The six things we learned about Brexit from the Autumn Statement – or why Project Fear was right after all

Had we not voted for Brexit we could have doubled defence spending... or enjoyed many more drinks parties

The point about the Autumn Statement is that it reveals the extent of the “invisible” cost of Brexit. Even though the economy is still growing, we now know how the economy might have grown had Brexit not been voted for. The figures are chilling.

1. Britain will be about £200bn worse off by 2021 thanks to the Brexit vote

Or roughly £6,500 for each worker in the country, cumulatively. It works like this. The Chancellor and the Offiice for Budget Responsibility say that GDP will be 2.4 percentage points lower by 2021 than it would otherwise have been. This is because, for example, industrial investment will be lower because of all the uncertainty (though it's worth nothing that uncertainty is better than the certainty of a hard Brexit and expulsion from the single market). So if the British national income (GDP) is about £1,700bn per annum, and it is going to be about £40bn a year lower on the average than otherwise, then that adds up to about £200bn over a five-year run.

Some 30 million of us work, so that makes £6,000 each cumulatively, or about £1,200 a year in lost earnings and the lost value of public services. To put it in perspective, £40bn is some way ahead of the entire annual defence budget for the UK, and about the same as what the nation spends on alcohol and tobacco. In other words, had we not voted for Brexit we could have doubled defence spending, or enjoyed many more drinks parties.

These numbers are very rough, but we would be well on track to the “Project Fear” Treasury prediction during the Brexit referendum. This was for an annual loss in income per UK household of £4,300 by 2030. In fact, if a hard Brexit is especially brutal, the old Project Fear figure could prove quite optimistic.

2. If we are unlucky, UK national debt will exceed annual national income by the mid-2020s

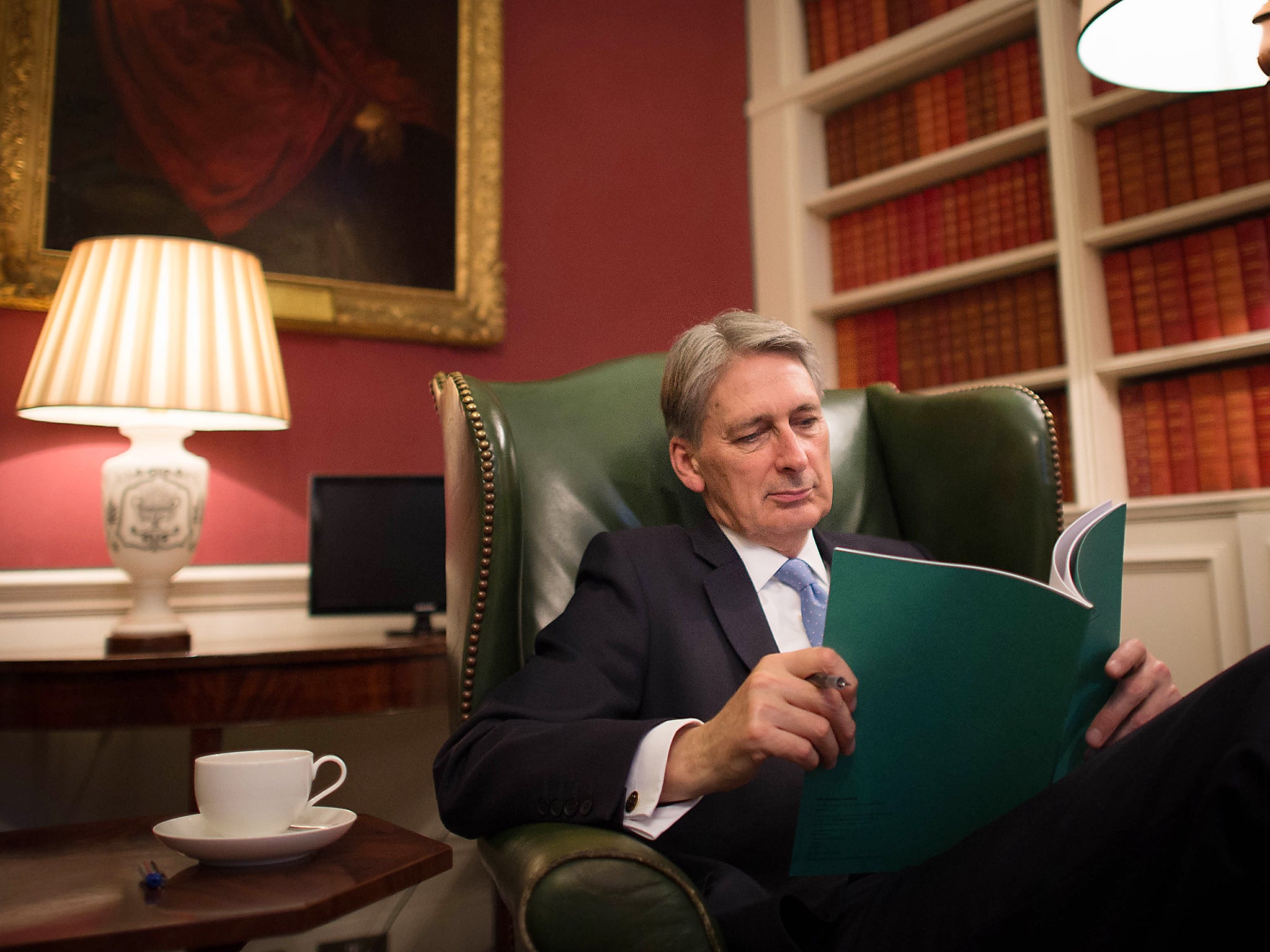

As things stand, on the relatively benign scenario painted by Philip Hammond, the debt will rise to just over 90 per cent of GDP in 2017-18, figures that would once have been greeted with horror by Tory MPs.

Although controversial, there is an economic theory that poses the idea that once national debt approaches 100 per cent of GDP, the burden of servicing it means such high taxes that the economy ceases to grow and, thus, provide the means to continue to service that debt. Then a nation enters a sort of debt death spiral, where Greek-style bankruptcy beckons. Thankfully, the Bank of England is printing the money to pay for the UK’s debt, and it is cheap to service; but this may not be sustainable forever. When interest rates return to more normal levels debt as a percentage of GDP will be high because GDP will be lower than it ought to be because of Brexit. Thus will Brexit have delivered the UK closer to a eurozone crisis. The irony!

3. The Autumn Statement does very little for those at the very bottom of the pile

For those without a wage at all, increases in the minimum, or "living", wage mean nothing. Without a salary of more than £10,000, moving the threshold for income tax to £12,500 also delivers very little too. If you can’t afford car and have no savings, the Chancellor's other smaller measures will also have little impact. More importantly, if the economy is growing more slowly – thanks to Brexit – there is less chance of you finding a job, even though job creation has been impressive in recent years. One small comfort is that Hammond promised there would be no more cuts to benefits in this Parliament.

4. Pensioners should watch out

The Chancellor dropped a fairly hefty hint that the “triple lock” that delivers decent yearly increases in the state pension will be “reviewed” by the next election.

It has succeeded in lifting many out of poverty and allowing some improvement in the level of comfort for those who’ve given their working lives to the country, including the generation who fought the last war. However, that heavy lifting on pensioner poverty has now been done; it is becoming an expensive cost. Had Brexit not holed the national finances as badly as it looks it will, then some better for protection for pensioners might have been provided. It is worth noting that older voters were the most pro-Brexit.

5. If you’re 'just managing' then there is some genuine good news

Families on lower incomes will benefit from the rise in the tax threshold, the abolition of the fuel tax rise, and, if you have a little cash put away, the new National Savings bond. What’s more, the moves announced on gas and electricity bills, on letting agent fees and on improving schools, social housing and the NHS (not convincing to all, admittedly) will also help maintain and improve living standards. However, against this is can be set higher prices as inflation feeds through (a direct consequence of Brexit) and you will also see lower growth in wages. Those just managing, like everyone else, really need a pay rise.

6. A less productive Britain

Hammond is right to say that Britain has a productivity problem and that the key to making sure British workers get higher wages and work fewer hours lies in improving their output to, say, German levels.

The Chancellor announced some worthwhile investments in boosting research and development and in innovation, which should help. However, as any economist will tell you, much the biggest help to raising productivity is access a a large market... such as the European single market.

This permits more and more socialisation of workers, for example, as Adam Smith pointed out 250 years ago. It is true that China and India will soon be even bigger markets than the EU, but will we ever have the same access? If not, then Brexit will severely limit the scope for improving productivity and that means that British workers will continue to work longer hours for lousier pay than their German counterparts.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies