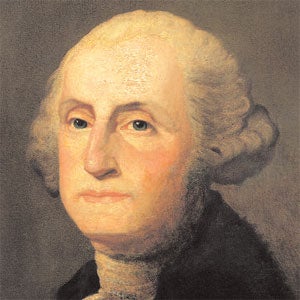

George Washington: The father of the nation

1st president - 1789-1797

How to deal with a saint? For a secular saint is what George Washington has become. History records him as the man who led American forces to victory in the War of Independence, and as the first President of the infant United States, who did more than anyone to ensure the success of an untried and unprecedented experiment in democracy. But in Washington's case, objective history more often than not takes a back seat to myth.

His name is everywhere. His face adorns the dollar bill and the 25 cents coin. Across the modern US, 26 mountains are named after him, as well as 740 schools, a dozen colleges and universities, 155 towns and counties, various bridges, parks and forts; not to mention an entire state of the union and the very capital of the country he did so much to found. The only other world capital to share the distinction with Washington DCis Monrovia, named after the fifth President, James Monroe, who created Liberia as a home for freed slaves.

Washington often seems as remote as a saint, a half-mythologised figure from distant antiquity. And indeed, this stern-looking white Virginian in clasped hair and frock coat, dead for more than 200 years, would seem to have little to do with the teeming, multicultural superpower of today; about as relevant to the contemporary United States as the Emperor Augustus is to modern Italy. Everyone pays lip-service to George Washington, but few people have much idea of the human being behind the symbol.

Nor did his wife Martha greatly aid the historian's cause, destroying almost entirely the correspondence of 40 years of marriage that might have given posterity a truly unvarnished portrait of the man. Her action was understandable enough, to preserve her privacy and relationship with a man who by the end of his life had become America's first mega-celebrity, on whom the mantle of divinity was already descending. Anything connected with him – a pen, a stirrup, even a fragment of his nightgown – was treated as reverently as a holy relic.

Nor did the early chroniclers help. For Parson Weems, the first of Washington's countless biographers, his subject was "a hero and demigod... the greatest man who ever lived". In his The Life of Washington, published in 1800, a year after the first President's death, Reems described him as "just as Aristides, temperate as Epictetus, patriotic as Regulus, modest as Scipio, prudent as Fabius, rapid as Marcellus, undaunted as Hannibal, as Cincinnatus disinterested, to liberty firm as Cato, as respectful of the laws as Socrates".

And what Reems didn't know, he made up; thus the tale of the cherry tree. The six-year-old Washington is said to have been given a hatchet and, as young boys are wont to do, he went around chopping at everything in sight. Alas, he destroyed a lovely young cherry tree in the garden. His father noticed, and asked young George if he knew what had happened. The future President paused only a second before answering: "I can't tell a lie, Pa, I did cut it with my hatchet." At which point his father embraced him, saying that "such an act of heroism is worth more than a thousand trees, though blossomed with silver and their fruits of purest gold".

In Washington's case, therefore, the first draft of history is not very helpful. Nor is the other item of trivia about him, as well-known as the tale of the cherry tree (though this one happens to be true). Washington had appalling teeth. By the time he became President in 1789 he had only one tooth left, and one of his many sets of dentures is on permanent display at his estate at Mount Vernon. But once you move beyond the trivia and set aside the legends, a truly remarkable man none the less emerges – in some ways as relevant to 21st-century America as he was to the fledgling late 18th-century republic.

A fourth generation Virginian, George Washington was born in 1732. His father Augustine, a tobacco farmer, died when he was 11, and George's education was modest. But he quickly developed a taste for adventure and the outdoor life.

The history of America, and the world, could have been very different had his domineering mother, Mary, not forbidden him to become a midshipman in the British navy, a position that had been arranged by the powerful Fairfax family – Virginia landowners and vital patrons of Washington. Undeterred, the Fairfaxes gave him another job, as a surveyor on a trip to establish the boundaries of their vast estates in what was then America's inland wilderness. In 1749, at the age of only 17, the future President gained his first public office, as a surveyor for Culpeper County. He spent most of the next three years surveying Virginia's frontiers, and learning the rugged outdoor skills that he would later call on as a soldier.

On the death of his brother Lawrence in 1752, George inherited the estate at Mount Vernon, on the Potomac estuary 15 miles south of present day Washington, which would be his true home for the rest of his life. By then he was an arresting figure, slender, exceptionally tall for the period at 6ft 2in, and an outstanding horseman. However, most crucially for US history, he took over Lawrence's position as a major in Virginia's militia – again at the instigation of the Fairfax family. Thus began Washington's career in soldiery that would culminate in victory at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781, sealing American independence.

But it was during an earlier war that he learnt the skills of battle. In 1753, the 21-year-old Washington was an obvious choice of Virginia's governor to lead an expedition to warn off the French, who had moved south from Canada to build forts along the Ohio river on land claimed by Britain.

The following year, what became known as the French and Indian War began in earnest. Washington led a force of 160 men west and staged a surprise attack on a French unit. But that victory – which the French claimed was an unprovoked assault – drew a ferocious counterattack from the enemy, leading to humiliating surrender at Fort Necessity. It was Washington's first taste of defeat. But as in the Revolutionary War against the British two decades later, setbacks only seemed to make him stronger.

He emerged with honour from the disastrous Braddock campaign mounted by the British in 1755 in a second attempt to drive the French from the Ohio valley and in 1756 was named commander-in-chief of all Virginia's forces – he was only 24 at the time. By now an expert in the stealthy and improvised form of warfare needed in the forests of the American wilderness, Washington led the expedition to capture the strategically vital Fort Duquesne in 1758. Five years later, the French had abandoned all claims to lands east of the Mississippi, and the war was won.

In 1758, Washington returned to civilian life and for the next 16 years led his preferred life of a gentleman-farmer at Mount Vernon. His marriage to the wealthy widow Martha Dandridge Custis made him one of the richest planters in Virginia. In 1759, his political career began as he was elected to Virginia's assembly, the House of Burgesses, where he would serve until 1774, alongside the likes of Thomas Jefferson and Patrick Henry.

All the while, however, confrontation was growing between the colony and its ultimate ruler, Britain, over the issue of taxation. Washington was proud of his English heritage, but no less outraged than his fellow citizens by London's new policy of making the colonies help pay for war debts and for their continued defence, without according them the slightest say in decisions that affected them.

In 1769, Washington emerged as a leader in the resistance movement, when he proposed to the Virginia assembly a colony-wide boycott of British goods. Britain gave some ground, but the underlying tensions grew and exploded with the Boston Tea Party of 16 December 1773. The British navy blockaded the port of Boston in reprisal, while the colonies – regarding a move against one as a move against all – convened the first Continental Congress to protect their rights. Like most others in the Virginia delegation, Washington was all but convinced that the only solution was independence.

Events then moved fast. By the time of the second congress in 1775, fighting had broken out in Massachusetts, and Boston was occupied by the British military. War in the north was under way; the only question was who would lead the colonial forces. To lock the southern colonies into the struggle, it was argued, a southern commander was essential. Washington, who had broad military experience and first hand knowledge of the British army, was the obvious choice.

The new commander-in-chief of the Continental Army took charge of a ragtag militia of 16,000 men on 3 July 1775. The war, America's longest conflict until Vietnam, would drag on for eight years. There were moments when all seemed lost, but the war would end in victory and the birth of what would become the richest and most powerful country in history.

Nowhere is the disentangling of myth from reality over Washington more important than in assessing his record as a general. For admirers, he ranks alongside Hannibal, Caesar and Napoleon as one of history's greatest commanders. In terms of his influence on history, that status might be justifiable. Undoubtedly too he was a gifted organiser and administrator, a born leader of enormous personal bravery who bowed to no setback and turned what was little more than an armed rabble into America's first regular military force. As a strategist, however, his record is mediocre. America probably would not have won its independence without Washington, but a more skilled, less cautious battlefield commander could surely have won it more quickly.

At first the war went badly for the colonies. In November 1776, the British drove Washington's forces from New York. Without the spectacular victory at Trenton, after Washington's force had crossed the half-frozen Delaware river on Christmas night, the war effort might have collapsed entirely.

Washington quickly secured another victory at Princeton, driving the British from New Jersey. By September 1777, however, he was reeling again, with the defeats of Brandywine and Germantown, and the British capture of Philadelphia. Exhausted, demoralised and desperately short of supplies, his men set up winter quarters at Valley Forge in Pennsylvania. Somehow, Washington rebuilt his force, in what was perhaps the turning point of the entire war. The Continental Army that re-emerged to take the field in June 1778 was no longer a collection of ill-trained state militias, but the first true American army.

The conflict dragged on, but with the gradual entry of the French into the fray, the balance of power shifted. The Continental Army faced other perilous moments. But in October 1781 General Cornwallis and his army, trapped at Yorktown between the forces of Washington and Lafayette by land and a French fleet by sea, were forced to surrender. In 1783 the Treaty of Paris was signed, the last British troops left New York for home, and the United States of America was an internationally recognised country at last.

For a second time, Washington went home to his beloved Mount Vernon. But not before he had headed off the Newburgh Conspiracy of 1783. The episode, when officers who had been unpaid for months were plotting to take power from Congress, was the closest the US has ever come to a military coup. The address with which Washington quelled the uprising was one of his finest moments, underlining once more his belief in the supremacy of civilian over military power.

But his retirement lasted only four years. It quickly became clear that the Continental Congress and the existing Articles of Confederation between the states were utterly inadequate; without the glue of war to hold it together and submerged in war debt, the country threatened to disintegrate into its 13 component parts unless an effective central government was created. In 1787, the Constitutional Convention began in Philadelphia. Washington the war hero, the most famous man in the country, was the obvious choice to preside over it. And although he might not have liked the idea, he would almost certainly be the first President.

However noble the new constitution's goals, however deftly engineered the separation of powers, and the checks and balances between the three branches of government, it was ultimately no more than a piece of paper, untested in real life. Washington did more than anyone to turn a document into a functioning polity, combining a strong central government with the jealously guarded rights of the 13 individual states.

As case after case before the Supreme Court proves, conflict between these two objectives continues to this day. But it was never more visible than in Washington's first term between 1789 and 1793, in the rivalry between two brilliant colleagues: Thomas Jefferson, then Secretary of State and champion of states' rights, and Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury and leader of the Federalists. Ultimately, Washington, convinced that without a strong central authority the infant country would fall apart, sided with Hamilton. The price was an estrangement from Jefferson that endured until his death.

Washington was all too aware of the burden on his shoulders. "I walk an untrodden path," he wrote soon after taking office. "There is scarcely any part of my conduct that may not hereafter be drawn into precedent." In fact, he literally invented the modern presidency.

He instigated the cabinet (albeit consisting then of just four persons, the secretaries of state, treasury and war, and an attorney general, compared with the two dozen or so posts of cabinet rank today). Under Washington, the basic model for relations between the presidency and Congress emerged, as did the tradition that a president takes the lead in foreign affairs.

It was Washington who established the precedent that a president should serve no more than two four-year terms. In truth, he had intended to retire after only one, but Hamilton and Jefferson alike pleaded with him to stay on in the interests of national unity. "North and South will stay together if they have you to hang on," Jefferson wrote to him. But in 1797, Washington left power for good, and his two-term precedent endured, with the sole exception of Franklin Roosevelt (after whose death the two-term limit was finally written into the constitution).

Washington even established the title of his office. He had resisted overtures to become king, but others pressed even more bombastic designations. "His Highness the President of the United States of America and Protector of Their Liberties," was one suggestion, "His Exalted High Mightiness" was another. At Washington's request, it was decided he should be called simply the President of the United States, or "Mr President".

Less happily, he presided over the emergence of some other enduring traditions of American government. One was infighting among senior aides, of which the rift between Hamilton and Jefferson was an early forerunner. Another was that of a troubled second term. Between 1789 and 1792, Washington put barely a foot wrong. But after being unanimously re-elected in March 1793, he was quickly confronted by a devastating national health crisis, a home grown tax revolt that briefly threatened a second revolution and, above all, by a huge foreign crisis.

The storming of the Bastille in 1789 and the revolt against overweening monarchical power was one thing, a tribute to the ideals of the American Revolution a decade earlier. The descent of the French Revolution into the Great Terror, and the spectre of a new war between France and Britain in which the young United States would be forced to take sides, were quite another. Jefferson's sympathies, and those of the public, lay with France. Washington and Hamilton, however, believed that a new war with Britain that at the least would cut off trade with Europe, and at worst might destroy a still fragile country, simply could not be risked.

Jefferson resigned in December 1793, and the following year Washington began negotiations on a treaty with Britain. The deal that emerged was widely seen as a sell-out to the former colonial master, and the President was vilified by the Jeffersonian press. It was an early lesson that in a democracy, government involves tough choices. Washington had paid a heavy price in popularity, but he had bought vital time for the new country to find its feet.

Domestic crises arose as well. In the summer of 1793, the capital, Philadelphia, was swept by yellow fever, perhaps the deadliest epidemic in US history. The city was all but evacuated, but only the onset of winter ended the mosquito-born epidemic. The following summer, mobs in western Pennsylvania took to the streets in protest at a new government tax on whiskey. Briefly the 6,000-plus protesters threatened to secede, and the "Whiskey Rebellion" only ended when a 13,000-strong federal army was mobilised against them. Washington himself commanded the force, the only time in US history that a president has led his troops in person.

Somehow, too, he found time to supervise the construction of the new national capital that would soon bear his name. Washington DC was laid out by the French architect Pierre L'Enfant but, as befitted a former surveyor and lifelong freemason, the first President kept an eagle eye on developments. He laid the cornerstone of the Capitol building in person in 1793, and closely monitored the construction of the White House (completed in 1800, a year after his death).

However, he conspicuously failed to solve one problem – America's original sin of slavery. He himself had been a slave owner since 1743, when he inherited 10 from his father. As he grew older, he appears to have personally turned against the practice, above all because of the contradiction with the ideals of liberty and equality in whose name the Revolutionary War was fought.

He kept the issue out of the new draft constitution, knowing full well it might tear the country apart at its birth. A letter to his nephew from 1797, the year he returned for the last time to Mount Vernon, was prophetic. "I wish from my soul that the legislature of this state [Virginia] could set the policy of a gradual abolition of slavery," he wrote. "It would prevent much future mischief."

When he died in 1799, Washington owned 316 slaves. In his will, he called for them to be given their freedom, after the death of his wife Martha, but she carried out his instructions while still alive, in 1801. Sixty years later, the US was plunged into a civil war over slavery – mischief that almost destroyed the country, just as Washington had feared.

Even from these bare bones of his life, two things are plain about George Washington. First, he was an undeniably great man. Like every human being, he had flaws. His own included a fierce temper, which he gradually learned to control. As a young man he could be excessively driven and ungracious. As noted earlier, he had shortcomings as a battlefield commander. Whether as general or president, he could be reserved and distant.

Nor was he the most intellectually gifted member of the extraordinary group of men who founded America. Washington had a good, but not a great mind, according to Jefferson (who had no doubt that his own intellect fell into the latter category), and was no more than an adequate communicator. "His colloquial talents were not above mediocrity," in Jefferson's words, "possessing neither copiousness of ideas nor fluency of words." Then again, such gifts probably mattered less then than they do now. Washington may also have been hampered by his poor teeth – which could explain his clenched-mouth and slightly pained appearance in the famous portrait by Gilbert Stuart that adorns the dollar bill.

But his personal bravery was astounding. As Jefferson put it: "He was incapable of fear, meeting personal dangers with the calmest unconcern." In public life he was solid and unflappable and, as his contemporaries all testified, possessed an enviable judgment of both men and events. The combination made him a born leader. Washington was the man to whom his peers instinctively turned to in a crisis.

For Abigail Adams, the wife of Washington's successor John Adams, his defining quality was his unaffected dignity. "The gentleman and the soldier are agreeably blended in him," she wrote. "Modesty marks every line and feature of his face."

Washington was never vain. Probably no great leader has coveted power less and none has been less corrupted by power. He had none of the haughty sense of destiny possessed by, say, General de Gaulle – the iron belief that a desperate country would come to him on bended knee, and that he would dictate the terms on which he accepted the summons of history.

Not once, but three times Washington walked away from power: in 1759 (in Virginia), in 1783 (after the war) and in 1797. His election as President was no triumph to gloat over, but "the event which I have long dreaded". The news, he said, left only "a heart filled with distress" as he contemplated the "ten thousand embarrassments, perplexities and troubles to which I must again be exposed".

In that sense, Washington is the role model for every one of the 42 presidents who have followed him – even though his example has usually been honoured in the breach. No country cherishes its legends quite like the US, but the accounts of contemporaries such as Abigail Adams have no need of embellishment by the likes of Parson Weems. Washington's record speaks for itself.

After he left the presidency in 1797, he was the most famous private citizen on the planet. His death two years later plunged the young nation into grief, and the funeral ceremonies and commemorations of his life continued for months afterwards. "First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen," was the famous phrase of Harry "Light Horse" Lee, Washington's old comrade-in-arms from the Continental Army, and later governor of Virginia. Or as the assembled members of the Senate put it in a note to Washington's successor, John Adams: "Our country mourns its father."

The second, even more salient fact about Washington is that without him the country might not have existed. And even if it had, it might have quickly disintegrated into its component parts or fallen victim to a military coup, had not Washington's hand been at the tiller.

Today, the position of the US as an economic, military and cultural colossus is taken for granted. It is easy to forget how precarious its birth was. In 1776, there was no guarantee the newly proclaimed country would win the war. That it prevailed was due in large part to Washington's powers of leadership.

But winning the war was only the start. The United States that had won independence was broke and in semi-chaos. It had to work out how to govern itself and – more importantly – put that system into practice. Without Washington's guidance of the Constitutional Convention, and the open secret that he would be the first president, that task too might have proved impossible.

Today, George Washington does not overly impinge on the American consciousness. Biographers and historians have turned their focus to the other founding fathers: Adams, Hamilton and Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and James Madison. But, without Washington, these undeniably great men could have been mere footnotes of history.

And if you seek Washington's monuments, look around. Not just at the physical ones – from the eponymous obelisk that rises sword-like from the heart of the country's capital, to the face on Mount Rushmore, to all those towns, counties, roads, schools, hills and mountains across the continent that bear his name – but to the intangible ones as well. Each year, for instance, the US celebrates President's Day on the third Monday of February. The holiday was designated Washington's Birthday (22 February according to the modern calendar, 11 February by the Julian calendar in use when he was born), and was first celebrated in 1796, when he was still president.

Meanwhile, Washington's Farewell Address of September 1796, a few months before he returned to Mount Vernon for good, ranks second only to Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address in the canon of sacred presidential texts. Never delivered orally but published in every newspaper, the text is as relevant today as when it appeared more than two centuries ago.

In it, the departing president offers a stirring defence of federal government, and warns against excessive partisanship in politics. Though Washington never wore his faith on his sleeve, the Farewell Address stresses the importance of religion as a basis for personal morality, without which no society can function. In words that ring especially true right now, he argued for stable credit and the avoidance of "the accumulation of debts". Revenue was needed to pay debts, but "to have revenue there must be taxes... and no taxes can be devised that are not inconvenient and unpleasant."

Not only did Washington anticipate by five years Jefferson's famous warning about the perils of "entangling alliances" (the phrase used in the address was "permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world"). A century and a half before Dwight Eisenhower spoke of the danger of a "military-industrial complex", Washington was also urging his fellow citizens to avoid "overgrown military establishments" that were "inauspicious to liberty".

America's devotion to its military may be traced back to Washington, the first of a number of presidents to have served as generals, of whom Eisenhower is but the most recent. None, however, more perfectly fused military and political service to his country. Washington's example helps explain why generals often are touted as, and sometimes become, presidential candidates. The former Nato commander Alexander Haig in 1988, Colin Powell in 1996, retired general Wesley Clark in 2004 and, who knows, maybe David Petraeus in 2012 – every soldier who runs for the White House hopes that Washington's stardust will land on their shoulder, that they will be seen as another citizen-warrior, as wise, as honourable and as impartial as the first president.

In the meantime, each year the entire text of the 1796 Address is read aloud on the floor of the Senate and entered into the Congressional record – another reminder of the giant shadow cast by George Washington over America's political history.

He remains that most tantalising of figures, as appealing in our anxious times as 200 years ago: the national leader who rescues his country, but who would rather be anywhere than in the political arena. Not surprisingly, Washington was the first president of the Society of the Cincinnati, founded in 1783 to preserve the ideals of the War of Independence and named after Cincinnatus, the 5th century BC Roman leader who agreed to serve as dictator during a war, but after victory immediately returned to his plough.

In Washington's case the parallel was unmistakable, except perhaps in two respects. By the 1790s he was one of the biggest landowners in America, and his Mount Vernon estate was not so much a farm as an agro-industrial conglomerate of its day, boasting a large fishing operation in the Potomac estuary, large grain production, and the biggest whiskey distillery in the country. And while Cincinnatus was away for mere weeks, Washington's absences were measured in years.

Today, Washington is unanimously ranked as one of the three great presidents in American history, a blue chip in the fickle stock market of presidential reputations. The "father of his country" is in the exclusive company of Lincoln, who won the Civil War, and Franklin Roosevelt, who led the US through the Great Depression to victory in the Second World War.

He may be out of fashion in the academic world, but not with the public, who flock to Mount Vernon every day of the year, shuffling like pilgrims through the house itself, inspecting the fabulous new museum, and savouring the handsome grounds and magnificent views across the Potomac estuary.

These visitors may not believe in holy relics. They realise the great man never actually cut down a cherry tree and did not voluntarily confess all to his father, but they do know he was the man who did more than anyone to ensure the success of the world's most ambitious experiment in democracy.

And at a moment when America's image is more tarnished than it has been for many decades, the person of Washington – real or imagined – is surely more precious than ever.

In his own words

"My movements to the chair of government will be accompanied by feelings not unlike those of a culprit who is going to the place of his execution."

"Precedents are dangerous things; let the reins of government then be braced and held with a steady hand, and every violation of the Constitution be reprehended: if defective let it be amended, but not suffered to be trampled upon whilst it has an existence."

"As the sword was the last resort for the preservation of our liberties, so it ought to be the first to be laid aside when those liberties are firmly established."

"Labour to keep alive in your breast that spark of celestial fire called conscience."

In others' words

"First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen." Henry Lee.

"One of the greatest captains of the age." Benjamin Franklin

"You commenced your Presidential career by encouraging and swallowing the greatest adulation, and you travelled America... to put yourself in the way of receiving it... As to what were your views... they cannot be directly inferred from expressions of your own... As to you, sir... a hypocrite in public life, the world will be puzzled to decide whether you are an apostate or an imposter, whether you have abandoned principles or whether you ever had any?" Thomas Paine

"Too illiterate, unread, unlearned for his status and reputation." John Adams

Minutiae

Washington's presidential salary was $25,000 – equivalent to around $1m today. He spent around seven per cent of this on alcohol.

He was the only president to be inaugurated in two cities: New York City and Philadelphia.

His favourite recreations were billiards, cards and foxhunting.

He struggled for many years with the unsatisfactory dentures of the day, made not (as is often believed) of wood but, rather, from a variety of other unlikely substances, including lead, ivory, cows' teeth and hippopotamus bone. The latter proved excessively porous and was stained black by the port he drank.

The story about the cherry tree was entirely imaginary – made up soon after his death by his biographer, Parson Mason Locke Weems.

George Washington was the only president to be elected unanimously.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies