Inadequate minimum wage isn't working, says its chief architect Sir George Bain

Professor Sir George Bain says the value of minimum wage has fallen because it hasn't kept pace with inflation

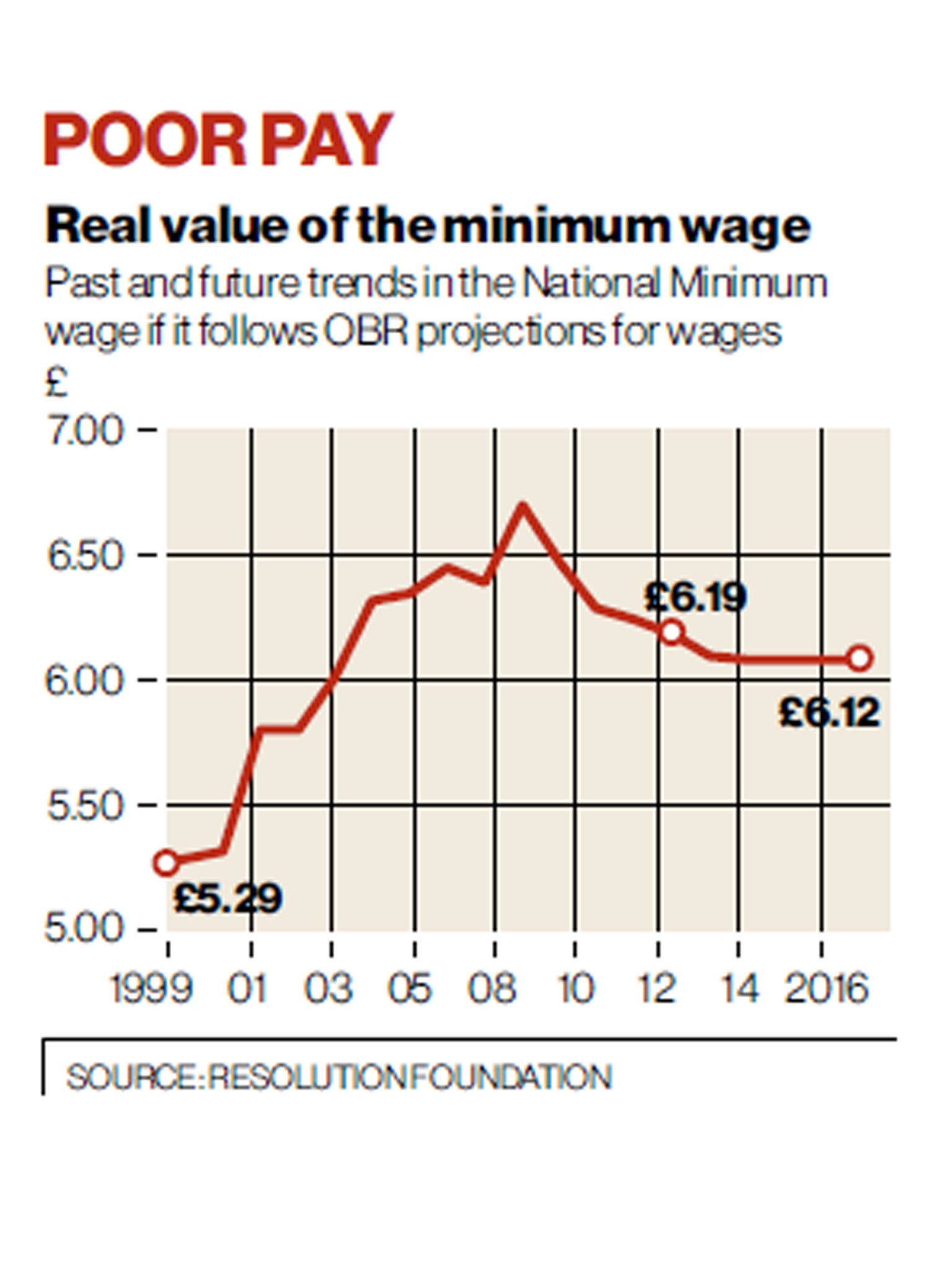

The national minimum wage is no longer working because its value has fallen, one of its key architects said as a new study showed it could be worth less in 2017 than it was in 2004.

The landmark measure, introduced by the Blair government 15 years ago this week, has dropped in value in real terms in the past five years after being pegged to wages, which have not kept pace with inflation.

Professor Sir George Bain, the first chairman of the Low Pay Commission which recommends the level of the minimum wage each year, told The Independent a “fresh approach” is needed because it is not addressing today’s problems. He believes the priority is to help the 3.6 million people who are above the legal minimum but below the “living wage” needed for a basic standard of living. That is paid voluntarily by about 250 employers and is worth £7.45 an hour, or £8.55 an hour in London.

The minimum wage is currently set at £6.19 an hour and covers 1.1 million workers. It has usually risen in line with median pay, which has fallen behind inflation in recent years.

The study by the Resolution Foundation, a think tank campaigning for better living standards for the 15 million people on low and middle incomes, predicts the legal floor would rise to £7.12 an hour in 2017 – the equivalent of £6.12 an hour in today’s prices and less than the £6.33 an hour it was worth in 2004. The prediction is based on Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts for wage growth. The foundation says that would mean “13 lost years” in the fight against low pay.

Professor Bain said that from its launch in 1998 to 2007, the minimum wage abolished the worst excesses of low pay but struggled to help the group earning less than the living wage. The foundation’s study says the proportion of workers earning below about £7.50 an hour dropped only slightly, from 22 per cent to 21 per cent, over this period. At that rate, it would take the UK 70 years to reach the average rate of low pay in the 34 nations in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Professor Bain said: “In the early years of the minimum wage, we were successful in tackling some of the worst excesses of low pay and exploitation. This was our number one priority. The challenge for the next 15 years is much harder - how to help people earning above the minimum wage but below the living wage. Yet on current forecasts it looks like the gap between the minimum wage and the living wage could only widen in the coming years. Fresh thinking is going to be needed.”

The academic added: “Of course, this doesn’t just mean saying the minimum wage should rise regardless of the economic context, nor that you can impose a statutory living wage in such a varied labour market. But in other areas of economic policy, from inflation to public debt, the government is much clearer about the UK’s long-term goals - and we have bodies like the OBR to guide us. With low pay carrying such high social and economic costs – remember that the minimum wage brings savings for the public purse - we should be asking if it deserves a similar, more long-term and more systematic approach.”

The foundation estimates that if everyone were paid the living wage, the Government would save £2.2 billion a year through higher tax and national insurance receipts and lower spending on tax credits and benefits.

Professor Bain is chairing a review of the minimum wage for the foundation. It is considering whether the Government should make tackling low pay a clear long-term goal of economic policy, with the Low Pay Commission advising on how it would be achieved. One option is for the commission to give more “forward guidance” on how the legal floor might be raised to give business more time to adapt.

Ed Miliband, the Labour leader, is a supporter of the living wage and it has been introduced by some Labour councils. It is in line with his vision of “responsible capitalism” and boosting incomes rather than relying on expensive handouts like tax credits the state can no longer afford.

Although 2015 is likely to see a “living standards election,” the Labour manifesto is unlikely to pledge to impose a living wage on firms by legislation, as that could cost jobs in some sectors. Labour could encourage its growth by restricting government contracts to firms paying it.

Since 2001, the campaign for a living wage has helped more than 45,000 employees and put more than £210 million into the pockets of the low paid. Boris Johnson, the Conservative Mayor of London, is another backer. He has said: “By building motivated, dedicated workforces, the living wage helps businesses to boost the bottom line and ensures that hard-working people who contribute to London's success can enjoy a decent standard of living."

Case study: ‘I work really hard but cannot afford the basic things’

Albeiro Ortiz is a 46-year-old cleaner originally from Colombia who works in London. Mr Ortiz is a member of the IWGB union.

I have worked as a cleaner at the Barbican Centre for the company MITIE for 40 hours a week – 6am to 2pm – since I first came to England two-and-a-half years ago.

In that time, there has been a big increase in the cost of living: rent, transport and everything is increasing but the minimum wage always remains low regardless. It feels really unjust – some people I work with have been earning the minimum wage for over eight years.

I used to buy two weeks-worth of food for around £40 and now that same £40 covers a week’s shop. We cannot buy the things we need, the things which are necessary.

I do an essential job and work really hard and should at least be able to afford the basic things in life with the salary I earn but it is just not possible. I have had to cut back on certain things. I always keep an eye out for food offers and can only afford to travel by bus, which I spend several hours a day on.

I wake up at 4am and get home from work at around 4pm, working an eight-hour shift. I then go to English classes which start at 6pm and I get home at 9.30pm and then I just have enough time to see my baby and get enough sleep for the next day.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies