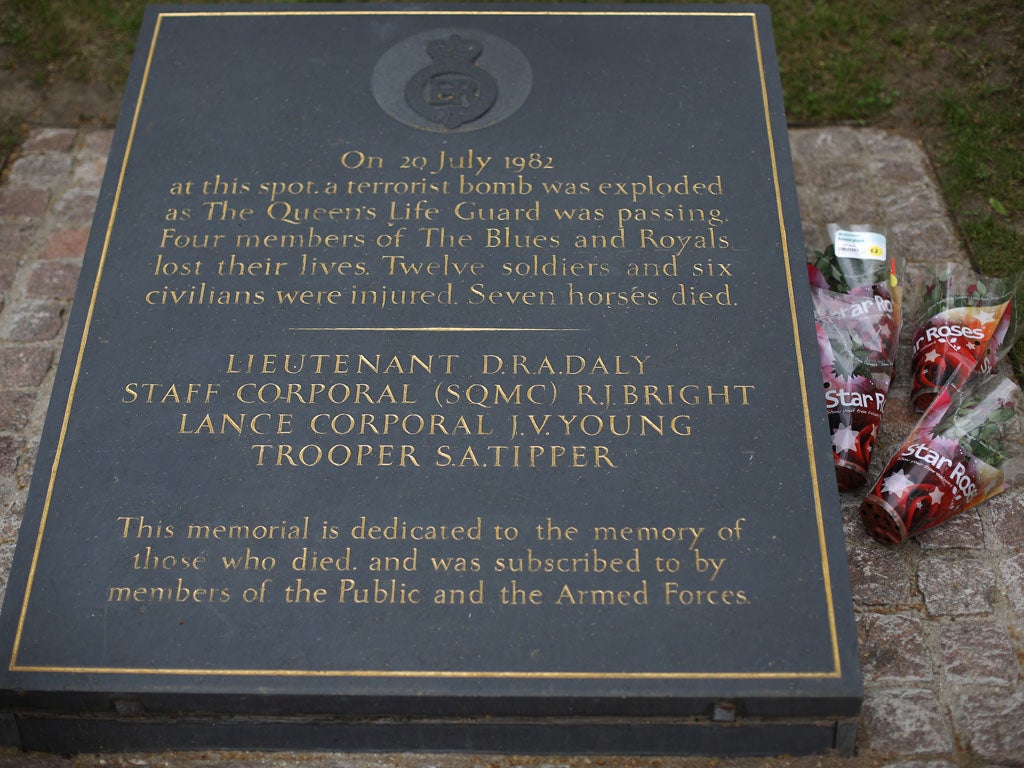

As a key suspect in the 1982 Hyde Park bombing walks free, it’s worth remembering what mediation between once sworn enemies really means

Seeing the world as others see it is a skill Britons have had less need to develop

The release of John Downey, who was a prime suspect for the Hyde Park bombings of 1982 but denied any involvement, was attributed to a “catastrophic failure” by the police. But it is quite hard to discern where exactly that failure lay. Was it in not realising that Downey had been a beneficiary of what amounted to an amnesty for IRA men considered to be fugitives, agreed on the quiet as part of the 2007 Northern Ireland peace process? Or was the error that he was included in that amnesty at all, because of an arrest warrant still outstanding for the Hyde Park killings? Either is possible, or both.

Without that secret agreement, however – under which 187 people considered wanted IRA terrorists were told, in writing, that they were no longer liable to prosecution – the Good Friday agreement might never have been signed, and the violence, in Northern Ireland and the mainland might have continued. Nor is it impossible – whatever is said publicly – that Downey’s inclusion in that list was part of the deal. We shall probably never know. Ambiguity is a crucial part of most peace agreements, especially those designed to bring bitter civil conflicts to a close.

One reason for the outcry in Britain and among Unionists in Northern Ireland – the First Minister, Peter Robinson, threatened to resign yesterday unless the decision not to prosecute the 187 was put to a judicial inquiry – might be that recent British history has been mercifully free of the sort of conflicts that require such ambiguity in their settlements. Northern Ireland was an exception, and one which, despite its duration and its cost, impinged relatively little on the majority of the population. There are many countries – take the Balkans, or the Middle East, to name but two – which are much less fortunate. There, ambiguity is the stuff of almost daily exchange.

If anything is to get done, constructively and in relative peace, there has to be unspoken agreement that the same words are going to mean different things to the two opposing parties. The art of the negotiator is to find those words and generate enough trust on either side that the agreement sticks.

The difficulties that remain in Northern Ireland – where peace mostly prevails, but trust is still in short supply and the hoped-for reconciliation remains elusive – illustrate how complex the resolution of such deep-rooted disputes is. And, if peace is so hard to come by in Northern Ireland, which has stable states as neighbours, this suggests how much more intractable it will be in other, more volatile, parts of the world, where the conflicts have been longer and more brutal, and where the space for ambiguity, let alone compromise, is not at all evident.

I have just finished reading The Fog of Peace, a book by Gabrielle Rifkind and Giandomenico Picco – she a psychotherapist and international relations expert, he a former UN diplomat of an unconventional stamp. They argue that the personal and psychological element of conflicts is too often either ignored or underestimated in the negotiations that must follow, and appeal for would-be mediators to make the effort to get into the mind of the adversaries. Their contention is that the technical has habitually superseded the personal.

They are not starry-eyed – Picco negotiated the release of hostages in Lebanon – and well know how impossible sealing peace can be, let alone embarking on that path. But when they apply their approach to, for instance, Israel-Palestine, talking to the Taliban, to Hamas, to Iran, their view is that the specifics of what divides the opposing parties is too rarely considered beyond the basics of territorial demands. And if the nature of the divide is insufficiently understood, then so too will be the slender chance of finding common ground. Many years ago, I was told that British officials meeting foreign dignitaries – friendly and less so – were supplied, as a rule, with charts that plotted local and global events against the biography of the person they were to meet, as a way of explaining what experiences and influences might have contributed to their thinking. I hope it is still done.

For Angela Merkel, for instance, who will address a joint session of Parliament today, such a chart would show how old she was when the West European campaign against the stationing of US cruise missiles was at its height; when Gorbachev came to power in the Soviet Union, when the Berlin Wall fell. These were particularly momentous events, but people’s age and what they have seen in their lifetime – perhaps also who their parents were and what they experienced – cannot but affect their outlook and, if it comes to that, their negotiating stance.

Being able to see the world as others see it, in all its cultural, as well as geopolitical complexity, is a skill that we Britons – inhabiting a country that has no contested land border and is still living on the last flickers of victory in the Second World War – have had less need to develop than many of our neighbours. But it is one that will be in ever greater demand in this increasingly interconnected world.

m.dejevsky@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies