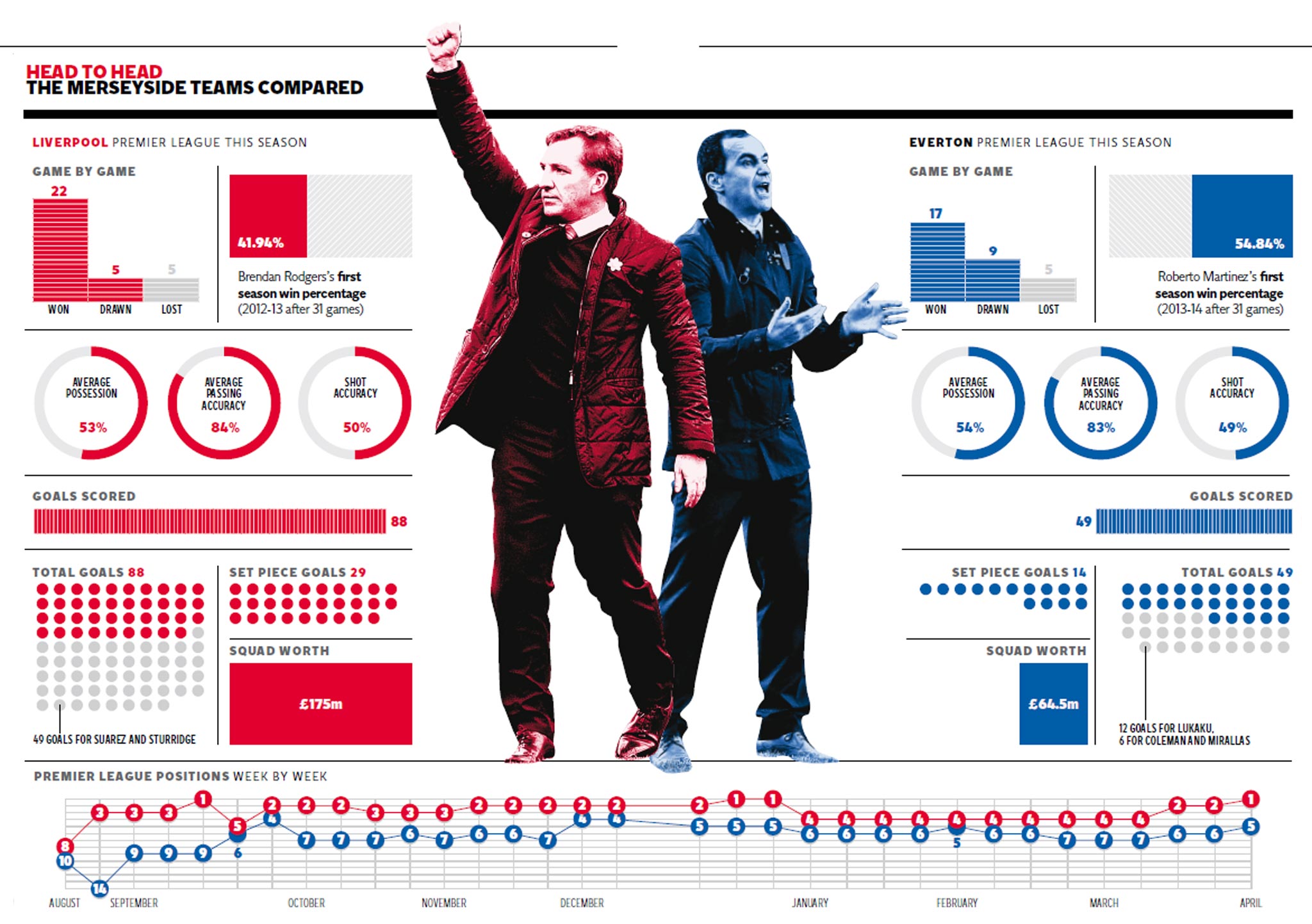

Liverpool manager Brendan Rodgers and Everton's Roberto Martinez are returning merriment to Merseyside

Twin motivators with positive outlooks are restoring their clubs’ reputations and bringing new belief to their players

On the banks of the Mersey, thoughts are turning back to the 1980s in myriad ways.

The extraordinarily powerful testimony delivered to the new Hillsborough inquest in the past week has awakened the memory of those days, only with the sense that the legal system will this time grant the 96 people who died a proper duty of care.

And suddenly the football seems to belong to that time too. Not since the 1987-88 season have Liverpool and Everton both finished a league campaign in the top four and the final table then had a complexion that Merseyside is beginning to feel it might just assume once more. Liverpool champions. Everton fourth.

Though Merseyside didn’t know it at the time, 1988 was the beginning of the end. Howard Kendall had just left Goodison Park and Kenny Dalglish would walk out of Anfield soon after, in 1991, traumatised and broken by Hillsborough’s emotional toll.

What currently lifts the mood around the place more than anything is the sense that this is the beginning of something new. The city of Liverpool, with its rich sense of romance, steeped in the inspirational powers of Shankly, Paisley, Fagan, Kendall and Dalglish, finds itself blessed with two of football’s supreme motivators and optimists. Brendan Rodgers and Roberto Martinez do not deny the significance and influence of money in football but they share the philosophy that the manager’s task is to make a team technically and psychologically proficient.

“Feeling comfortable with ourselves,” as Martinez put it yesterday, as he prepared to receive Arsenal at Goodison on Sunday and make big strides towards displacing Arsène Wenger’s side in next season’s Champions League.

There was no better example of Martinez’s capacity to imbue a player with new belief and ambition than a story he told of how he had taken Leighton Baines with him to see Manchester United play Bayern Munich in the Champions League on Tuesday night as part of his attempt to develop the left-back as a central midfielder in the mould of Bayern’s Philipp Lahm.

“I always thought that Leighton could develop into Lahm’s role. It is in his make-up,” Martinez said, reflecting that the German’s qualities – low centre of gravity, good technique, good on the ball, strong in “one v one situations” – are perfectly applicable to Baines. The Englishman “is such a deep thinker, someone who can take these instructions to a different level,” Martinez said – and the more fundamental point of his story seemed to be his belief that players can be allowed to stop believing they can develop.

“They can stop performing when they reach a certain level because there is nothing new to achieve,” Martinez added. “The way we are developing young players in the British game is very strict. It is very black or white, but football is not like that. Football is a game of errors, you need to react and adapt, you need to be flexible and it is very important to have players like that in your squad. It comes from having that flexible mind and playing different systems, rather than occupying the space and just being solid in your role.”

These were the words of a manager who, 10 years ago, took his Swansea City side, then in football’s third tier, to see Barcelona play Celtic in the Uefa Cup, in the belief that they would learn to play that way. Baines, who appeared to have no choice in the matter when it came to visiting United with the boss, must consider Everton’s refusal to sell him to David Moyes more of a blessing by the day.

Here is football management at its most sophisticated. It was Rodgers who said last year that “you train dogs but you coach players” and the results of the self-empowerment are felt throughout Everton, which once feared the so-called top four, and in the Moyes era never beat them away. Now Martinez wants to take the step. “Only once in the last 22 games against Arsenal have we scored more than one goal against them,” he said.

Everton have been at this threshold before. At the corresponding weekend last season they were four points behind Arsenal, in sixth place rather than fifth now. We will see if they make the next step but their ability to do so is contingent on their mentality, Martinez said.

Across the city, Rodgers has the bigger challenge, seeking to meet monumental expectation that his Liverpool side can be champions, at a time when Manchester City seem to duck beneath the spotlight.

Rodgers spoke a similar language, discussing ahead of Sunday’s visit to West Ham how the team’s “belief on the ball and belief they can win games” are what he has changed. Last weekend’s 4-0 victory over Tottenham was the biggest psychological victory of this season, he said. His back four are certainly vulnerable but he wants the same from them that Martinez sees in Baines. “I don’t want rash defenders but defenders to work with intelligence.”

The city beyond Melwood and Finch Farm can only wait and hope, though a final table like the one in 1988 will have a profound effect on a city which has not enjoyed the artificial boost to its economy which football has delivered to Manchester. That city was blessed with the 2002 Commonwealth Games, the landmark stadium of which became a subsequent home to Manchester City and lured in Abu Dhabi billions.

Old Trafford – which spotted football’s commercial opportunities far earlier – has had the adjacent land to allow development which Liverpool has lacked. The club continues to inch towards an expanded stadium within cramped confines, while Everton’s search for serious investment has been frustrated by the rejection of plans to take them out of town.

Sara Wilde-McKeown, chair of the Liverpool region’s Visitor Economy Board, said that two Champions League clubs would have a profound economic effect. “It would flatten out hotel trade across the week, effectively extending the peak trading time,” she said, while Nigel Hibbert, investment director at Quilter Cheviot investment managers, said that a single round of European ties at Goodison and Anfield could inject millions into the local economy through visitor spend. “Tourism is already worth £3bn a year to the regional economy and the success of the clubs will only add to this.”

Jon Brown, director of Paver Smith, the PR and marketing agency which works with Liverpool City Council, said Champions League football for both clubs would “turbo-charge the tourist economy”.

Even on a chill Friday morning with no game ahead, Liverpool’s souvenir shop was packed with 50 Thai visitors and Martinez senses the chance of some of that for his club. “Champions League football changes external perceptions,” he said. “You could get an overseas investor overnight. That could happen.”

You felt that he had been imagining how he would have set about a Bayern home leg at Goodison. He said that it would be “very cheap” to analyse publicly how he would have played them, thus inviting inevitable comparisons with David Moyes’ defensive approach.

However, his response when reminded that he has said he would never change his attacking footballing principles was revealing. “No,” he replied. “Never.” He would have had a go against the Germans.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies