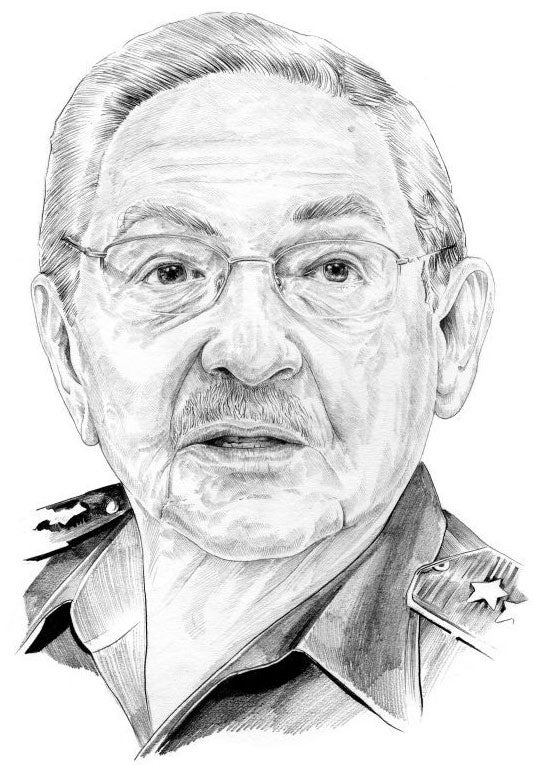

Raul Castro: Last of the great Communists

First a commander of the Cuban military, now President, how far will Fidel's stiff brother bend to the new world?

When Raul Castro came on the air to inform the nation in a characteristically brief speech that Cuba’s ancient quarrel with the superpower across the water was – hopefully – coming to an end, Cubans turned up their TV sets, clapped their hands and some even burst into tears.

It certainly was not the old patriarch’s rousing style of delivery that inspired this high emotion. The 83-year-old has never shared his brother’s taste for delivering hours of oratory, laden with references to revolutionary icons. True to form, the 10-minute speech, read from notes – in which the President spoke of the need for both sides to “learn the art of coexistence in a civilised manner” – was delivered in his usual deadpan style.

Though long hinted at as a possibility, Cuban-American rapprochement is still an about-turn – all the more unexpected among ordinary Cubans from a man who, though quieter and less bombastic than his charismatic, cigar-chomping brother, was once seen as the more ideologically rigid of the two.

When Raul took power, after Fidel fell ill, an insider who had met him described him in paradoxical terms as “ruthless and compassionate, as an executioner and as an executive, as a rigid Communist and a practical manager of economic and security matters”. It didn’t sound much like a reformer-in-waiting. Meanwhile, a retired US army commander who met both Castro brothers for talks in 2002 said that Raul’s real interest had been in “trading war stories”, adding, intriguingly, that while Fidel came across as obsessive, “Raul was interactive”.

Cuba’s one-party regime has outlived the collapse of the Communist order almost elsewhere else by a quarter of a century, seemingly without much effort. Whether it can continue to do so now that America is no longer the enemy is a moot point. Many Cubans are bound to start demanding bigger and faster economic and political reforms than Castro has allowed so far.

In pictures: Timeline of US and Cuba relations

Show all 19The question is how far can Raul bend. He is not a time-serving, adaptable bureaucrat of the type that flourished in the late-Communist period in Eastern Europe. He has spent his entire adult life acting as the right hand and disciple of his elder brother.

Aged only 22, in 1953, he took part by Fidel’s side in the first armed insurrection against the US-backed Batista regime, and, like Fidel, he went to jail for his role in the failed assault on the Moncada barracks. The two brothers headed into exile together and it was Raul who reportedly introduced Fidel to his new communist friend, Che Guevara. The trio returned together to Cuba in 1956 to restart the revolutionary war and the brothers rode together into Havana in January 1959, at the dawn of a new era.

From then on, until Fidel’s de facto retirement from politics as a result of illness in 2006, Raul was his brother’s helpmate – a quiet understudy, often dressed in the same military fatigues as Fidel, although without the latter’s trademark macho beard.

If Raul harboured the slightest doubts about his brother’s decision to take Cuba into the Soviet camp, changing what had been a left-wing but broadly based liberation movement into a monolithic, Soviet-style Communist Party – which is highly unlikely – he kept those doubts under wraps. In the meantime, he built up a formidable military reputation, commanding Cuban forces in two wars in Angola and one in Ethiopia. Significantly in terms of what has happened now, after the USSR withdrew its support, he was brutally pragmatic, sending his officers to business schools in Europe to learn about capitalist management techniques.

At the same time, the roles that members of Raul’s immediate family have undertaken in society and politics underscore the familial, dynastic nature of the regime. Not all the many members of the large Castro clan are on side, politically. His sister, Juanita, fled to America in the early 1960s, claiming that Fidel and Raul had together turned Cuba into a “giant prison surrounded by water”. One of Raul’s nieces, Alina, followed suit in the 1990s.

But the rest have slotted in nicely. Raul’s wife, Vilma, until her death in 2007, deputised for years as First Lady of Cuba after Fidel got divorced. One of his daughters, Mariela, is an MP and in charge of sex education, although her unorthodox views in favour of gay rights have raised eyebrows. A son-in-law holds a key position in the armed forces.

It is partly for that reason – because the Cuban system, like most Communist systems, rests in part on nepotistic networks that take the form of a kind of baronial class – that expectations of change were modest when Raul became President of Cuba in 2008.

That hunch has turned out to be largely correct, until now. Cuba under Raul did not follow the path taken by the leaders of Burma, another semi-closed authoritarian state that suddenly flung open its doors.

Cubans still cannot vote for the party of their choice. The economy remains almost wholly in the hands of state-run enterprises. Access to the internet is limited and censored. Where Raul has experimented – to a degree that Fidel would have blanched at – is with the planned economy. Elements of a free market have sprouted. Cubans may now buy and sell houses and cars and set up small businesses. The system of subsidised and rationed food is being done away with bit by bit.

The broader context of the great thaw between the US and Cuba is not the new freedom granted to small businesses or religion or even the release of aid worker Alan Gross, however, but the dawning realisation that the conflict is irrelevant in a world dominated by new and different conflicts. Castro’s own motives for seeking a breakthrough with America are a blend of the personal and political. The danger to him is not that the world has become more hostile to his beloved revolution but that it shrugs its shoulders. Cuba is no longer seen as a mentor in Africa, where national leaders have turned for ideas – and money – to China.

In Latin America, the newer left-wing governments are far friendlier to Cuba than the old generals were, but their sometimes patronising professions of respect don’t pay the bills. Venezuela bellows its fidelity to the ideological values of the Castro brothers, but Havana is beginning to see the alliance with that erratic regime as more of a liability than an asset.

Then there is the purely human matter of age. Last year, Castro announced that he intended to retire in 2018. By then he will 86 and the long reign of the Castro brothers will have come to an end. His concern now is to secure his legacy and that of his spectral-looking but still just about breathing brother.

“I was not chosen to be president to restore capitalism to Cuba,” he declared in 2013. “I was elected to defend, maintain and continue to perfect socialism.”

It seems a long shot, hoping an injection of investment cash from the world’s number one capitalist power will shore up one of the world’s last Communist states. The coming years will show whether Castro has played an ace, or a joker.

A life in brief

Born: 3 June 1931, in Biran, Cuba.

Family: Father was Angel Castro, a wealthy landowner. Mother was Lina Ruiz, a maid to Castro’s first wife.

Education: Attended Belen Jesuit Preparatory School, before taking a place at the University of Havana, though he failed to graduate.

Career: Played a central role in the Cuban revolution. Subsequently a respected military commander, and the right hand man of Fidel. President since 2006.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies