James Lawton: Alan Hudson's tale offers a lesson in glory and pain

There is a frequently traced picture of Hudson’s fall from the football mountain top

When George Best was confirmed in a sea of mourning as the most tragic hero of football’s Lost Generation, Alan Hudson was in his sixth year of physical suffering.

It goes on today, the 15th anniversary of the evening a car smashed into him on the Mile End Road in east London.

Hudson disputes the police verdict that it was an accident. Legally inhibited, he says that he has solid reasons for his suspicions but agrees, with a shrug of resignation, that they will probably never be heard inside a courtroom.

What isn’t in doubt, however, is that the life that might so easily have slipped away on that roadside, or in the course of a two-month coma and 70 subsequent operations, had come hauntingly close to the highest achievement.

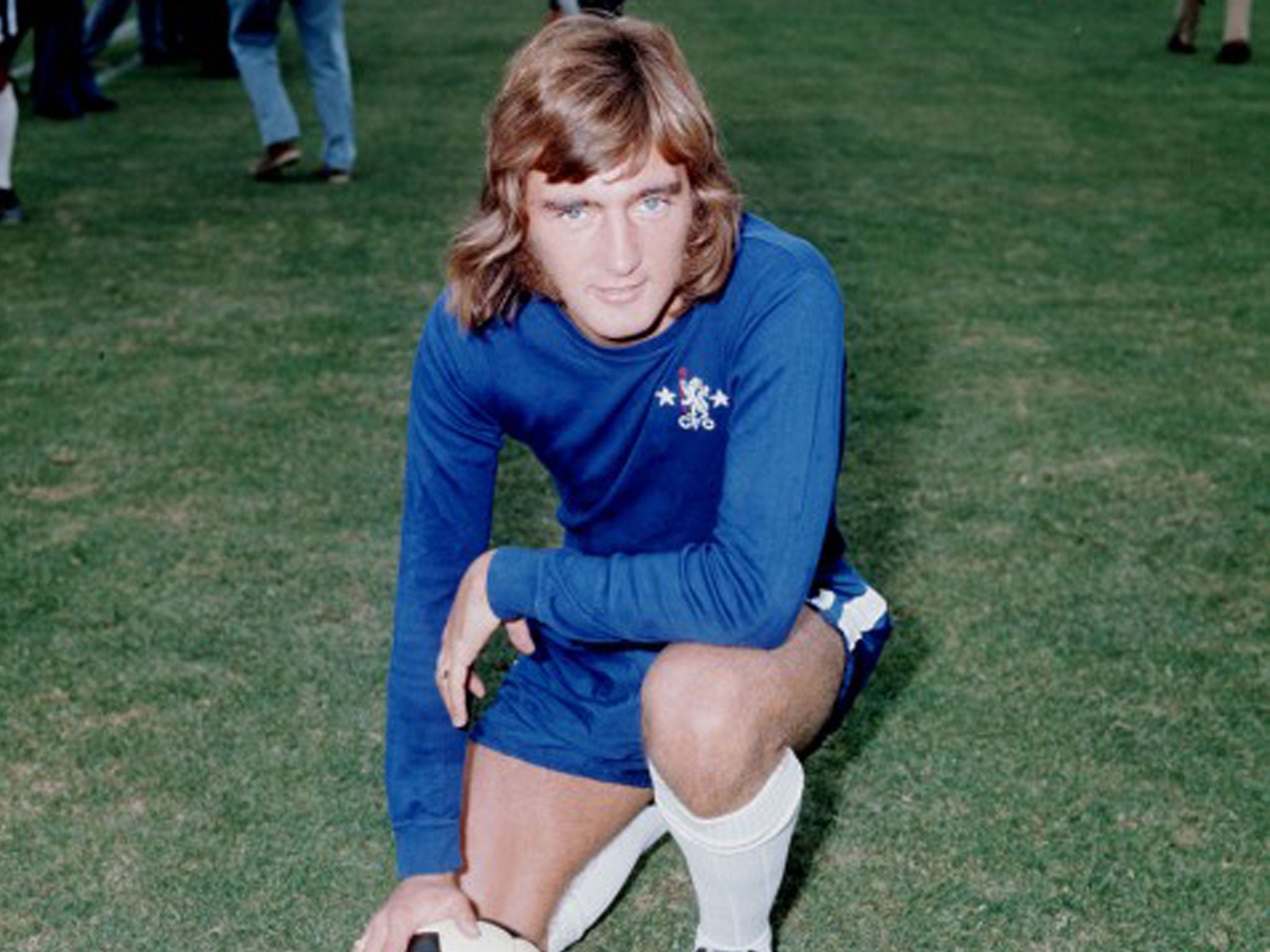

There is a frequently traced picture of Hudson’s fall from the football mountain top. It is of a superbly gifted player who could never draw a line between the pleasure to be found on the field and that in the drinking dens of the King’s Road in the late Sixties and early Seventies.

Inevitably, the split image was provoked most recently by the death of his former manager at Chelsea Dave Sexton, a man of fierce discipline, a Jesuit-educated son of a former boxing champion who fought against the indiscipline of his three most brilliant players, the late Peter Osgood, the mesmerising Scot Charlie Cooke and Hudson, who was reared in a prefab just a short stride from Stamford Bridge.

It is true, Hudson concedes – at least up to a point – as he acknowledges the verdict of Sir Michael Parkinson, who for a while was a despairing friend of Best. Parky said, “Anyone who saw Alan Hudson play when he was young and intact will remember a talent to amaze and will feel sad it was so wilfully squandered. In the final analysis the greatest calamity to befall him is the one suffered only by those greatly gifted people who take their talent for granted. He will never know just how good he could have been.”

He would, though, and over an anniversary drink in the Potters’ Club where he is still remembered as a major reason why the great hoarder of flawed talent, Tony Waddington, came so close to guiding Stoke City to the First Division title in 1975, he picks out from the fog of memory – and pain – those days that he believed shaped the rest of his life.

They came in the spring of 1970 when he collected the ankle injury that changed the way he played – and demanded regular cortisone jabs until the end of his career 15 years later. “Everything was before me and then I got the injury which, looking back, changed everything. My drinking went on to another level. You see, I felt like a kid who had gone to bed on Christmas Eve and seen all the toys wrapped up and then woke up in the morning and they had been taken away.”

What had been removed was his place in Sir Alf Ramsey’s World Cup squad for Mexico – and a role in the epic and violent FA Cup final and replay with Leeds United. He was 19 and Ramsey had confided, “He is the best young English player I have ever seen.”

Hudson recalls with most anguish watching, with one of many drinks at his side, Ramsey withdraw Bobby Charlton in the second half of the quarter-final with Germany. England were in control and in the withering heat the manager wanted to protect a key player who, as it happened, was playing his last international game. “I had this strong idea that had I been there Alf would have sent me on. He wanted someone to hold the ball when he could – and also prevent Franz Beckenbauer breaking out – and I believe that would have suited me perfectly.”

Of course, he had his glories. In the following spring he was influential in Chelsea’s Cup-Winners Cup triumph and in 1975 he made two appearances for England under Don Revie. England beat the world champion Germans with some style and one of the spectators, the gifted midfielder Gunter Netzer asked, “Where has England been hiding this player?”

By then he was playing for – and drinking with – the great man in his football life, Waddington. The break-up with Chelsea was bitter and the wounds never healed, even though he made a brief, injury-plagued return to Chelsea before moving back to Stoke to help them avoid relegation in the last days of his career in 1985.

“My father taught me football and I arrived at Stamford Bridge just about ready to play,” he says. “But it was never going to work with Dave [Sexton]. I respected him as a man but he was very set in his ways and I couldn’t understand why he didn’t see the value of easing up a bit on people like Ossie and Charlie and me. We gave him everything we had on the field and, rightly or wrongly, I thought we deserved a little bit of leeway but it was never going to happen. On one foreign trip we said to Ron Suart, the assistant manager, we wanted a meeting with Dave to talk things through. Ron went up to Dave’s room and told us he would be down in half an hour. It could never go anywhere after that.

“I don’t have any feeling for Chelsea any more. I went to a game not so long ago and afterwards I saw Roman Abramovich leaving. He was surrounded by about 12 minders as he got into a limousine. As I got on to the bus, I just thought, Chelsea has got nothing to do with me anymore.

“It was my club for so long but when I left they wouldn’t give me my five per cent share of the transfer fee. They said I had asked for the transfer. All I cost them was a pay packet that was never more than £150 a week. When Chelsea went to Moscow for their first Champions League final I did think some of the old players might get a ride. I thought, well, no Chelsea player could ever have been more locally identified with the club than me.”

Now his spiritual home in football is Stoke, where he spends much of his time. “No one understood me better than Tony Waddington. You could play for Tony because he loved skill – he brought so many great players to the place, starting with Stanley Matthews, and one of my regrets is we could not deliver him the title in 1975.

“On the Easter Monday we were due to play Liverpool after two matches in London and on the train home I told him I couldn’t play a third game on those hard pitches. My ankle wouldn’t take it. He said to report for the game, the pitch would be fine. He got the fire brigade to turn on the hoses. Before the match Kevin Keegan said, ‘This pitch is amazing, the sun was shining back on Merseyside and how far away is that?’ I told him we got a lot of rain in Stoke.”

Stoke outplayed Liverpool and after the game Bill Shankly, who had recently retired as the Anfield manager, went into the dressing room to tell Hudson he had produced one of the finest individual performances he had ever seen.

It was one of the better memories as Hudson picked up his crutches – his latest operation on an ankle has left him in considerable pain – and got on the London train for a visit with his granddaughter.

He says he is rewriting his autobiography, The Working Man’s Ballet, and that it will not be laden with self-pity. He may, however, be pardoned for a passing thought that sometimes the margins between glory and pain, life and death, can be rather fine.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies