Sam Wallace: Check the facts Arsène, playing Sweden is far from a gimmick

Talking Football: A November friendly is as good a time as any for Hodgson to test his strength

The England side that played the first international match at the Rasunda Stadium in Stockholm in May 1937 does not, to modern eyes, feature the kind of names that stir the imagination in the way that the post-war team of Billy Wright, Stan Mortensen and Tom Finney do.

The team of 1937 lost most of their careers to the Second World War although the captain, George Male, was one of a few who played in Herbert Chapman's great Arsenal side of the 1930s. Otherwise this was a side whose best years would be spent playing in unofficial wartime leagues or, as many of them did, as physical training instructors in the Armed Forces.

The uncertainty of their lives, not to mention their football careers, was encapsulated in the fate of the Stoke City striker Freddie Steele, who scored a hat-trick in a 4-0 win for England that day in 1937, and retired two years later with a chronic knee injury and depression. He made a comeback only for his career to be interrupted by the war.

Ten years later, the England team of Mortensen, Finney and Wright came to the Rasunda and beat Sweden 4-2. That time there was a hat-trick from Mortensen in a team that included Finney, Wright, George Hardwick, Tommy Lawton and also Neil Franklin, the Stoke defender who defied the Football Association to play professionally in Colombia.

By then, the modern footballer was changing. He was rebelling against the maximum wage and football's reactionary authorities. The star of the Sweden team was Gunnar Nordahl, who was forced by arcane Swedish rules to forfeit his international career when he moved to Milan. These men were less prepared to be kept in their place.

The 1937 game was the first international game at the Rasunda Stadium and the Swedes recognise its significance. Speaking to a spokesman at the Swedish football association (SvFF) last week, he said it made perfect sense that the first game at the newly-built £260m Friends Arena in Solna on Wednesday should be against England.

The last game in August at the soon-to-be-demolished Rasunda was Sweden v Brazil, in honour of the 1958 World Cup final. But the first game at the Friends Arena just had to be England.

Why does this matter? It matters because Sweden are a relatively small but important football nation whose history is intertwined with that of English football. And when one says intertwined, we are not just talking about Sven Goran Eriksson and one notable former member of the FA's secretarial staff. We are talking about the flow of Swedish players into the English game, and the games between the two countries.

It is fitting that the England team plays a role in a hugely significant day for Swedish football upon which they open their new national stadium. Just as Brazil came to play the first full international game at the new Wembley Stadium in 2007, so it is right that, injuries permitting, Steven Gerrard, Joe Hart et al should follow in the footsteps of Male, Wilf Copping, Ted Catlin and poor old Freddie Steele who played at the first game in the Rasunda.

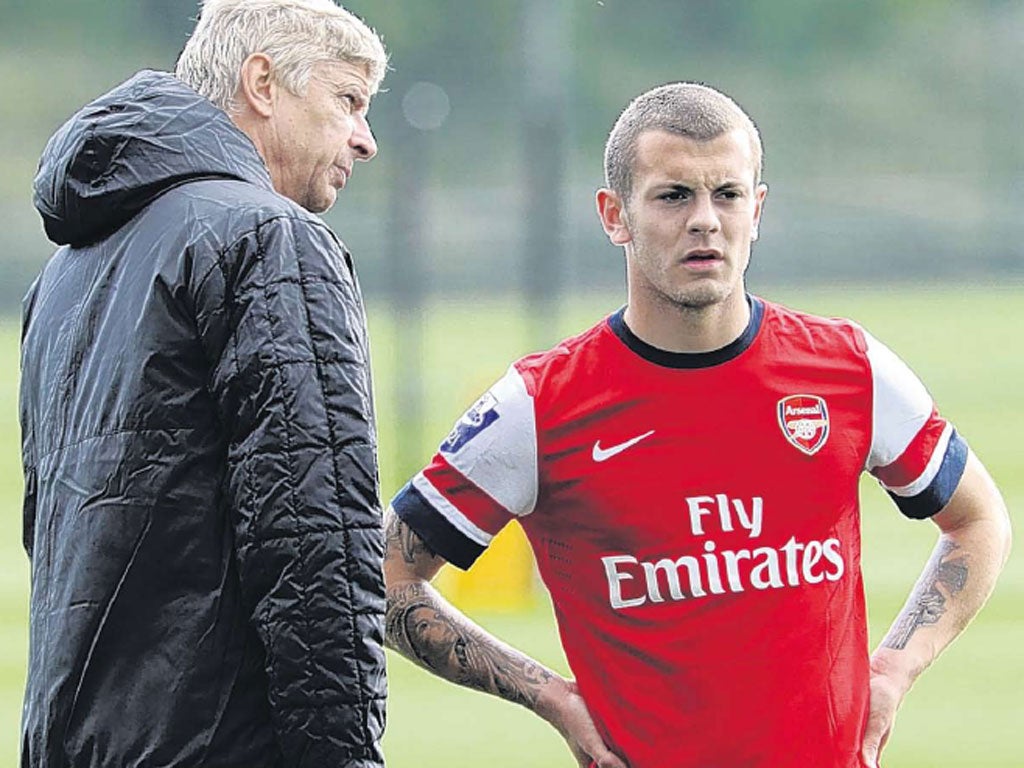

Not all agree, including Arsène Wenger who, for all his many qualities, is a habitual sneerer at international football. "Basically, there are a lot of politics behind these games," he said last week in reference to the Sweden friendly on Wednesday, irked by the inclusion of Jack Wilshere. "When you see some teams travelling during that period, you think it is more to pay back some corporation rather than preparing a team for the next official game."

He is certainly right about many of the fixtures played by Brazil, whose federation will fly the team just about anywhere for the right price. But Sweden v England? The countries have played 23 games since the first in 1923. It is hardly a gimmick.

As for the money-making, the FA in this country is a not-for-profit organisation. It ploughs everything it makes back into the business of developing football at all levels. Whether it does so successfully or not is a whole other debate but then so too is the question of whether Arsenal's well-remunerated executives are making the best use of their club's finances.

The regular howls of anger from managers, and not just Wenger, about international friendlies are tiresome. The powerful European club lobby has already overseen the abolition of the August friendly, with next year's the last in a Fifa calendar. Now some are sniping at the November friendly because, in Wenger's logic, it is too far from the next set of qualifiers to be meaningful.

International football is always, to a greater or lesser extent, a snapshot of a country's resources. It is not like a club's league season, in which injuries and availability even themselves out over the course of 38 games. International football is in part about improvising with whoever is available at any given time and mustering them into the kind of system and vision a coach has for his team.

In that sense, even with last night’s withdrawals from the squad, a November friendly is as good a time as any for Roy Hodgson to test the strength of what he has. The picture will be different when England play Brazil in February and then different again in March for the World Cup qualifiers against San Marino and that crunch game against Montenegro in Podgorica. Each time, an international manager must make the best of what he has.

Hodgson happens to be a huge figure in Swedish football, not least for his 1976 title-winning season as a rookie manager with Halmstads and then his five championships in a row with Malmo between 1985 and 1989. He and his friend Bobby Houghton, Malmo manager when the club lost the 1979 European Cup final to Nottingham Forest, are regarded genuinely to have revolutionised Swedish football.

Many of Hodgson's Malmo players went on to be part of Sweden's 1994 World Cup side that finished third, arguably the country's greatest ever team. It is just another reason that those of us who love international football and its history think it is right for England to be in Stockholm this week. And just like 1937 or 1947, it would not hurt for England to play well and win the game, given the challenges they face in the spring.

Gerrard's ton is still quite a feat

The England team has played 914 games since the first in 1872 and to play in 100 of them is some achievement; one that can be measured by the fact that only five have reached that milestone. Come Wednesday, Steven Gerrard will become the sixth. True, he has never won a trophy with England, but then only two of the five centurions have. That he reaches 100 as captain is testament to his enduring quality.

Rangers hit by high hopes

Queen's Park Rangers' home league game against Southampton on Saturday has taken on even greater significance after QPR's seventh defeat of the season against Stoke City on Saturday. Between them they have only nine points after 11 games and both managers are feeling the heat. The difference is that Southampton have come up two divisions in two years and have, give or take a few, a Championship-standard side. QPR's excuse is not so obvious.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies