Cells from patients' own blood spur cancer remissions

Nine leukemia patients are cancer-free after being treated with genetically-altered versions of their own immune cells, giving strength to a promising new approach for treating the blood cancer.

The trial of 12 patients, two of them children, bolsters findings from 2011. Then, scientists from the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia reported that two of the first three patients treated showed no traces of the malignancy after getting the therapy. Today's results were presented at the American Society of Hematology's annual meeting in Atlanta.

For Walter Keller, 59, who had failed every other treatment for his chronic lymphocytic leukemia diagnosed in 1996, the regimen meant he's been in remission since his treatment in April. Before the therapy, "I thought I had a year to live," he said.

"I feel better than I have in a long, long time," said Keller, of Upland, Calif., in a telephone interview. "I'm excited because I think this will help a lot of people."

The approach developed by University of Pennsylvania scientists has since been acquired by Novartis.

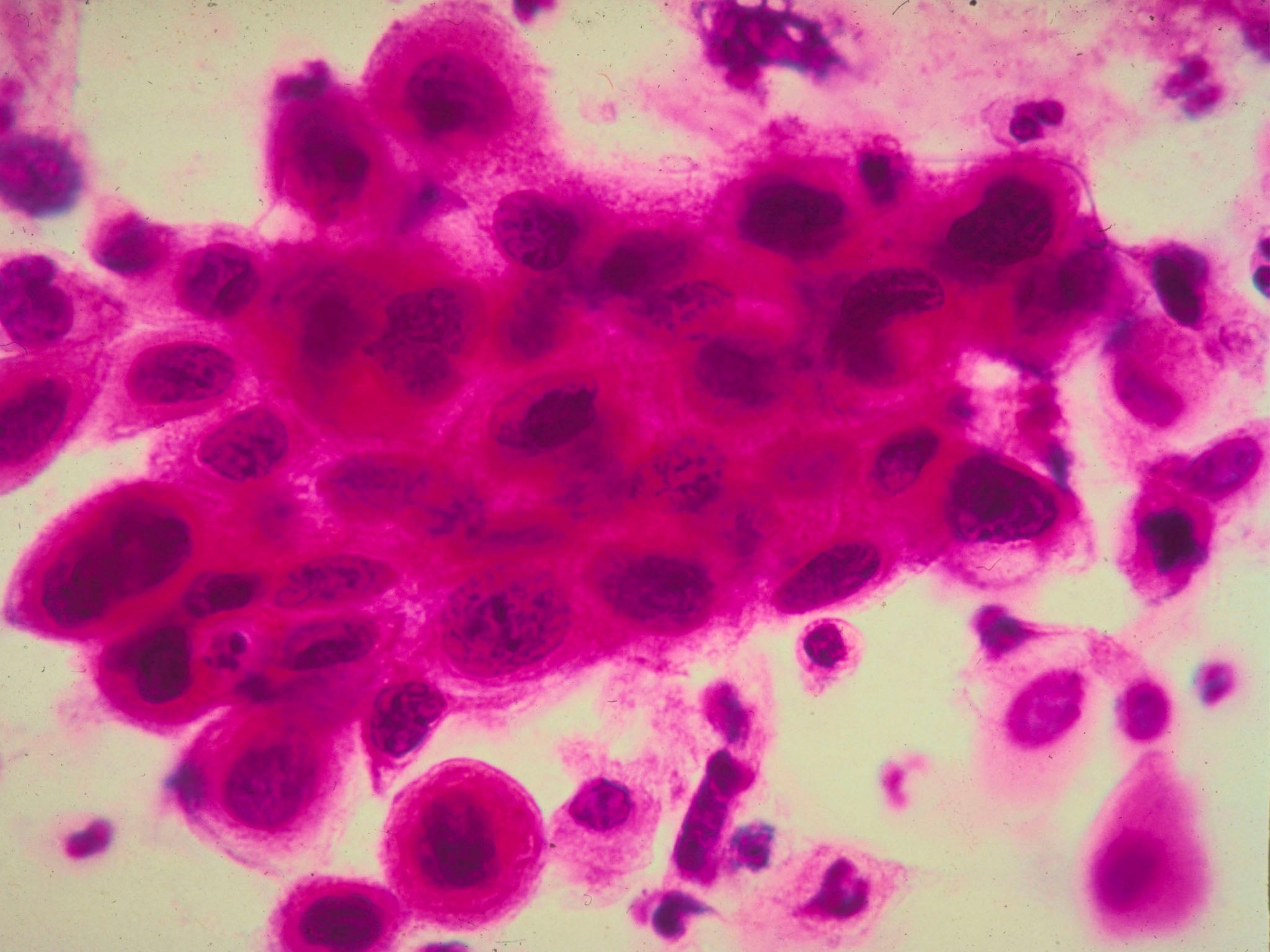

The scientists, led by Carl June, a professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania and a study author, used genetic engineering to manipulate white blood cells extracted from the patients. The researchers reprogrammed the cells to specifically target the leukemia cells and reinjected them into the patients.

CLL is a slow-growing cancer that starts from white blood cells in the bone marrow and interferes with the production of healthy blood cells. The condition leads to complications such as immune deficiencies and swollen lymph nodes. The disease strikes about 16,000 adults each year and 4,600 die from it, according to the American Cancer Society.

The disease is treated with chemotherapy. Another approach is bone marrow transplant in which chemotherapy is first given to kill diseased cells then replaced with healthy ones from bone marrow extracted from the patient or a donor.

Keller underwent chemotherapy and then a stem cell transplant in 1998 and 1999. He was in remission for 5 and a half years. He then underwent a different chemotherapy regimen and got a second stem cell transplant. The cancer came back again in 2010, and he had no options left. He was one of 10 adult patients treated so far.

"No patient who had complete remission has lost it," said Keller's doctor, David Porter, director of blood and marrow transplantation at the University of Pennsylvania's Abramson Cancer Center. "It's unusual to have a treatment that can work to this magnitude and until now, this duration."

Two of the original three patients treated have maintained their remissions over 2 years later. The scientists found signs of the designer blood cells still circulating in their bodies.

Two girls, ages 7 and 10, were also treated for a fast- growing blood cancer that affects children called acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Both had been treated and had then relapsed, said Stephan Grupp, director of Translational Research in the Center for Childhood Cancer Research at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. He presented research on their care at the hematology meeting.

One of the girls has been in complete remission in the 8 months since her treatment. The other had a remission of "a few months" before relapsing again, Grupp said. The younger girl had severe side-effects.

Previous studies have documented severe, flu-like illness in patients treated with their pumped-up immune cells. The 7- year-old's severe reaction helped explain what was happening, Grupp said. Her levels of an inflammatory protein called IL-6 were very high, 998 times her ordinary level. His group treated her with Roche's Actemra, approved for rheumatoid arthritis, which targets the protein. Because her levels of another inflammatory protein called TNF were high, she was also treated with Amgen and Pfizer's Enbrel.

"The next morning, she was dramatically better," Grupp said.

Her reaction suggests that the illness caused by the treatment is the result of an overactive immune system. Previously it wasn't clear what had caused the reactions, since tumors also release poisons when they're broken up to be cleared from the system.

Three adults being dosed with their own altered immune cells were also treated with Actemra, which lowered high fevers, restored abnormally low blood pressure, and allowed patients to easily breathe again.

"Everyone says I look good," said Keller, who also experienced flu symptoms after the treatment. "I guess I looked like crap before."

Novartis funded a $20 million research center at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, as well as paying an undisclosed amount of money for rights to the therapy in August. The therapy will be called CTL019 by the drugmaker.

Today's research was funded by the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, the Alliance for Cancer Gene Therapy and the National Institutes of Health.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies