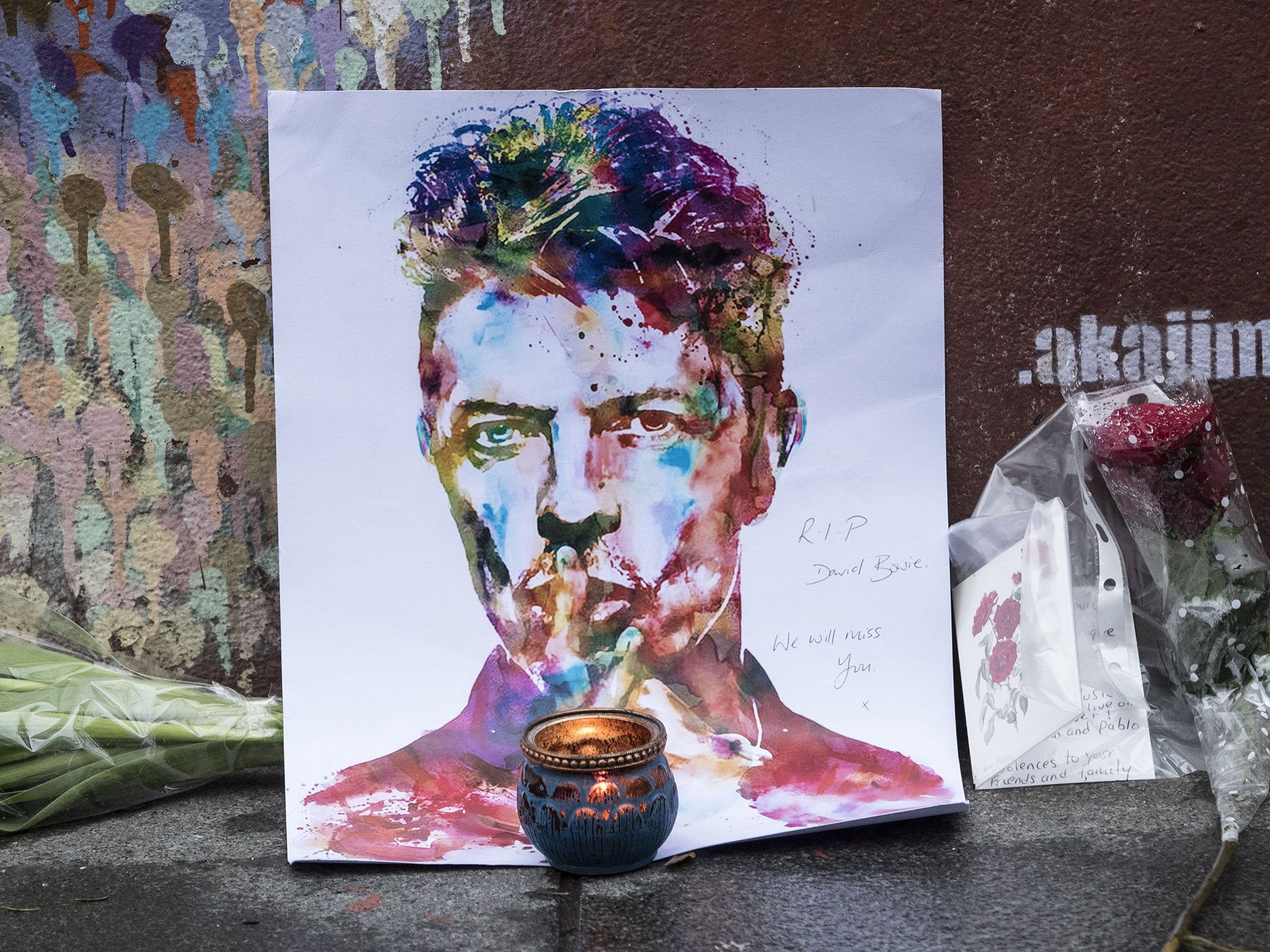

What the deaths of David Bowie and Princess Diana teach us about why we mourn in public

We live in a culture that repudiates death even as it is cultivated through public policy

The new year started with a sequence of very public losses. David Bowie, Alan Rickman, the husband and brother of Celine Dion, and most recently, Eagles’ guitarist Glenn Frey.

Some years ago, I collaborated to produce the book Mourning Diana. As a result, I have from time to time received requests to comment on the public response to the death of public figures. I have talked about the ways in which the passing of public figures and their mourning could stand in for more personal losses, or create moments of unexpected catharsis and identification with those things about which we cannot bring ourselves to speak, when they are close and touch us personally. We live in a culture that repudiates death even as it is cultivated through public policy – austerity is nothing if not a harbinger of social excommunication and lonely death. In public conversation, death is frequently discussed as an existential wrong (no child should die of …), or as “giving up”, or as a “lost battle”.

Brixton's David Bowie memorial street party

Show all 7But of late, I have come to have a new vantage point on these questions as they have taken a personal turn and I find myself in an odd parallel with Bowie – in human condition, if not in public prominence. Like him and many others, I have found a way to turn my own precarity into words and work, albeit in my case with a studied and distancing focus on culture rather than on myself. For example, following the conventions of my field, I immerse myself across multiple media in order to gain purchase on the tensions and flashpoints of the larger culture – cancer being one of my recent topics.

As part of this project, I collect, read and code every article about cancer that I find. Strangely, this activity gives me distance from my own situation. Similarly, my most recent paper concerns the pervasive iconography of the cancer patient as heroic warrior. I see this as a cult, an insistent fantasy, in distinction from the far less glamorous reality of those of us who survive it for a while, maybe for a long while, and of those who don’t. I’m not sure which one of those I’ll be personally.

I have found that I particularly like The Onion’s diabolically funny and contrarian treatment of the cancer culture – I find it bracing. I have greatly enjoyed Erin Gloria Ryan’s diatribes in Jezebel against the “pink crap” of the corporatised cancer industry. And I like Clive James’ dilemma that he has outlived his own death – and how awkward this is. I think I enjoy these examples because they don’t require me to mourn. Indeed, they assist me in the endeavour of not mourning. There is something about mourning that crosses a threshold, where one must re-imagine without oneself, as if it is me who dies, if I mourn a death.

Other articles I find more bothersome. Some are those written by doctors grieving their patients or family members grieving the loss of loved ones. With these, I find myself in a strange transference – identifying with those left behind, not the dying or dead themselves. Then there are the articles that announce or eulogise the death of public figures – a litany of deaths, relatively young, or perhaps not so young, but so vital in the public imaginary, that their loss strikes harder. These are public losses – people whose art or influence or even just name recognition mean that their departures leave a sudden, palpable, recognisable empty space.

When Diana died, the drama both evoked and sustained what was experienced by a great many as a sudden, shockingly evacuated space in the fabric of the public imagination. That she was so young was only part of it: that she was so pervasive was the other part. She had already been catapulted into a place of mourning through her extensive care for the lives of others. At the time, I theorised that this in particular attracted and generated the vox populi of personal loss. That this was a loss of not only a sympathetic public figure, but one who was spectacularly so. And as such, it was a death that both contained and exposed ineffable griefs and that made speakable the desire for a better society, for equality, for empathy, for common humanity.

The death of Bowie – which reportage suggests was not sudden for him – was nevertheless sudden for us. It was a death that followed on the heels of a birthday album. The release of this album, with its attendant rave reviews, presaged his next incarnation, his most recent reinvention in a career of amazing reinventions — it could not more forcefully have bespoken aliveness. And then suddenly, we were told he was gone.

Maybe it is that dramatically misaligned juxtaposition of aliveness against death that wrenches apart both the imagined intimacies and the structural distances between artists and their fans, or artists and their fellow artists, or public figures and publics. Some of the public mourning comes from those who, themselves part of the public realm, have lost a collaborator, a fellow artist, a history of sound and spectacle that informed their own in some way. Some comes from the multiple layers of fandom, those who intimately beloved a soundtrack of their earlier selves. And some comes from those, like me, who would not mourn ourselves if we could help it.

Deborah Lynn Steinberg, Professor of Gender, Culture and Media Studies, University of Warwick

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies