Hiroshima and the danger of nuclear weapons: A glimpse of what might befall us

During the Second World War, the United States Army Air Forces destroyed dozens of Japanese cities with firebombs, killing hundreds of thousands of civilians. The Japanese military behaved even more cruelly. It was responsible for the deaths of anywhere from 10 to 30 million civilians throughout Asia. As the historian John Dower has noted, the war in the Far East was truly a "war without mercy".

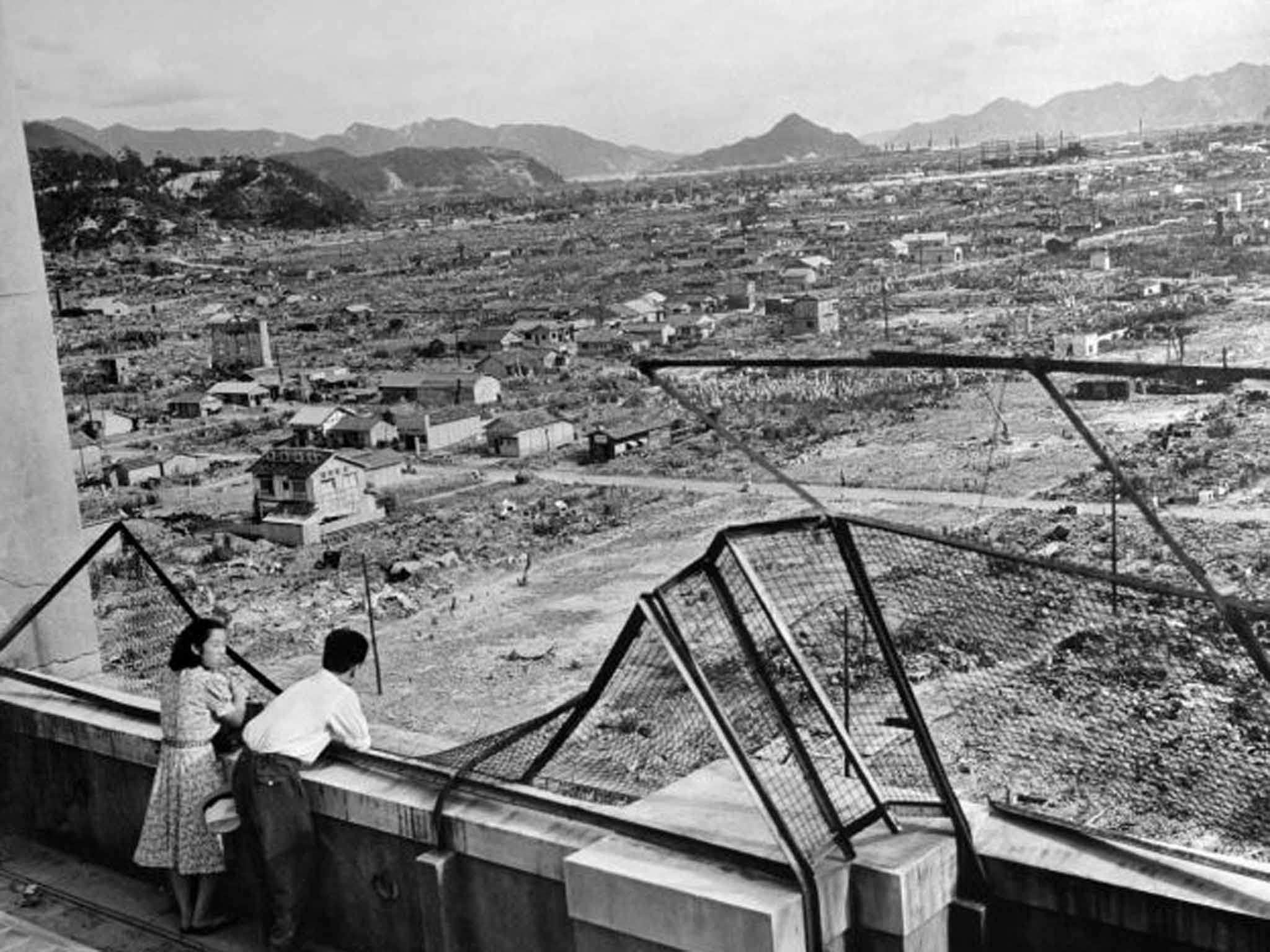

Amid all that carnage, the destruction of Hiroshima stands apart. On 6 August 1945, Hiroshima became the first city destroyed by a nuclear weapon and soon loomed as a harbinger of wars to come, a symbol of how science and technology could bring annihilation on an unprecedented scale.

The strategic importance of the atomic bomb was recognised immediately. Countless speeches and newspaper articles stressed how warfare had been transformed by a new weapon. But a magazine piece by a 31 year -old journalist – published in The New Yorker a year after Hiroshima and later released as a short book – shocked the world. John Hersey calmly described what a nuclear explosion does to a city and its inhabitants. What had been abstract and theoretical became horribly concrete. Few works of literature have had the impact of Hiroshima. The fact that no city has vanished in a mushroom cloud since its publication may be due, in some small part, to the power of this book and the searing images it contains.

A graduate of Yale University and Clare College, Cambridge, Hersey had left the comforts of the literary world for the battlefields of the Second World War. Within three years he wrote a couple of non-fiction books based on his war reporting and a novel, A Bell for Adano, which won the Pulitzer Prize. In 1944, The New Yorker published "Survival", Hersey's gripping account of a young naval officer's effort to save his men after their boat had been torpedoed by the Japanese. The young, unknown officer was John F Kennedy.

When The New Yorker asked Hersey to write about the human consequences of an atomic bomb, he spent a few weeks in Tokyo and Hiroshima gathering information and interviewing survivors. Hersey soon realised that this story had never been told before, spent weeks feverishly writing it and submitted a piece full of compassion for the victims of the bombing and heart-rending details of their suffering. The New Yorker devoted an entire issue to the article, and it quickly sold out. The piece appeared as a book a few months later and has been in print ever since.

During the Cold War, the fear of nuclear weapons was ever present, an existential dread that rose and fell in intensity with each new superpower crisis. We now know the US and Soviet Union came perilously close to a nuclear war on a number of occasions, most notably during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Technical glitches and mistakes nearly led to the accidental detonation of nuclear weapons near major urban areas. In 1961 the crash of an American bomber almost detonated a hydrogen bomb that would have incinerated most of North Carolina.

Seventy years after the destruction of Hiroshima, fear of the atomic bomb has largely receded. But the danger hasn't. My new book, Gods of Metal, tells the story of a recent break-in at one of America's most important nuclear weapon facilities. Although a trio of elderly Catholic pacifists were responsible, the security breach revealed the ease with which terrorists might gain entry to the site. There are still 16,000 nuclear weapons in the world – along with about 2,000 tonnes of the weapons-grade uranium and plutonium that could be used to build one from scratch.

Although the risk of a nuclear war is lower today than it was a few decades ago, the risk of a nuclear weapon being detonated by a terrorist group is much higher. For extremists who now celebrate the slaughter of civilians and the destruction of cultural monuments in the name of religion, no other weapon could be as efficient.

In pictures: 70th anniversary of atomic bombing of Hiroshima

Show all 15The fact that a city hasn't been destroyed by an atomic bomb since 1945 seems miraculous. A nuclear apocalypse isn't inevitable, however, and the grim history of Hiroshima need not be repeated. The nuclear arsenals of the US and Russia are about 90 per cent smaller today than they were 40 years ago. South Africa dismantled its nuclear weapons in 1989 and Libya voluntarily ended its nuclear program in 2003. The Iran deal raises hope that diplomacy can again halt the spread of this lethal technology.

So long as a single nuclear weapon exists, so long as the ability to process weapons-grade fissile exists, the risk of catastrophe will, too. That is why Hiroshima remains an essential book, a reminder of things that must never be forgotten – and a glimpse of what might still befall us.

'Gods of Metal' by Eric Schlosser (Penguin, £1.99) is out on Thursday

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies