James Lawton: Voice of Racing tells it straight from his old horse's mouth – thoroughbreds are born to run

O'Sullevan's point is that the most reluctant participants in a world without the Cheltenham Festival would be characters like Attivo

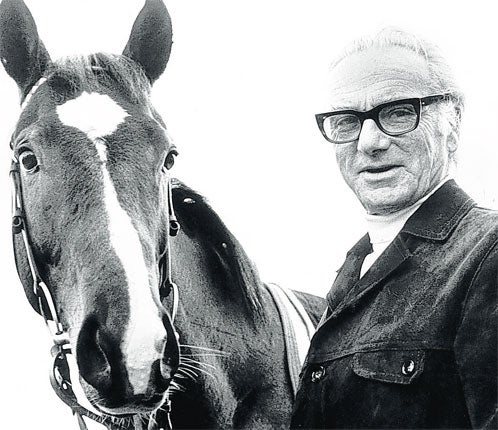

When Sir Peter O'Sullevan arrives at Cheltenham this week, having at the age of 93 driven down briskly from his flat in Chelsea, there is a very good chance he will be confronted by something rather less than he would desire.

It will be someone carrying a placard in the shape of a tombstone and bearing the name of one of the 32 horses who have died at the course over the last 10 years.

This will not be a meeting of minds. Sir Peter, one of the most relentlessly courteous men on earth, is unlikely to engage in any ferocious public debate but his defence of the greatest jump meeting of them all is no less intense or resolute for this.

When you outline the case of Animal Aid's horse racing consultant Dene Stansall, one of O'Sullevan's deepest regrets is that his beloved Attivo, winner of the 1974 Triumph Hurdle is no longer able to join in the conversation.

"I know what he would say," O'Sullevan declares. "He would say, 'For heaven's sake, don't stop me racing.'" Such a viewpoint is unlikely to deflect the protests which will be expressed by 32 "tombstone" bearers and rotating eulogies for the fallen thoroughbreds.

Animal Aid announces: "We will be at Britain's most notorious death trap for racehorses to remind punters of the horses who have died at Cheltenham over the past decade. Sadly, horses are continuing to die in large numbers around the country.

"The British Horseracing Authority refuses to name or keep public count of these horses, so Animal Aid has taken on the role of bringing the truth to the public's attention. We look forward to the day that events such as the Cheltenham Festival, which put profits before animals' lives, are a thing of the past."

O'Sullevan's point is that the most reluctant participants in the new animal Utopia would be characters like Attivo, whose relish for running and jumping at this time of year in the valley in the Cotswolds brings an edge to life, a recurring reason to marvel at the courage and nerve of both horses and men, that is as deeply thrilling as it is unique.

Nor is this self-evident reality compromised by the ambivalence which is bound to come to even the most gung-ho enthusiast whenever they have to put the screens around a stricken horse and call for the vet.

Where O'Sullevan separates himself from protesters most emphatically is in their failure to understand the nature of the thoroughbred – and what he considers a hopelessly arbitrary set of priorities.

It happens, for example, that over the last decade or so the former Voice of Racing – who famously called without a hint of emotion the result of that Triumph Hurdle – has sent a steady stream of financial support to animal welfare through his Charitable Trust.

Among the six principal beneficiaries is Compassion in World Farming, which says: "Sir Peter's donations have been a real lifesaver, helping to jump-start the international campaign to halt the global growth of factory farming and to end the massive trade in long distance transport of farm animals."

O'Sullevan says: "There is no doubt we must stop abusing animals in the way we do. I feel the way we human beings treat animals is comprehensively unacceptable in every conceivable way. The way we farm them is becoming more and more unacceptable.

"Billions of chickens haven't got room to move. They have no more than a pocket handkerchief of space during their short existence. Horses being transported from Poland and Lithuania to the toe of Italy to be 'topped' is just appalling."

He says that the thoroughbred racehorse is by some distance the aristocrat of the animal world and, whenever the issue of whether he should race and jump or not is raised, always his thoughts go back to Attivo.

"When he was racing," O'Sullevan recalls, "Attivo was an absolute joy to be around. I would drive to see him at every opportunity and I was always filled with the greatest anticipation. You couldn't imagine a creature more alive and enjoying his life so much.

"Then he stopped racing and I put him out to his Elysian field, his great reward, and, you know, he became the most miserable bugger in the world. Every time he looked at me there seemed to be reproach in his eyes. It was as though he was saying, 'What have I done? Why are you punishing me?'"

The O'Sullevan trust has helped in creating better conditions for horses working brick kilns in Egypt and provided a way-station in Pakistan. He can still rage over the decision of a regiment of cavalry to leave their horses in Cairo, because of the cost of transport, when it returned home, and how the horses were sent off into the desert to die, without water and any other care.

"Animal welfare is a huge issue and I warm to all those who care about it," he adds. "But, no, I don't believe we have a problem of cruelty or neglect at Cheltenham. There are accidents, of course, and every one of them is regretted but where would we be if everything, however fine, was scrapped because there was an element of risk?"

It is a point he will not address directly to the men and women carrying the tombstone placards this week because there are some arguments you can never win – even with the help of a debater as formidable as his old mate Attivo.

Cheapjack cricket, day after day, has worn out Strauss

If andrew Strauss some time soon confirms the rumour that he has had enough of one-day cricket, its insane pursuit of the slow buck, we can only hope it sparks some reappraisal by the people who run the game.

We're not talking about some public relations-driven review of the current format of the World Cup, which is already under way in the form of the pruning of associate nations who have from time to time so enlivened matters, but the demands on seriously minded and talented cricketers like Strauss.

No doubt there are places for shortened forms of the game in the 21st century but their current, cheapening importance surely has to be cut back if cricket is to hang on to a competitive integrity already bludgeoned by cheating scandals.

When Strauss was leading England to Ashes victory he was the embodiment of a committed, intelligent captain who was also capable of outstanding achievement. Now he looks time-expired, frustrated and wondering about the point of it all.

Around the peak of his career the great Brian Lara reported how his love of the game was simply being burnt away. We didn't have to waste too much time identifying the problem. It is the same, you have to suspect, with Strauss as it was Lara: too much cheapjack cricket.

Lièvremont may have lost his head in turning on team

There are two great crimes a coach of any sport can commit. One of them is repeatedly to meddle with his team, and so erode its self-belief, and the other is to heap blame on his players when things go wrong.

In the wake of the heart-warming victory of the Italian rugby Azzurri, French coach Marc Lièvremont has to be found guilty on both counts. He also added another pinch of insult: the charge that his men were cowards.

"There is a certain form of cowardice," he declared in Rome. "When I speak to them, nothing happens – as usual. Some of the players maybe wore the French jersey for the last time." Some critics believe they hear the sound of Madame Guillotine clanking her way to the Stade de France in anticipation of possible disaster at the hands of Wales at the weekend. Someone will probably have to tell Lièvremont that it is him she has in mind. Who cannot say it is hardly before time?

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies