The Big Question: Why are so many countries opposed to Kosovo gaining its independence?

Why are we asking this now?

Because Kosovo this week declared itself to be Europe's newest country. Some 17 years after the dissolution of Yugoslavia – and after a ghastly cavalcade of ethnic cleansing, gruesome atrocities, forced expulsions and a civil war that killed 10,000 before Nato intervened – the people of Kosovo have declared themselves independent.

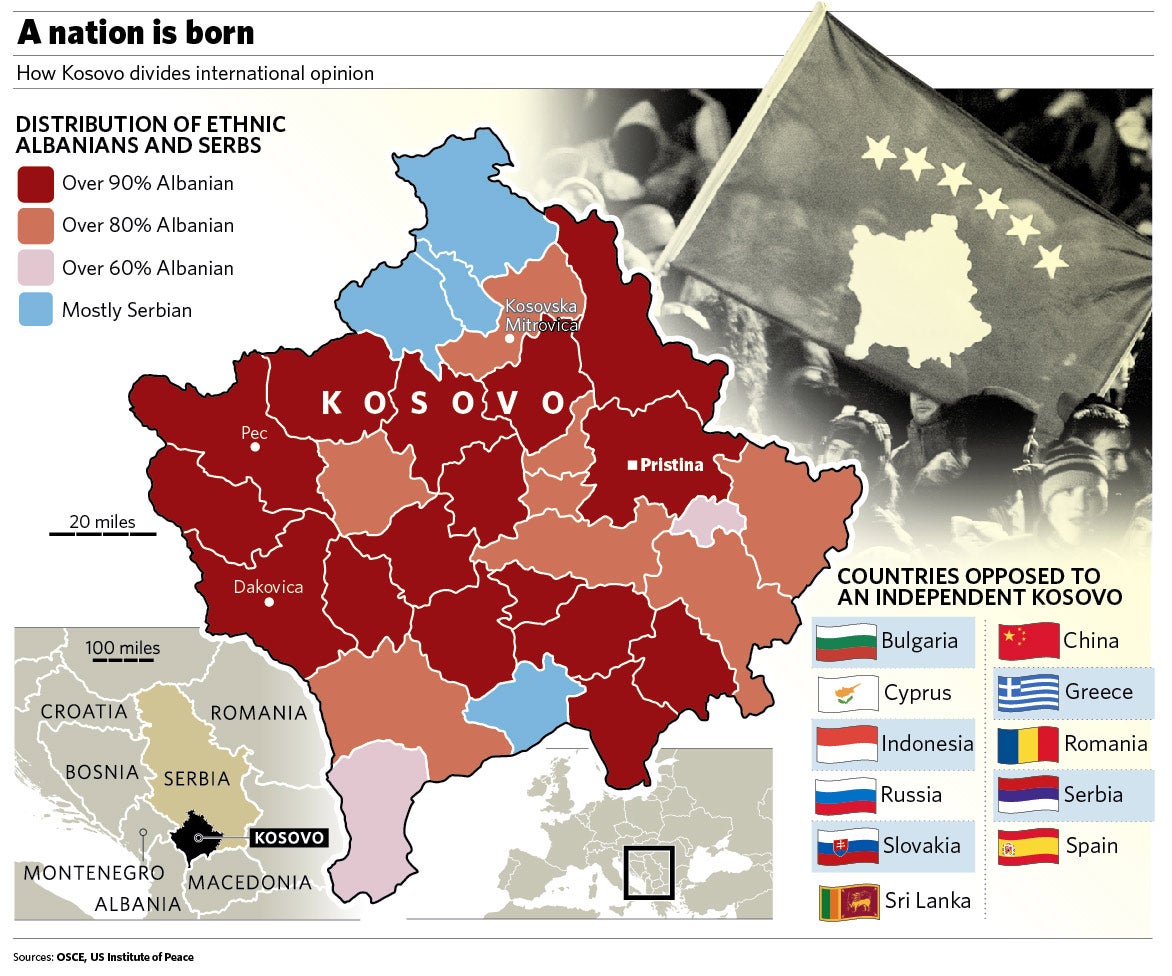

Since 1999 they have lived under a United Nations protectorate while conducting negotiations with the neighbouring Serbs to find a mutually acceptable constitutional status for the region. When the talks broke down, the provisional government unilaterally declared independence as the Republic of Kosovo. Some 90 per cent of the two million people are ethnic Albanians, just 10 per cent Serbs. Now the creators of the world's 193rd independent country have sent 192 letters to governments around the world seeking formal recognition of their independence.

What do the Serbs think?

They are very unhappy. They regard Kosovo as the heart of its state since medieval times, even though 90 per cent of its population is of a different ethnicity. The Serbian prime minister, Vojislav Kostunica, described Kosovo as a "fake country".

So who's on what side?

The countries who participated in the Nato strikes against Serbia to end the atrocities, led by the United States. President George Bush has already officially recognised Kosovo as an independent state. So will most of the big European nations – Britain, France, Germany and Italy – and the Japanese government is "moving toward recognising" Kosovo, pronouncing developments in line with Japan's criteria for recognising states.

Other EU members – Spain, Greece, Cyprus, Bulgaria, Romania and Slovakia, have said they will not. Other countries opposed to an independent Kosovo include Sri Lanka and Indonesia. The neighbouring Balkan states are also divided. Croatia and Macedonia are pro Kosovo, but Bosnia and Herzegovina is not. Other states, like Malta and Portugal, want Kosovo's future be decided at the UN Security Council.

Why is the international community so divided?

In part it reflects each government's differing sense of whether the ethnic Albanians, now Kosovans, were primarily the victims of the Serbs in the war a decade ago. "Serbia effectively lost Kosovo through its own actions in the 1990s," said the Irish foreign minister, Dermot Ahern. "The bitter legacy of the killings of thousands of civilians in Kosovo and the ethnic cleansing of many more has effectively ruled out any restoration of Serbian dominion in Kosovo."

In part it reflects convictions about the solutions to intractable foreign relations problems. In part it is a reflection of the domestic priorities of some governments who fear that support for Kosovo's unilateral declaration could fan separatism in their own countries.

What are the arguments?

The Americans, and most of Nato, believe that a definition resolution of the status of Kosovo is essential for the Balkans to become stable. "A negotiated solution was not possible," said the German foreign minister, Frank-Walter Steinmeier. "Peace and stability are the order of the day," said the British foreign secretary, David Miliband. Such is the population imbalance between ethnic Albanians and Serbs that autonomy was inevitable.

The other side counters with high-minded arguments about the inviolability of national sovereignty. "We will not recognise [Kosovo] because we consider," said the Spanish foreign minister, Miguel Angel Moratinos, "this does not respect international law".

But it is perhaps significant that those opposing recognition mostly have problems with their own separatist or secessionist movements. "Cyprus, for reasons of principle, cannot recognise and will not recognise a unilateral declaration of independence," the Cypriot Foreign Minister, Erato Kozakou-Marcoullis, said. "This is an issue of principle, of respect of international law, but also an issue of concern that it will create a precedent in international relations."

It had, she said, perhaps protesting too much, "nothing to do with the occupied Cyprus, it's not because we're afraid that the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) would declare independence because they already did it in 1983 and got a very strong reaction from the (UN) Security Council."

There was similar talk from Sri Lanka. "We note that the declaration of independence was made without the consent of the majority of the people of Serbia and is a violation of the Charter of the United Nations, which enshrines the sovereignty and territorial integrity of member states," a Sri Lankan government statement said, suggesting Kosovo could create an unmanageable precedent in "the conduct of international relations and the established global order of sovereign states".

Those on the other side dismiss this. Kosovo, said the British Foreign Secretary, was a "unique situation which deserves a unique response".

What about the Russians?

It too has its secessionists. Usman Ferzauli, the man who styles himself the Foreign Minister of Chechnya, has just, helpfully, backed Kosovo's declaration. But when he talks about "leading an armed struggle against the world's most aggressive and militarised power for the latest 14 years" he is not talking about the ethnic Albanians but their fellow Muslims in Chechnya, who enjoyed a brief period of autonomy before Moscow re-established control.

There are bonds of cultural and ethnic kinship between the Serbs and Russians. Europe is increasingly wary of the Slavic Bear. The Russians still have their carrier fleet anchored not that far away. Russia insists there is no basis for changing a 1999 security council resolution on Kosovo's status – and says that Belgrade must agree to any change.

What is likely to happen?

The US and the European members of the UN Security Council will back Kosovo's independence. But Russia and China will not. Russia will block Kosovo's membership of the United Nations. Serbia will use all diplomatic means at its disposal to block Kosovo's recognition – and will probably block Kosovo's access to the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe and the Council of Europe.

The real questions are less glamorous and more profound. Unemployment in Kosovo is over 40 per cent, corruption and organised crime is bad, and wealth per person is just 5 per cent of the EU average. The troubles are far from over yet.

Is independence for Kosovo a good thing?

Yes...

* 90 per cent of its people are non-Serbs and should be allowed to determine their own fate

* Serbia effectively lost Kosovo through its own actions in the atrocities and ethnic cleansing of the 1990s

* Kosovan independence is the logical working out of the collapse of Communist Yugoslavia after the Berlin Wall came down

No...

* Kosovo has formed the heart of the state of Serbia since medieval times

* All the people of Serbia should have been allowed to vote on the issue of Kosovan independence

* It sets a dangerous precedent for other parts of the world where rebels want to break away

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies