I never thought of myself as an outsider. Until now

It was only when I read a profile of that fire-breathing radical of the theatre, Steven Berkoff, that I began to understand

The two-week book festival is under way in Edinburgh.

Every day, a leafy square in the city is full of marquees, with authors reading, discussing their creative processes and answering questions from eager, bookish audiences. I am not one of those authors this year but, since I have a show on the Fringe for the month – narrated by a lonely and seriously blocked author, coincidentally – I sometimes hang around the square, attending the odd event.

It feels rather as if a new literary crowd is in town, and that my face doesn’t quite fit any more, an impression confirmed when two students handing out flyers for my show outside the square were told to move on by book festival bouncers. At one point, I met a writer friend, someone I had not seen for a while, at a signing session in the bookshop. He later tweeted that had been “pounced up by a heavily disguised and uninvited @TerenceBlacker”.

It seemed a little harsh. The heavy disguise was a hat and I had only been saying hello, but his remark confirmed the odd sensation I had of becoming an outsider. It is not something I have experienced since first trying to make my way as a writer in a literary world that was (and still is) inward-looking and occasionally snobbish.

I mentioned my experience online to the great crime writer Val McDermid. “I always felt like an outsider,” she replied.

Now this is odd. One would think that no one could feel more secure, more on the inside of things, than this deservedly popular Scottish author at the Edinburgh Book Festival.

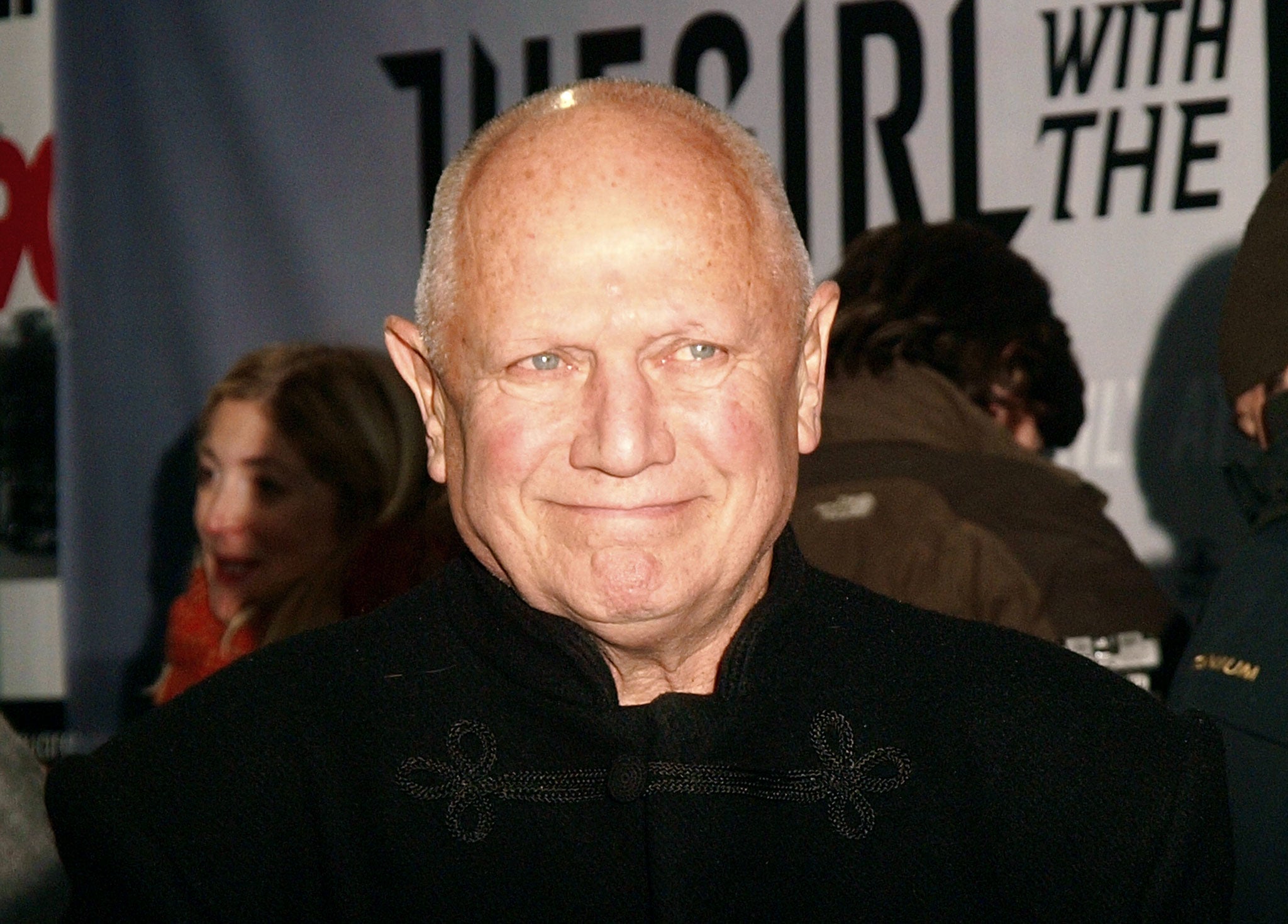

It was only when I read a profile of that fire-breathing radical of the theatre, Steven Berkoff, that I began to understand. The actor, writer and director is drawing on experiences from a glorious career for a show on the Fringe called An Actor’s Lament. Every day he is happily shouting and strutting his way about the stage before sell-out audiences. Yet it turns out that he is an outsider, too. He relishes the role, he told a journalist in a profile this week. “It’s almost a privilege,” he said. “It means you don’t speak in the same tongue as the mass. The outsider really is the insider because he is one who penetrates to the core.”

It is certainly a long way from the outsider, as portrayed by the writer Colin Wilson in 1956 when he was living rough on Hampstead Heath and working on his book in the British Library. A huge bestseller, freighted with portentous musings about Hesse, Dostoevsky and Sartre, Wilson’s The Outsider caught on because both the book and its author spoke to bookish, frustrated young men who thought the world misunderstood them.

Unfortunately, Wilson became over-excited by all this, rattled out too many books, mostly about sex, and at one point outed himself as a panty-fetishist – a boast which, even for an outsider, was considered to be over-sharing.

Being on the outside is different today. Steven Berkoff very obviously loves causing a fuss by being rude about Twitter, the BBC or the establishment. Promoting his play, he said during a radio interview that most of what the BBC produced was “garbage”. He was also firmly against “the general corruption that is going on”.

There was, gratifyingly, a row. Berkoff received more than 1,000 emails. Every singe one, he revealed in his interview, had agreed with him and had congratulated him on his courage.

Here is a perfect example of the 21st-century outsider. No sleeping in ditches or panty-fetishism for him. Instead, he pronounces at maximum volume a few bold, populist generalisations.

There is altogether too much communication, says Steven Berkoff. “It is like exposing yourself on a continuous basis. It’s like flashing.”

Who could possibly disagree with that?

Terence Blacker’s ‘My Village and Other Aliens’ is on daily at 5.30pm at the Zoo Southside on the Edinburgh Fringe until 26 August

Is it a cry for help, Jeremy?

Even at this time of the year, one can learn something new and interesting from the headline stories. Who knew, for example, that men liked to grow beards on their holidays, sometimes prolonging that holiday feeling by not shaving for days, or even weeks, after they return to work?

The breaking news about Jeremy Paxman’s facial hair is not only a perfect August story, combining themes of celebrity, looks, ageing and the BBC, but also raises the important question as to why men grow these things in the first place.

One psychologist has linked beardiness to dominance and aggression, but logic would surely suggest the opposite. A man’s need for a big, hairy face is more likely to be caused by a fear that his powers are on the wane. The bearded man is trying to make himself look bigger and more imposing than he is.

What Paxman has done to his face may be less a holiday folly than a cry for help.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies