immigrants.

Early life: Decided to become an illustrator at age 12. Attended Art Students League in New York in early 1950s.

Career: Illustrated dozens of books before writing his own, Kenny's Window, in 1956. It was followed by the internationally acclaimed trilogy Where the Wild Things Are, in 1963. He later wrote In the Night Kitchen in 1970 and Outside Over There in 1981. He also designed stage productions of The Magic Flute and The Nutcracker in the 1980s and, more recently, created the children's television programme Seven Little Monsters.

He says: "We heard horrible, horrible stories, and we loved them, we absolutely loved them. But the three of us – my sister, my brother, and myself – grew up very depressed people." – on the fairy tales he listened to as a child.

They say: "I love him, and I love his books... When you love something from that age, you end up loving it really deeply because the images are there way down inside you." Spike Jonze, director of the film of Where the Wild Things Are.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies