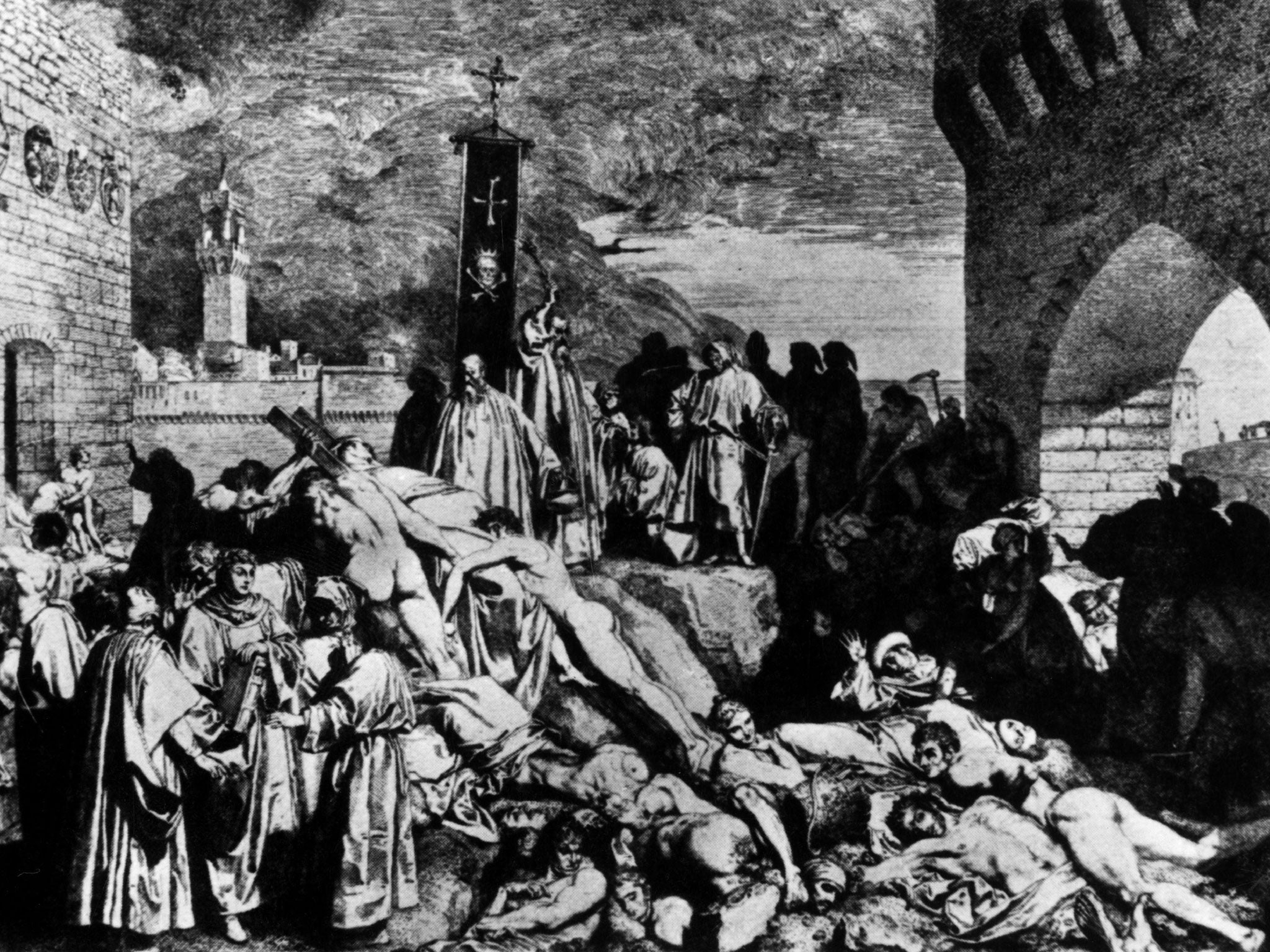

The Black Death: Plague that killed millions is able to rise from the dead

Black rats are also implicated in both outbreaks, which took place 800 years apart

Two of the most devastating outbreaks of plague in history, each of which killed more than half the population of Europe, were caused by different strains of the same infectious agent, a study has revealed.

The Justinian Plague of the 6th Century AD, which is credited with leading to the final demise of the Roman Empire, and the Black Death of the 14th Century, were both caused by the independent emergence of the plague bacterium from its natural host species, the black rat, scientists said.

An analysis of bacterial DNA extracted from the teeth of two plague victims who died in the early 6th Century in present-day Bavaria, Germany, has shown that they were infected with the bacterium Yersinia pestis, the same plague agent known to have caused the Black Death 800 years later.

However, a detailed comparison of the bacteria’s DNA sequences has revealed that the two outbreaks were quite independent of one another. Each pandemic was the result of different Yersinia strains, indicating the independent emergence from the black rat on two separate occasions, the researchers said.

Although the strain behind the Justinian Plague died out completely, the strain that caused the Black Death probably re-emerged a few centuries later to cause the so-called Third Plague pandemic which began in the mid-19th Century in China and went on to kill about 12 million people in China and India alone, although it did not travel to Europe.

The scientists behind the study, published in the journal The Lancet Infectious Diseases, warned that the findings suggest there is a possibility of another pandemic strain of plague to emerge from the existing reservoir of Yersinia bacteria living in the current rodent population.

“The key point here is that this bug can re-emerge in new forms in humans and can have a tremendous impact on human mortality. It’s done it three times in the past and we should be monitoring it for the future,” said Hendrik Poinar, director of the Ancient DNA Centre at Canada’s McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario.

The Justinian Plague, named after the Roman emperor who died of it, probably began in Asia but first came to prominence when it swept through the eastern Roman capital of Constantinople. It killed at least 50 million people, almost half the global population at the time, and is generally regarded as the first documented outbreak of bubonic plague.

The DNA analysis of the full Yersinia genome extracted from the two Bavarian plague skeletons, however, has shown that the pandemic died out completely within a couple of centuries without leaving any bacterial descendants, Dr Poinar said.

“The research is both fascinating and perplexing. It generates new questions which need to be explored, for example why did this pandemic, which killed somewhere between 50 and 100 million people die out?” Dr Poinar said.

The scientists extracted overlapping fragments of Yersinia DNA from the teeth of the two plague victims and were able to build the entire genome of 4.6 million “base pairs” – the individual letters of the genetic alphabet that comprise the bacterium’s genetic code.

“We know the bacterium Y. pestis has jumped from rodents into humans throughout history and rodent reservoirs of plague still exist today in many parts of the world,” said Dave Wagner of Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, Arizona, the lead author of the study.

“If the Justinian plague could erupt in the human population, cause a massive pandemic, and then die out, it suggests it could happen again. Fortunately, we now have antibiotics that could be used to effectively treat plague, which lessens the chances of another large scale human pandemic,” Dr Wagner said.

Long periods of warm, wet weather preceded both the Justinian Plague and the Black Death, which was thought to have resulted in an explosion in the rat population. Scientists suspect that plague outbreaks eventually die out as people develop a natural immunity to the bacteria.

“Another possibility is that changes in the climate became less suitable for the plague bacterium to survive in the wild,” Dr Wagner said.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies