Battle for doctoral funds: Should government cash for PhDs be restricted to the best universities?

In the university world, differences of opinion are nothing new. But the outcome of this one might just change the character of higher education itself. Universities are at odds over the future of postgraduate study, with a Government review on the subject, due to report in the spring, setting up sharply diverging views on how PhDs should be funded just as finances for the sector as a whole come under huge pressure.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the argument comes down to a battle between different types of university, with the older, more established institutions making a case that ministers should favour them over their newer rivals for Government funding of doctorates, currently estimated at £200m. The newer universities, including former polytechnics, some of which have been keen to develop their PhD work, are understandably opposed.

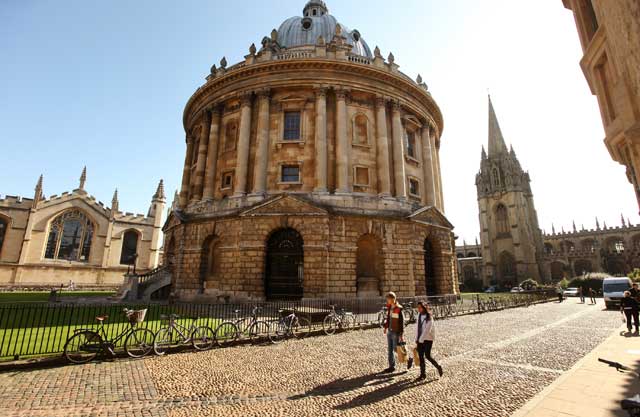

The dispute centres on a paper produced by the 1994 Group, which represents 19 universities including Durham, Exeter, Lancaster, Sussex, York and five London University colleges. It is one of two groups representing "old" universities. The other, the Russell Group, speaks for 20 institutions, including Oxford and Cambridge.

The inquiry, into postgraduate education was set up last summer by the Business Secretary, Lord Mandelson, and is being led by Professor Adrian Smith, director general of science and research at the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills.

The 1994 Group's paper comes up with a measure of the "productivity" of each university in producing PhD papers, and builds a case that Government funding should be concentrated in the most "productive" institutions.

Using data from the 2008 Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) submissions and the Higher Education Statistics Agency, the paper devises an indicator whereby the total number of doctorates completed at each university among 89 UK institutions is compared to the number of staff at that university who are required in their contracts to work with research students.

This results in a statistic, for each university, of the number of doctorates produced per 100 members of staff. Universities are then ranked.

And the results? Well, the paper acknowledges that Oxbridge is in a category by itself at the head of the field: Cambridge comes top with a productivity figure of 52.3, followed by Oxford on 45, with Imperial College London in third place on 35.7.

But crucial to the paper's argument is what happens next: all 39 Russell Group and 1994 Group universities are in the top 41 institutions in this ranking, with "productivity" dropping off sharply between places 41 and 42. Productivity on this measure falls from 14 doctorates per 100 members of staff at ranking 41 to eight at ranking 42, a natural "cut-off point" in the index, says the paper.

The remaining places are filled by universities which are represented by the University Alliance and Million Plus. These are mainly former polytechnics.

The paper also presents figures showing that, in terms of the number of PhDs completed at each university, the Russell Group and the 1994 Group are again well ahead of their rivals. Analysed by subject area, the comparisons produce a similar result. Remarkably, perhaps, Oxbridge alone produces more doctoral theses every year in subjects including humanities, physical sciences and mathematical sciences than all of the universities in the Alliance and Million Plus combined.

The paper does not advocate changing the way that taught Masters courses are funded, saying it is a "mass-market activity and should be supported at all universities".

But it concludes that the statistics demonstrate the need for a change in the way PhDs are funded. Instead of the Government funding doctorates wherever they are taken, as now, it would only pay for those that come above a certain "quality threshold".

"There are three levels of the market in PhD provision," it says. "Oxford and Cambridge have an extremely strong and unique profile. The institutions of the 1994 Group and the rest of the Russell Group are very strong and productive. Non research-intensive universities of the other mission groups show far less productivity and volume of PhDs."

Although the paper holds back from saying explicitly that those universities below the "cut-off" point on its indicator should not receive Government money for PhDs, it appears to come close. Those not providing enough "quality", it suggests, would receive no cash, but instead should rely on fee income from students.

"A new quality threshold on PhD provision must be introduced," it says. Hefce's funding should be more concentrated than it currently is, in order for the Government's funding to be channelled as effectively as possible and at best value. "This would still allow all institutions to provide PhDs if they wish, but provision below the quality threshold would be reliant on fee income rather than Government funds."

The University Alliance is not impressed with the study's methodology, arguing that the indicator says little that is new. Older universities do have more PhD students, but this does not mean that non-1994 Group and Russell Group institutions do not contribute.

Libby Aston, the Alliance's director, says that Alliance universities deliver nearly 20 per cent of all postgraduate provision, and they awarded nearly 1,200 PhDs in 2007-08 in comparison with just over 3,000 from 1994 Group universities, with many delivered on a more flexible basis and in areas that are critical to the UK economy.

The Alliance also believes that the paper was wrong to analyse "productivity" solely on a university-by-university basis. Aston says that the RAE 2008 results show that there are many well-managed research centres within individual departments which are outside the traditional research-intensive universities. Simply to propose a cut-off for funding for all institutions below the paper's threshold would wrongly hit such departments, she says.

To be fair, the paper stops short of stating explicitly that "productive" departments in universities below its quality "cut-off" should not be funded. But it might be read as implying this.

"The report does not provide sufficient evidence on which to restrict PhD funding to a particular group of universities," says Aston. "As with research funding, the principle of funding excellence wherever it exists remains the best policy."

Paul Marshall, the executive director of the 1994 Group, says that the group is not saying it has come up with all of the answers, or even any of the answers. "We do not, in particular, have a problem with good research departments in universities which are ranked highly in our analysis being funded.

"But the issue here is that, because there is a complete absence of quality thresholds, a lot of Government funding is being distributed across some very poor departments. That's what we want to highlight. The current funding arrangements support the idea that every university can do everything. We, as a group of universities, do not believe that is the right way to go."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies