The mystery of shellshock solved: Scientists identify the unique brain injury caused by war

It is a century since cases were first reported in World War One

When the war poet Wilfred Owen wrote of “men whose minds the Dead have ravished” he was attempting to describe the mysterious effects of shellshock which started appearing during the First World War and of which he himself was a sufferer.

Now, a century after the first cases began to appear, scientists believe they have for the first time identified the signature brain injury that could explain why some soldiers go on to have their lives blighted by the condition.

After conducting autopsies on US combat veterans who survived improvised explosive device (IED) blasts in Iraq and Afghanistan but later died of other causes, researchers in the US found the ex-soldiers had a unique type of brain injury.

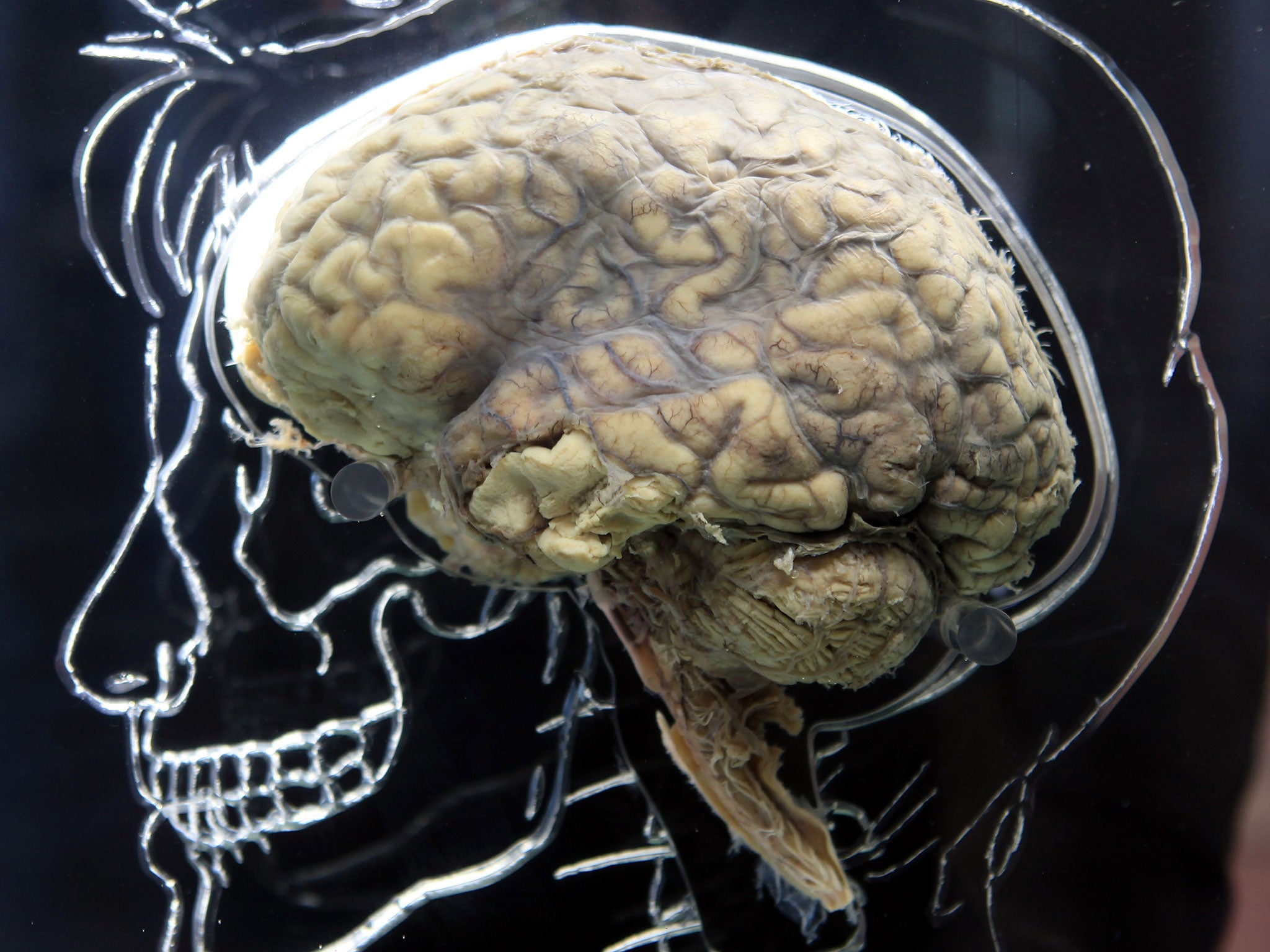

Described as a ‘distinctive honeycomb pattern of broken and swollen nerve fibres’, the injuries were not the same as those found in car crash and drug overdose victims, or sufferers of punch-drunk syndrome, which is caused by repeated blows to the head.

The lesions occurred in critical regions of the IED survivors’ brains, including in the frontal lobes, which control decision making and reasoning, lead the scientists to conclude that hidden brain injuries may play a role in the social and psychological problems faced by some combat veterans.

Vassilis Koliatsos, professor of pathology, neurology, and psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, one of the lead authors of the study, said: “This is the first time the tools of modern pathology have been used to look at a 100-year-old problem: the lingering effects of blasts on the brain.

“The location and extent of these lesions may help explain why some veterans who survive IED attacks have problems putting their lives back together.”

The heavy artillery bombardments of WWI meant that shellshock rapidly became one of defining features of the 1914-18 conflict. As early as December 1914 up to ten per cent of British officers and four per cent of other ranks were suffering from what was then termed “nervous and mental shock.”

In his poem 'Mental Cases', Wilfred Owen, who was diagnosed with shellshock in 1917, wrote sympathetically of the sufferers in his poem Mental Cases, but the condition, now more often referred to as post-traumatic stress disorder, (PTSD), was poorly understood.

With many senior officers taking the view that a long-lasting episode of shellshock was evidence of lack of character, some sufferers were executed for cowardice.

The conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan are believed to have led to a sharp increase in the numbers of soldiers suffering from PTSD, and the charity Combat Stress has estimated that about 50,000 British Iraq and Afghanistan veterans will suffer some sort of mental health problem in the coming decades.

Wounded: The Legacy of War

Show all 15The American researchers suggested that with insurgents making extensive use of IEDs in both conflicts, at least some of these mental health issues will be the result of the unique brain injury caused by surviving a blast injury.

Professor Koliatsos said: “Doctors treating IED survivors often see depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, and substance abuse or adjustment disorders. Life is very difficult for some of these veterans.

“It is important to understand that at least a portion of these difficulties may have a neurological foundation.”

The researchers examined the brains of five male IED survivors whose remains had been donated to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, and compared them to the brains of 24 people who had died of a variety of causes including car crashes, overdoses and heart attacks.

The distinctive honeycomb lesions were found in four of the five IED survivors, but not in people who had suffered other types of brain injury.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies