What has the Mars Curiosity rover actually achieved in its first year on the Red Planet?

It has been roaming the Martian surface for exactly a year. So what have we learnt from its incredible journey?

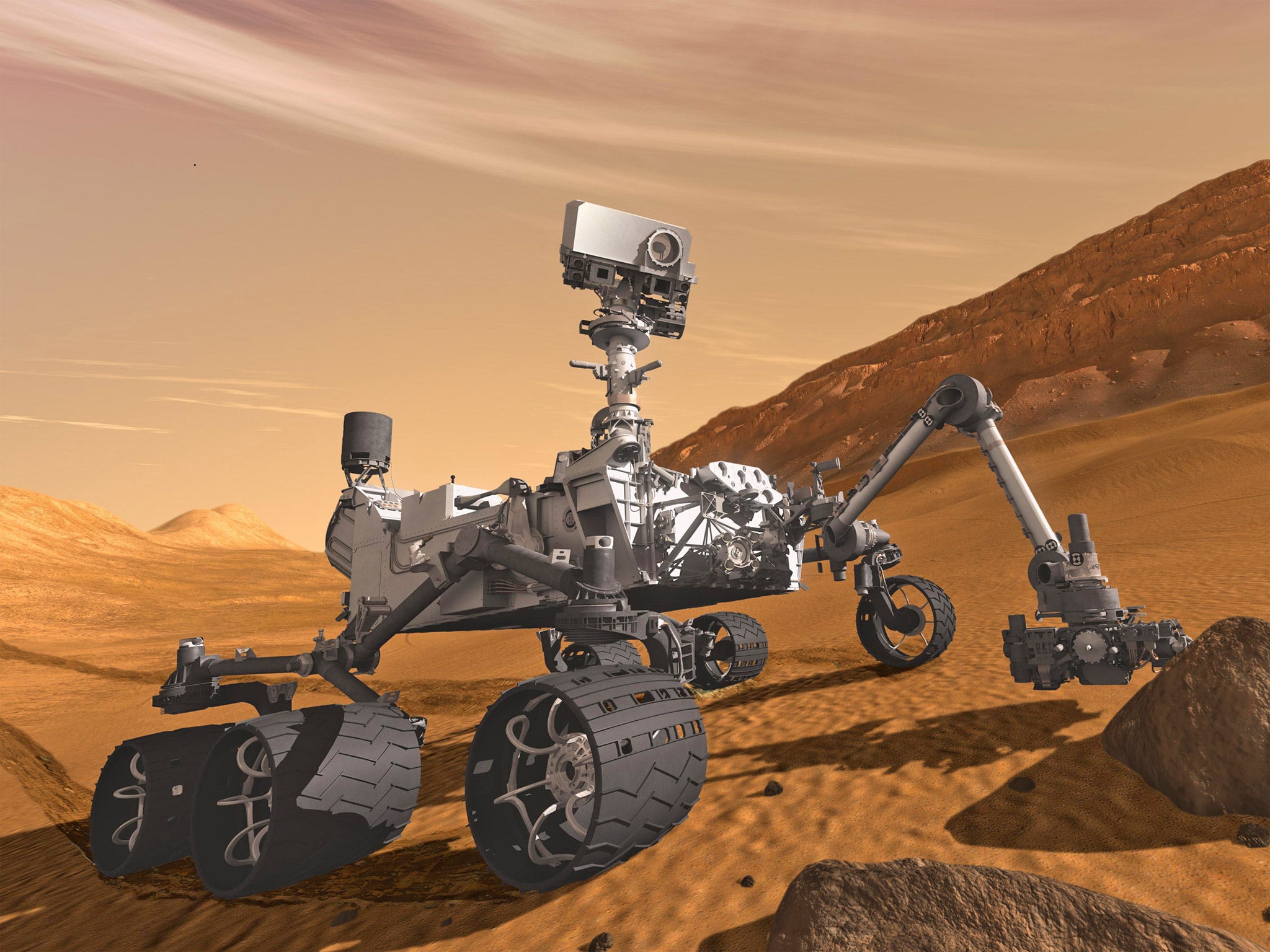

Of all the space probes and landers that have been sent to Mars over the past four decades, none has matched up to the extraordinary sophistication – and size – of the Curiosity rover, a six-wheeled robotic vehicle and mobile laboratory the size of a large family car.

Click HERE to view graphic

It will be a year and a day on Wednesday since Curiosity made its remarkable and unprecedented descent into the Gale Crater of the Red Planet. Because of its size and weight – ten times as massive as previous rovers – landing with conventional parachutes and airbags posed a problem.

So, scientists came up with radical idea of hoisting Curiosity down gently on nylon tethers from a retro-rocket propelled “sky-crane” hovering overhead. Nothing like it had been attempted before and yet the entire “seven minutes of terror”, which involved braking from a speed 13,200mph at the spacecraft entered the Martian atmosphere, went without a hitch.

As John Holdren, senior science adviser to President Obama, remarked at the time: “The successful landing of Curiosity marks what is really an unprecedented technological tour de force.”

Yet the expectations of what Curiosity could achieve were even higher, according to Pete Theisinger, the project manager. “We have the possibility of just monumental science accomplishments,” he said at the start of the two-year mission.

Some of those expectations have already been met. For the past 12 months Curiosity has collected 190 gigabits of data, returned more than 36,700 full-sized images of Mars to Earth, fired more than 75,000 laser shots to analyse the Martian air and soil, and provided a detailed chemical signature of two samples of rock.

Half way through its mission, Curiosity became the first rover to drill into Martian rock and lived up to its name by satisfying one of the biggest mysteries of Mars – could the planet ever have supported life? The answer, according to the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Nasa), is an unequivocal “yes”.

Ancient Mars would have had the right chemistry to support life. Curiosity found carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and sulphur – the key organic elements necessary for life on Earth – and, most crucially of all, there was once abundant running water on the surface of the Red Planet, said John Grotzinger, the project scientist.

“We have found a habitable environment that is so benign and supportive of life that probably if this water was around and you had been on the planet, you’d have been able to drink it,” Dr Grotzinger said.

Barely two months after it landed, at the end of last September, Curiosity found the first direct evidence that Mars once had a network of fast-moving streams. Smooth and rounded rocks, just like the water-eroded pebbles in a fast-moving terrestrial stream, were clearly visible in layers of exposed bedrock very near to the landing site.

Click HERE to view five things Curiosity has discovered

William Dietrich of the University of California, Berkeley, one of the science co-investigators on the project, said at the time that the streams could have existed for thousands and possibly millions of years between 3.5 billion and 4 billion years ago, a period when life on Earth was just beginning to emerge.

“Plenty of [scientific] papers have been written about channels on Mars with many different hypotheses about the flows in them. This is the first time we’re actually seeing water-transported gravel on Mars,” Dr Dietrich said.

Armed with 10 scientific instruments and 17 cameras, Curiosity is a sophisticated mobile laboratory controlled by computers that can be re-programmed from Earth. All its movements are planned in advance by a science team at mission control in Pasadena, some of whom even live by Martian sunrise and sunset rather than the 24-hour terrestrial clock.

The rover has over the past four weeks travelled 764 yards (699 metres) since it began to move away from a group of “science targets” where it had worked for the previous six months to hone its analytical skills.

It has now begun the arduous 1.6km journey to its main target, the base of Mount Sharp, a Martian mountain with exposed geological layers that may contain the all-important chemical signatures of previous life-forms laid down in sedimentary rock formations.

“We now know that Mars offered favourable conditions for microbial life billions of years ago,” said Dr Grotzinger, a research scientist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

“It has been gratifying to succeed, but that has also whetted our appetites to learn more. We hope those enticing layers at Mount Sharp will preserve a broad diversity of other environmental conditions that could have affected habitability,” he said.

It could take anywhere between six months and a year for Curiosity to finally reach Mount Sharp, depending on the stops it makes on the way to investigate any features of interest. But there is hope that this highly sophisticated box of scientific tricks may be able to answer the biggest question of all: was there ever life on Mars?

Curiosity: A mission on Mars

Curiosity landed on Mars using a unique “sky crane” that hovered overhead using a set of eight retro-rockets while lowering the rover down to the surface on nylon tethers. As soft landings go, this one was picture perfect.

The landing of the rover was probably the most technically difficult and breathtakingly ambitious part of the entire $2.5bn (£1.67bn) project.

It took seven minutes from the point at which the space probe carrying the rover entered the Martian atmosphere to the moment that the rover’s six wheels touched down on the surface of the Red Planet.

During that time the craft had to be slowed down from its entry speed of 13,200mph. This was achieved using a number of deceleration techniques, from S-shaped manoeuvres to take advantage of the friction generated by the probe’s heat-shield, to parachutes and retro-rockets.

In the end, it worked perfectly and the plutonium-powered Curiosity rover was lowered down to the surface in the most gentle of soft landings.

One Nasa scientist said that the entire landing was like trying to control and dissipate the energy of 25 high-speed trains at full throttle.

Steve Connor

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies