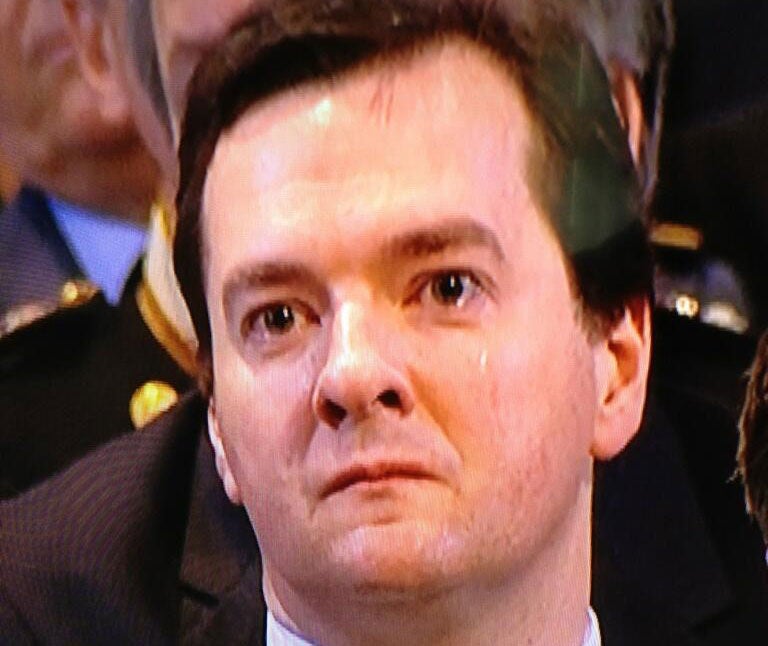

As George Osborne now knows, there’s a great deal more to crying in public than meets the eye

If you can’t weep at a funeral, even a funeral of such pomp and vainglory as this one, when can you weep? Yet Osborne's tears for Thatcher continue to bemuse us

And then, caught handily on camera, two tears rolled down the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s face; that harsh lumpy face, a face like a potato but with the animation, empathy and intelligence of a potato. There it was: “Wallpaper” Osborne, weeping. Some said it showed that Wallpaper had a human side, the implication being that the rest of him wasn’t. Many were bemused by his tears: how could he weep? Some, or at least Tony Blair’s former spin doctor, Lance Price, said that Wallpaper’s tears could “do him no harm”, the implication being perhaps that if he’d thought they could have harmed him, he’d not have wept.

Why he wept, we don’t know. He was 19 when Mrs Thatcher herself wept at her loss of office. Some say his tear ducts uncorked at the reference to her Jesus letter, in which she told a child that she tried to be good but wasn’t as good as Jesus was. Some say they were the tears of the crocodile: a creature which can’t weep, nor even dissimulate weeping; it merely leaks while its teeth rend. Sir John Mandeville described this, some 650 years ago, when he wrote of “cockodrills, that is a manner of a long serpent... [they] slay men, and they eat them weeping, and they have no tongue”.

Mandeville’s cockodrills had no Atos to help, and ours have plenty of tongue to confect lies about benefit fraud and immigrants and shirkers; but, still, the description is oddly resonant. But that’s not the point. The curious thing is that Wallpaper’s tears – two discreet droplets trickling down his cheeks – became instantly contentious.

Why? A man weeps at a funeral. He doesn’t howl; he doesn’t roll on the floor, ululating as he drees his weird. If you can’t weep at a funeral, even a funeral of such pomp and vainglory as this one, when can you weep?

And tears speak for themselves. I am a lachrymose man myself. I have wept while talking about King Lear to students. I weep with a peculiar joy at Randy Newman singing “Same Girl”, at Brünnhilde sending the ravens home as she enters the funeral pyre. I weep at the Trisagion in the Good Friday Mass when the Greek and Latin words speak across the choir and across the millennia. I weep at musicals, at the death of Little Jo (but not of Little Nell). I once wept, proleptically, over my dog when he was young: there he was, his head in my lap, and I was stroking him and imagining that one day I would take him to the vet for his quietus and as the kindly needle went in, I would recall that, once when he was young, he lay with his head in my lap as I stroked him, and weep ... and so I wept at the thought of myself, years to come, weeping.

If I had to account for my tears – any of my tears – I'd be hard pressed, and embarrassed, and so would you. We are a lachrymose species. We appear, at least, to be the only lachrymose species. Why we should weep is a mystery, though we know that our tears contain stress hormones and indeed prolactin, the hormone which lets down the milk in nursing mothers and triggers the post-coital afterglow.

Tears are embedded in our culture. And not only ours. Omar Khayyam reminds us all our tears cannot “wash out one Word” of our past. Two millennia and more ago, Virgil wrote sunt lacrimae rerum, “there are tears of things”. Shakespeare’s Richard II wept at the loss of his crown; his Hamlet denounced his mother, “Like Niobe, all tears” at his father’s death then within days marrying his uncle. A goddess may weep for her mortal beloved (Artemis for Hippolytus), a mother for her child (the Stabat Mater), a father for his son: “And the king was much moved, and went up to the chamber over the gate, and wept: and as he went, thus he said, O my son Absalom, my son, my son Absalom! would God I had died for thee, O Absalom, my son, my son!”

Even (in allegedly the shortest verse in the Bible) Jesus wept.

And there’s part of the explanation, and part of the problem.

Jesus wept because his friend Lazarus was dead; he had arrived too late to say goodbye; he was surrounded by others weeping; and he was, as a mere man, powerless. (The story, of course, goes on to contrast his human powerlessness with his sacred authority.) We weep when we lose power, autonomy, control, when we are overwhelmed. And those are the last things we want to see in a leader, in one who’s responsible for our destinies.

Even in the ancient world, weeping, in a statesman, was suspect. Look how the chronicler of Roman emperors, Suetonius, treats Nero, who wept and fussed and wept again over his suicide in the face of insurrection. “Qualis artifex pereo,” Suetonius has him say. “What an artist dies with me!” Compare that with Otho, who kills himself under similar circumstances. He makes sure everyone’s OK, gets a night’s sleep and when he wakes up, efficiently stabs himself in the heart. Suetonius approves: that is how an emperor should behave.

The worst thing is dissembling. We simultaneously distrust and are fascinated by actors because they can fake it. They can fool our highly developed detection systems. And now that politicians have become media folk, celebs, actors, they are subject to the same rule. Our only defence is: are their tears worthy? Is there sufficient cause?

And this is where Wallpaper fell down. We could understand the tear in the Queen’s eye at Aberfan; by years of self-control, she had earned the right to weep. Wallpaper Osborne hasn’t, nor can we understand why he wept at Lady Thatcher’s funeral. So we assume that it was about him.

Well of course it was. Weeping always is. It’s about purging ourselves, not about helping others. The weeper is always at the centre of his own stage and we suspect him, perhaps, of – knowingly or unknowingly – wanting to upstage the others.

We might agree with Spinoza, who wrote “Do not weep. Understand.”

Or we might simply fall back on Hamlet’s question: “What’s Hecuba to him, or he to Hecuba/That he should weep for her?”

We’d be wisest of all, of course, just to say “George Osborne shed a tear at a funeral” and acknowledge it’s none of our business. But that would be too much to ask. This is, after all, politics.

Michael Bywater’s books include ‘Big Babies: Or: Why Can’t We Just Grow Up?’, published by Granta

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies