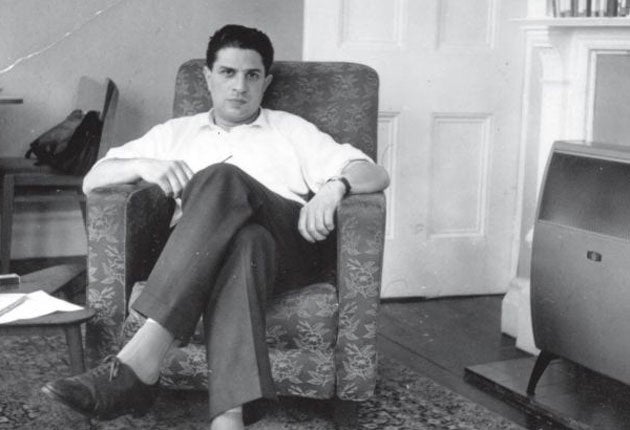

Ralph Miliband: The father of a new generation

His two sons are currently battling it out for the Labour leadership. But who was Ralph Miliband – and how would he have cast his vote? Andy McSmith investigates an inspirational political parent

If Ralph Miliband were still alive, which of his two sons would he be backing for the Labour leadership? The most probable answer is neither, since it is doubtful that he would even be eligible to vote. Indeed there was a leadership election about to get under way when he died, on 21 May 1994, and he was not eligible to vote in that – though, even if he had been, we can be sure that he would not have voted for Tony Blair. Had he lived for another two decades, it is still quite likely that he would have refused to join the party now dominated by his sons.

Ralph Miliband's contribution to modern political thought included a ferocious assault on just the kind of social democratic politics that his two boys are, in their different ways, now battling to keep alive. His book, Parliamentary Socialism: A Study of the Politics of Labour, published in 1961, was absorbed by the student generation radicalised by the Vietnam war and disillusioned by the Labour government that came to office in 1964. One of the reasons that the heir to one of the most famous names in Labour Party history, the journalist Paul Foot, did not follow his father and uncles into the party was that he had read Miliband when he was young. Another person who devoured Miliband's work, and was a lifelong friend, was Tariq Ali, the best known of the 1960s student radicals, whose politics are so far to the left that, when he applied to join the Labour Party during Michael Foot's time as leader, the National Executive refused to let him in.

The brothers now vying for the party's leadership were asked during a televised debate last weekend whether they considered themselves to be socialists. Each said yes, and gave an outline definition of what he meant by socialism. But it is a matter of plain fact that neither David nor Ed Miliband can be called a socialist under any definition of the word that their father would have used. The brothers have both accepted the existence of the capitalist system as an established fact, and interpret socialism as a mission to combat its injustices and protect its potential victims. For all their much-hyped differences, David and Ed are closer politically to one another than either is to their father – or indeed to their mother, Marion, who has kept out of the public eye, but is still very much alive. (In August, Ed let slip that she is expected to give her first preference vote to the outsider, Diane Abbott, the most left-wing candidate in the field.)

There was only one interlude when Ralph Miliband thought that the Labour Party might be the instrument by which socialism could be achieved in Great Britain. That was 30 years ago, when Tony Benn was at the peak of his influence, and the Labour Party drew up an election manifesto promising an unprecedented level of state intervention in the economy, on which the party fought and heavily lost the 1983 general election. For Ralph Miliband, the issue was never how to reform the capitalist system, but how to get rid of it. His definition of a socialist was someone who advocated the common ownership of the means of production, an idea finally expunged from Labour's constitution 15 years ago by Tony Blair – and one which neither of his sons is proposing to reinstate.

Ironically, however, it is the brothers, who were raised in the relatively comfortable milieu of London's middle-class, intellectual left, who have the firmer grasp of what the British public will support and vote for. The father, who came up the hard way, was the dreamer.

Ralph Miliband was only one generation removed from the ghetto. His parents both came from Warsaw's Jewish quarter and emigrated in the early 1920s to Brussels, where they first met. Ralph was born there on 7 January 1924. His father, Sam, was a skilled craftsman who designed and made high-quality leather goods, which brought the family a secure living until the depression of the 1930s, when Ralph's mother, Renia, was forced to supplement their income by travelling about selling ladies' hats, a role she found humiliating and tried to conceal from the neighbours. Though Renia spoke fluent Polish, Sam had only an elementary education and probably did not speak a word of any language other than Yiddish until he began painfully teaching himself French – and was able to learn about the outside world from French newspapers.

When Germany invaded Belgium in May 1940, the family of four packed and went to Brussels meaning to catch a train to Paris, but were too late. When they returned, disconsolate, to their Brussels apartment, their 16-year-old son stubbornly announced that he was going to walk to France. His 12-year-old sister, Anne-Marie, was too young for the journey, so father and son set out, leaving mother and daughter behind. Once they were under way Sam Miliband changed course, against his son's protests, and they walked more than 60 miles from Brussels to Ostend, where they caught the last boat to Britain, arriving destitute, on 19 May 1940.

The first thing the teenager had to do was change his first name. His parents had called him Adolphe, not a good name to be using in London during the Blitz, so he began to call himself Ralph. The only work they could obtain was the depressing task of removing furniture from bombed out homes in the Chiswick area. It was six weeks before they even found a way to get a message back to Renia that they were in London not Paris, and 10 years before the family was reunited. Fortunately, while travelling south to sell hats, Renia had struck up a friendship with a French family who had a farm near Mons. After being interrogated by the Gestapo, and having read an order that all Jews in Brussels were to report to a clearing station, she and her daughter absconded in secret to the farm, where they found shelter, with other refugees, for the rest of the war. But more than 40 members of the extended Miliband family and many of Ralph's boyhood friends were less lucky or less enterprising, and died at the hands of the Nazis.

In January 1941, with help from the International Commission for Refugees, Ralph – as he was now called – enrolled at Acton Technical College. His English was improving in great strides: he passed his first-year exams, then applied to the Belgian government-in-exile for help in getting in to the London School of Economics – which was granted, despite the technicality that neither he nor his parents had ever been Belgian citizens. By now, Ralph had acquired what was to be a lifelong interest in left-wing politics. He would later claim that one of the first sites he visited in London was Karl Marx's grave, in Highgate, where he stood with a clenched fist and swore a private oath to be faithful to the workers' cause. By the time he reached Cambridge, where the LSE was evacuated for the duration of the war, the Soviet Union had been drawn in to the conflict on Britain's side, and most of the students had communist sympathies.

The dominant figure within the LSE was Harold Laski, a member of the Labour Party's National Executive whose enemies accused him of being a closet communist. It was to Laski that Clement Attlee addressed his celebrated rebuke that "a period of silence on your part would be welcome". But the young Miliband looked to Laski as an intellectual mentor who "taught a faith that ideas mattered, that knowledge was important and its pursuit exciting". Miliband too was close to the Communist Party but never joined. He would claim to have been an independent Marxist all his adult life. His first published essay, written in French in a magazine for Belgian exiles, called rather mildly for reform of the House of Lords.

As a teenager, Miliband was liable for military service, and for some reason wanted to join the Navy, which he did, with Laski's help. He took part in the D-Day landings, in the liberation of Crete, and was aboard the first Allied ship to sail into Athens in October 1944. His fellow sailors seem to have looked upon him as a rare beast. "I think there is an anti-Semitic trend, however weak, in every non-Jew," he glumly confided in his diary. He was generally the only Jew, and certainly the only stateless, Belgian-born, French-speaking LSE student among the enlisted men, and the only one trying to set aside time to read Marx's Das Kapital. He was shocked to hear sailors joke about sex, and even more so to discover, towards the end of the war, that there was homosexuality aboard ship.

Demobilised in 1946, he went back to the LSE and applied successfully for British citizenship. There was a crisis in the family when his father was threatened with deportation back to Poland, the only country of which he had a valid claim to be a citizen, but once that had been sorted, the family was reunited. In 1961, Ralph married one of his former students, Marion Kozak, who had survived a war-time experience even more hazardous than Ralph mother's. Her family were prosperous Czech Jews who were forced into the ghetto when their country was occupied. Her father and grandparents were rounded up and killed, while Marion, her sister and her mother hid out in the homes of courageous friends, keeping one step ahead of discovery and death. She reached Britain in 1947.

Intellectually, Ralph Miliband came into his own in the 1960s. The revelation of Stalin's crimes and the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956 were traumatic events for British intellectuals who had signed up to the communist cause, though not to Miliband, who had never joined the party, but was now part of the movement known as the New Left that tried to recreate revolutionary Marxism free from the dead hand of Soviet communism. Having completely mastered English, he wrote in a straightforward style that made him a more accessible thinker than the average left-wing intellectual. Students who met him were also impressed by his unpretentious manner and his love of teaching.

Hilary Wainwright, editor of the magazine Red Pepper, was a member of that Sixties generation who knew Miliband well. "I think because he had such a difficult life, he was very egalitarian," she said. "People on the left can be very snotty; you get people who are interested in the masses, but not in the individual; but he was just instinctively non-elitist. Out of respect, he was incredibly punctual in turning up to meetings. We lazy buggers would turn up late and Ralph would be in the room talking to everybody and taking everybody seriously."

In those heady days, there were intelligent people who believed that the struggle between capitalism and socialism would end with capitalism collapsing under its unsustainability. When, in 1977, Ralph Miliband published one of his other seminal books, Marxism and Politics, that still appeared to be a plausible outcome, particularly given the seriousness of the economic crisis in the UK. But as the 1970s morphed into the 1980s, with the rise of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher in the West, and later of Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin in the East, that faith in an inevitable socialist victory became harder to sustain.

When Ralph Miliband first took an interest in politics, 70 years ago, Marxism was the new kid on the block: it was dynamic, it was the future, while capitalism was seemingly old and decaying. By the time he was 70, the capitalist system was going through a dynamic self-renewal while communism in Eastern Europe had collapsed under the weight of its sclerotic inability to reform. In an essay on Miliband's politics published earlier this month, the academic John Gray described him as "a theorist of revolution who failed to notice the radical transformations going on around him".

But the old man never lost faith. He did not like the old left-wing slogan "pessimism of the intelligence, optimism of the will" which he felt implied that true socialists must keep on struggling although their enterprise is doomed to fail. Not so, he wrote, when the communist system in the Soviet Union was starting to come apart. There was no good reason, he maintained, to believe that "the project of creating a co-operative, democratic egalitarian society" was an illusion, either in the 1960s or the 1980s.

There is a nobility and a drama in the life of Ralph Miliband that is lacking in the steady, pragmatic political careers of his sons. But the brothers are arguing about what can be done now. By contrast, waiting for Ralph Miliband's vision of the future to come to pass could be like waiting for Godot.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies