Elliot Rodger killings: My son the mass killer

America’s lastest shooting spree leaves many more bereaved, none more so than the gunman’s parents. As others’ experiences show, Peter and Chin Rodger face hatred and a life wracked with guilt for their son’s actions

In 2009, 10 years after her son Dylan and his classmate Eric Harris shot dead 12 fellow students, a teacher and finally, themselves at Columbine High School in Colorado, Susan Klebold revisited that day in a powerful personal essay for O magazine. “While I perceived myself to be a victim of the tragedy, I didn’t have the comfort of being perceived that way by most of the community,” Ms Klebold wrote. “I was widely viewed as a perpetrator or at least an accomplice since I was the person who had raised a ‘monster’.”

A week ago, one more mass murderer entered the public consciousness, as 22-year-old Elliot Rodger killed six people and himself in the small college town of Isla Vista, California. The succession of shootings at US schools and college campuses in the years since Columbine may have softened attitudes towards families like the Klebolds. But while the palpable grief of a victim’s parent is pure, the grief of a dead killer’s parent is mixed with shame and guilt – for what they and others may perceive as their partial responsibility for their child’s crimes.

Many choose to retreat from public view entirely. The family of Jared Lee Loughner – who killed six and severely injured several others, including congresswoman Gaby Giffords, in a shooting in Tucson, Arizona in 2011 – boarded up windows and built high fences around their home. By contrast, Rodger’s parents, Peter and Chin, have already released a heartfelt statement, which their friend Simon Astaire read on ABC’s Good Morning America on Thursday.

“We are crying in pain for the victims and their families,” the statement said. “It breaks our heart on a level that we didn’t think possible. The feeling of knowing that it was our son’s actions that caused the tragedy can only be described as hell on earth.” Rodger’s parents had “literally diminished in size”, Mr Astaire added. “They are crippled in pain. Every part of it is talking about [the other victims], not their son.”

As the details of Rodger’s short life have emerged, it has become increasingly clear that there was little more his mother and father could have done to prevent such an unpredictable tragedy. The British-born student had been in therapy since he was nine years old, and his divorced parents had long been concerned that he might take his own life. After seeing some of the troubling videos that he posted on YouTube, Rodger’s mother had even asked police to check on her son. Sheriff’s deputies visited his apartment in April, where he told them it was all simply a misunderstanding. Mr Astaire said: “They don’t place any blame on the police, because Elliot fooled everyone. No one knew the man he was turning into.”

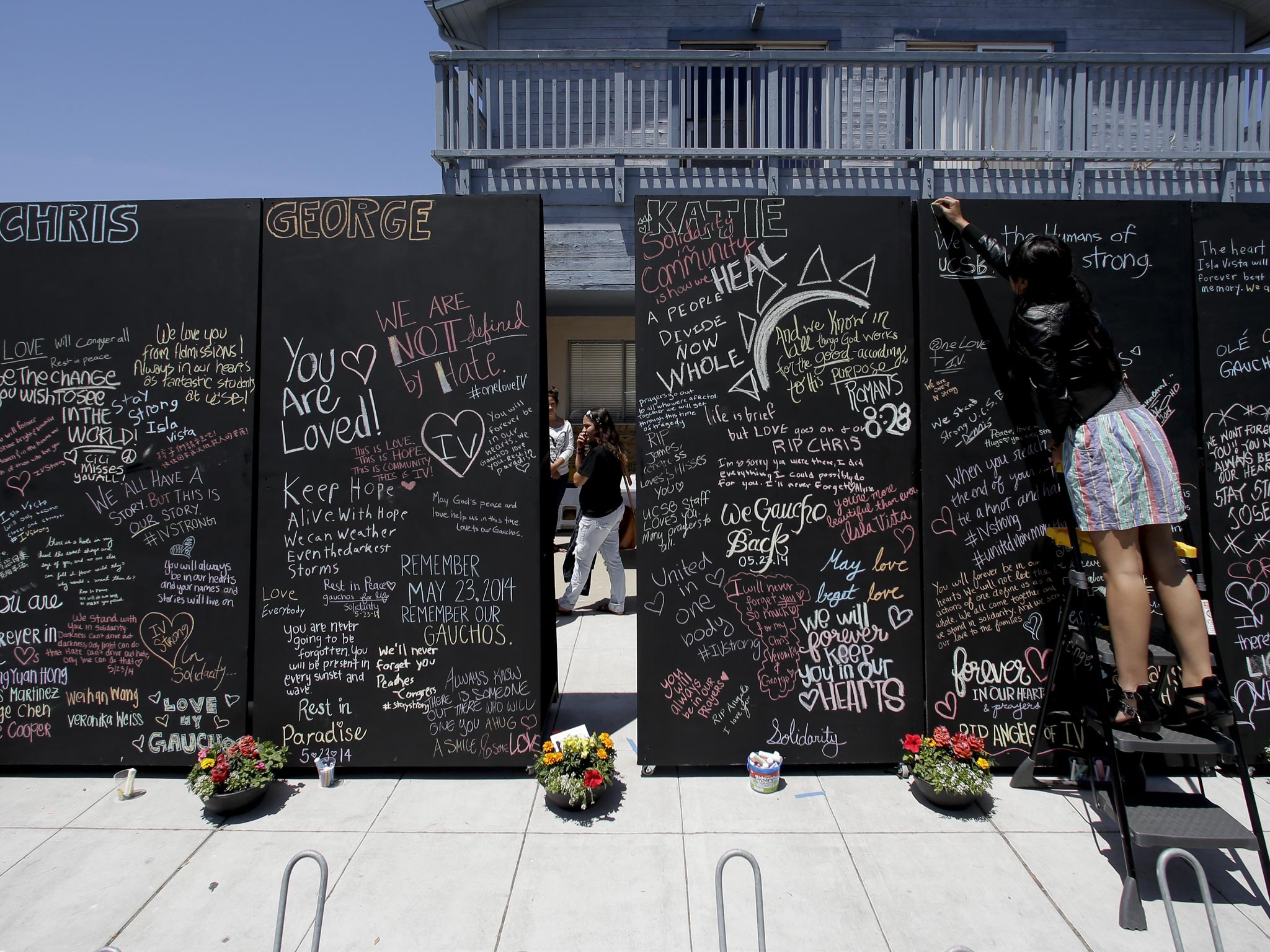

The aftermath of the Santa Barbara shooting

Show all 10It was only last Friday, when they received his 140-page “manifesto” outlining his plans for “retribution”, that the Rodgers realised their son might harm others, too. After glancing at the first paragraph of the email, Chin Rodger turned to Elliot’s YouTube page, where she found his now-notorious final video, promising “slaughter”. She and Peter raced towards Isla Vista from Los Angeles, only to hear the first reports of Elliot’s rampage on the car radio.

Rodger’s parents have reportedly not read their son’s full manifesto, but if they had they would have seen his threats to kill members of his own family. Despite his designer clothes and his BMW, he even blamed his “damnable mother” and “failure of a father” for his own perceived lack of wealth, which he felt had contributed to his social alienation.

Adam Lanza, who killed 20 children and six adult staff at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut in December 2012, appears to have shared with Rodger an irrational hatred of women. Though his writings were sparser and less lucid than Rodger’s, a document found on Lanza’s computer seeks to explain why women are inherently “selfish”. The 20-year-old began his rampage by killing his mother Nancy at their home, yet public opinion quickly implicated her in his crimes, not least because she was a gun enthusiast who owned firearms and had taught her son to shoot.

Lanza’s father Peter was divorced from Nancy, and Adam had cut off contact with him two years before his death. In his only interview since the Sandy Hook massacre, with Andrew Solomon for The New Yorker, Mr Lanza said he still doesn’t believe that anyone could have foreseen the killings. Like the Rodgers, the Lanzas did all they could to help their son, who was severely withdrawn and had been diagnosed with autism. He too had undergone therapy, and mental health professionals had spotted no warning of what was to come.

Unable to deny her son’s increasingly obscure and obsessive demands, Peter Lanza said his ex-wife was close to “becoming a prisoner in her own house” prior to her death. After the killings, Mr Lanza remained in his role as an accountant for a subsidiary of General Electric. He considered changing his name, he said. “But I feel like that would be distancing myself and I cannot distance myself. I don’t let it define me, but I felt like changing the name is sort of pretending it didn’t happen and that’s not right.”

In her essay for O, “I Will Never Know Why”, Susan Klebold said that for months after her son’s infamous murders and suicide, she refused to use her last name in public. She also cited one newspaper survey that suggested 83 per cent of respondents thought “the parents’ failure to teach Dylan and Eric proper values played a major part in the Columbine killings”. The Klebolds and Harrises faced lawsuits from the victims’ families and eventually paid large settlements.

Yet the Klebolds had no notion of what their son was planning: Dylan seemed a relatively normal teenager, shy but capable of making friends. His notebooks and school essays expressed an inner darkness, but only took on deeper significance when police pieced them together after the killings. “I tried to identify a pivotal event in his upbringing that could account for his anger,” Ms Klebold wrote. “Had I been too strict? Not strict enough? Had I pushed too hard, or not hard enough? In the days before he died, I had hugged him and told him how much I loved him.”

After interviewing the Klebolds for his book Far From the Tree, about the families of extreme children, Solomon said he was mystified by Dylan Klebold’s actions. “Sue Klebold’s kindness (before Dylan’s death, she worked with people with disabilities) would be the answered prayer of many a neglected or abused child, and [her husband] Tom’s bullish enthusiasm would lift anyone’s tired spirits.” Solomon also wrote: “Unfortunately, virtuous parenting is no warranty against corrupt children. Yet these parents find themselves morally diminished, and the force of blame impedes their ability to help – sometimes even to love – their felonious progeny.”

In the opinion of Lionel Dahmer, father of the serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, it is a parent’s love that can blind them to a child’s capacity for evil. In his own book about his son’s crimes, A Father’s Story, Mr Dahmer wrote, “In the eyes of parents I think children always seem just a blink away from redemption. No matter to what depths we watch them sink, we believe they need only grasp the lifeline and we can pull them safely to shore.”

Following Dahmer’s conviction, his mother Joyce Flint embraced her work with Aids victims at the height of the Aids crisis. Elliot Rodger’s parents have suggested that they, too, will try to mine their tragedy for good. “It is now our responsibility to do everything we can to help avoid this happening to any other family,” their statement said. “Not only to avoid more innocence destroyed, but also to identify and deal with the mental issues that drove our son to do what he did.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies