Ruling on stem-cell patents may spell end of research in Europe

A fledgling biosciences industry that promises to revolutionise medicine in the 21st century could be destroyed by a French judge who has declared it immoral to patent inventions based on cells derived from human embryos.

Some of Britain's leading biomedical scientists – including Sir Ian Wilmut who cloned Dolly the sheep – have expressed their horror over a legal opinion by Yves Bot, advocate-general of the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg, that no one should be allowed to patent any invention that comes out of research involving stem cells obtained from human embryos. This would include potential treatments for incurable conditions ranging from heart disease and Parkinson's to blindness and spinal cord injuries.

Sir Ian and 12 other leading stem- cell researchers said the ruling – if followed by the judges of the European court – would effectively end all research on embryonic stem cells, which have the unique ability to develop into any of the dozens of cell types that make up the human body.

"Work on human embryonic stem cells is just completely undermined by this [legal] opinion," Sir Ian said yesterday. "The consequences, if it was not possible to patent these processes, is that companies would be much less likely to invest in academic research if they were not allowed to protect their inventions."

Mr Bot, a magistrate considered to be on the right of Nicolas Sarkozy's conservative party, was required by the European Court to make a ruling on a dispute that has dragged on through the German patent courts. In his legal opinion, he says that stem cells derived from human embryos have the ability to "evolve" into a complete human being and should therefore be legally classified as embryos. This would prohibit them from being used in patent applications.

"To make an industrial application of an invention using embryonic stem cells would amount to using human embryos as a simple base material, which would be contrary to ethics and public policy," said a court statement.

"The advocate-general considers that an invention cannot be patentable where the application of the technical process for which the patent is filed necessitates the prior destruction of human embryos for their use as base material, even if the description of that process does not contain any reference to the use of human embryos."

Professor Austin Smith, chair of the Welcome Trust Centre for Stem Cell Research at Cambridge University, said that banning patents would effectively remove the protection of intellectual property and lead to the abandonment of vital research into a host of incurable diseases.

"This opinion by the advocate-general is threatening and undermining to our research and to European research in general. Patenting is a key vehicle for the translation [of university research] to deliver new products for medicine," Professor Smith said.

"If the European Court were to follow this opinion, the reality is that all patents in Europe that involve human embryonic stem cells will be dissolved in Europe. This will wipe out the European biotechnology industry in this area."

The 13 Grand Chamber judges of the European Court of Justice will consider M. Bot's opinion over the coming weeks and are expected to make a final ruling on whether to ban past and future patents within six months.

Professor Pete Coffey, a stem-cell scientist at University College London who is hoping to start a clinical trial to treat age-related macular degeneration – a form of blindness, said that the effects of a ban on patents would lead to British inventions being exploited in the United States and other countries where patents are protected.

The British governmentwas spending millions of pounds trying to establish links between UK universities and pharmaceutical companies interested in developing therapies based on human embryonic stem cells. All this would be jeopardised if patent protection were banned in Europe, he said.

"It's going to have a major impact in the UK's economy... it will hit industry enormously."

Uses for stem cell therapy

Blindness British scientists are hoping to begin clinical trials using stem cells that can develop into the light-sensitive cells at the back of the eye, which degrade in age-related macular degeneration. Scientists in the US are closer to using the cells to treat another form of blindness, Stargardt's Macular Dystrophy.

Spinal cord injury American biotechnology company Geron has begun the first clincial trial of human embryonic stem cells to treat spinal injury. The cells will be injected into patients' spinal cords, hopefully to restore lost nerve function.

Parkinson's disease Scientists hope to develop a laboratory model of certain diseases, such as Parkinson's, using stem cells derived from patients with the condition. In this way, they hope to create laboratory "models" of the disease based on human cells, which can be used for testing new drugs and treatments.

Heart disease Ultimately, the aim of stem cell therapy is to be able to mend damaged tissues in situ, rather than replacing a whole organ. Heart disease, for instance, could be tackled by injecting stem cells into the damaged site and allowing them to re-populate the damaged area of the organ. This would in theory be safer, cheaper and easier than carrying out a whole-organ transplant operation.

Steve Connor

Q&A: How this law could block the work of scientists

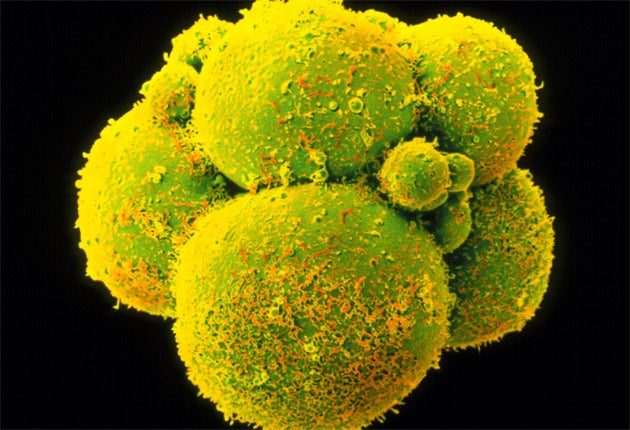

Q. What are embryonic stem cells?

These are cells derived from a very early human embryo, usually only three or four days after conception by IVF. They can be coaxed in the laboratory to develop into any of the cells found in the human body. Scientists hope to use them in revolutionary techniques, such as for testing new drugs or for transplant operations to replace damaged tissue.

Q. Why do scientists need to patent these inventions?

In order to encourage pharmaceutical companies to spend the millions of pounds necessary to develop a university project into a safe clinical technique, scientists need to ensure their intellectual property is protected.

Q. Why is this suddenly an issue?

It began with a court case in Germany when Greenpeace sued a Bonn University scientist, Oliver Brüstle, who held a patent on a technique involving embryonic stem cells. The court case went against Dr Brüstle and he appealed to a higher court, which referred it to the European Court of Justice, which asked its advocate general, Yves Bot, for his legal opinion on whether such patents should be allowed. M. Bot has just given his opinion, saying that patents involving human embryonic stem cells should be banned.

Q. Does this legal opinion matter?

The 13 judges of the Grand Chamber of the European Court will now consider their advocate general's opinion. If they uphold it, all existing patents will be dissolved if they involve human embryonic stem cells. Scientists said this would be disastrous for the fledgling stem-cell industry because drug companies would flee to other countries where their intellectual property can be protected in law.

Q. Can't the UK just ignore the European Court?

No, the decision of the court is binding on member states.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments