James Lawton: Why the beauty and pain of South Americans' game always guarantees emotion

From Pele's triumph in 1970 to Socrates' despair in 1982, no other nation comes close to matching Brazil's unbridled passion

If they tell you at Wembley that Brazil are not what they were, if they point to the world ranking of 18th and sigh that nothing lasts for ever, tell them that some things do.

Things like beauty and pain, like the cries of joy and anguish which rise up in the shanty towns and streets of Rio and Sao Paulo every four years and which are not so much about the changing patterns of form and luck but an unbroken understanding of the meaning of Brazilian football.

No, it is not all about those surges of brilliant team development and competitive character which currently see Spain in a class of their own, or the intrusions of nations like Italy and Germany and Argentina which, from time to time, have challenged the Brazilian assumption that a record five World Cups is no more than the most basic evidence that their game will always be, in its brilliance and willingness to take risks, quite separate from the aspirations of every rival.

It may be true that this evening we are unlikely to feel anything like the full force of Brazilian seduction, not with the restored coach Luiz Felipe Scolari at the first stage of his attempt to repeat his achievement of 2002, when he astounded a doubting nation and a sceptical football world with a fifth global triumph.

Then, Scolari rode the force of Ronaldo's desire for redemption from a disaster in Paris four years earlier and guided the least imposing of Brazilian contenders beyond the challenge of Germany in Yokohama. On Wednesday he will be hoping that Ronaldinho, a boyish virtuoso in Japan, shows signs that he too can find some of the remnants of his past before his own World Cup crowds next year, when he will be 34. Maybe, too, the fragile genius of Oscar will excite the Brazilian pulse. There is also a certainty. It is that in one way or another Brazil will provoke unique emotion. It comes from the most heightened ambition any nation has ever brought to the arena of sport.

The great motor racer Ayrton Senna believed to the very moment of his death that he had God on his side and as for Pele, who still represents the standard against which every footballer, yes, even Lionel Messi, has to set himself, there was the implicit belief that he had resources enough of his own.

Of course, there is a fault line that, with the exception of 1970 when Pele's Brazil, and Tostao's and Gerson's and Jairzhino's, won the World Cup with a sublime authority which is unlikely ever to be touched again, always threatens Brazil's ability both to confound and enchant the world.

When a convulsion comes it is as though all the light has gone. When Garrincha, the "Little Bird" who was so mesmerising in the 1962 triumph in Chile, died in an alcoholic fog 21 years later, the mourning seemed like the wrenching of a city's soul when the funeral cortège made its way from the Maracana Stadium to his hometown of Pau Grande. Someone painted on a wall, "Obrigado, Garrincha, por voce ter vivido – Thank you, Garrincha, for having lived."

Indeed, for Brazil there can be no more exhilarating gift than the life of a great footballer or the emergence of an exceptional team and when it is withdrawn, in life or on the field, the impact is invariably haunting.

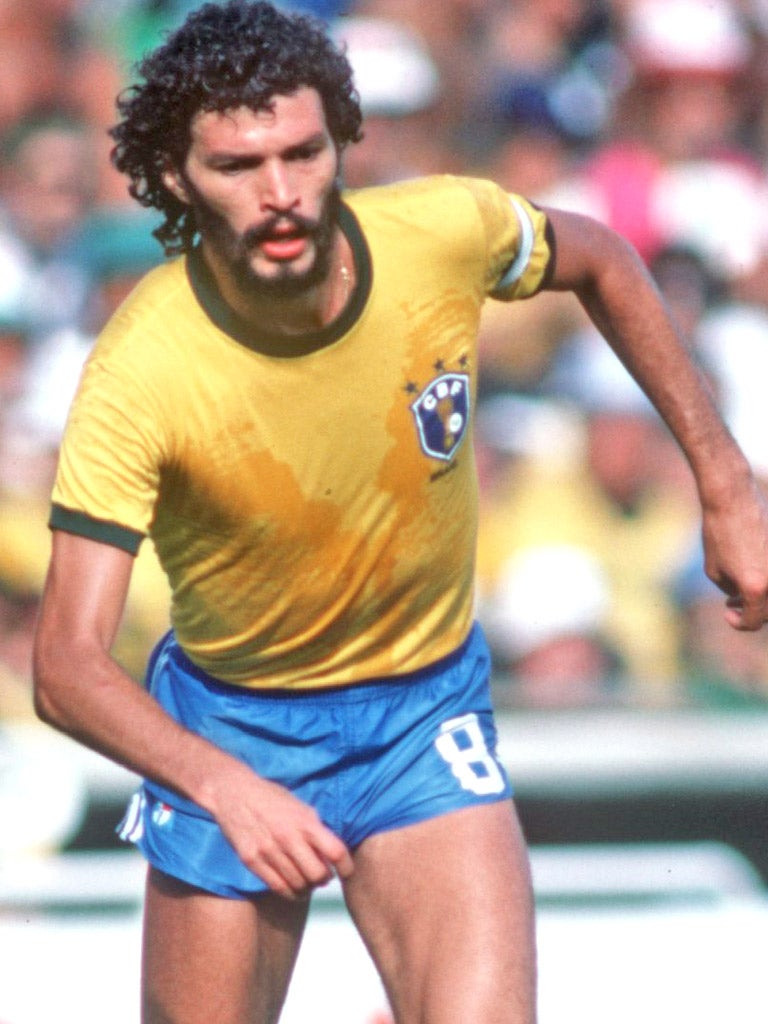

If you ever had any doubt about this you needed to be Barcelona in 1982 when the team of Socrates and Zico and Roberto Falcao – one that many believed might just rekindle some of the coruscating hauteur of 1970 – was ambushed in the Sarria Stadium by Italy. It also helped if you had earlier been in a hill town above the city when Brazil threw open their training session to the local youth.

The pueblo had never known such a fiesta and it was interesting to be in the company of the former Dutch captain Rudi Krol, who four years earlier had suffered a bitter World Cup final defeat against Argentina in Buenos Aires.

He sipped a glass of wine and said, "It is painful not to be competing in this World Cup but then you see something like this and you are reminded of what the game can mean, how it can move people. I will always believe we should have won a World Cup and I think we would have been good champions but then you see this Brazilian team, this latest one, and it just lifts you up when you think you have been competing at this level. I guess the Brazilians will always have this ability to push back all the possibilities."

That seemed like the most reasonable speculation in those days when the great boulevard of Las Ramblas was filled with the sounds and the rhythm of Brazil, when the samba was danced on the café tabletops and Socrates, the tall, hard-drinking, chain-smoking doctor led his team out against the Italians and the drums began to beat and the yellow banners opened up like so many giant sunflowers. Inconceivably, Brazil lost 3-2, a victim of their most reckless self-belief – a draw would have ensured their progress – and the killing precision of Paolo Rossi.

Shortly before he died, at the age of 57, Socrates said the failure of 1982 would always be a mystery, but then in football, as in life, there would always be uncertainty. Who would know this better, we might reflect at Wembley, than a Brazilian footballer who came so close to the ultimate glory?

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies