Inside Whitehall: Speaking truth to power can be a little risky for your political health

Ministers believe that the civil service has been slow to face up to its problems

Just like retired generals, former civil service mandarins play an odd and unique role in public life. Because their successors are unable to speak freely and openly about what they think of their political masters, that job is left to the recently departed.

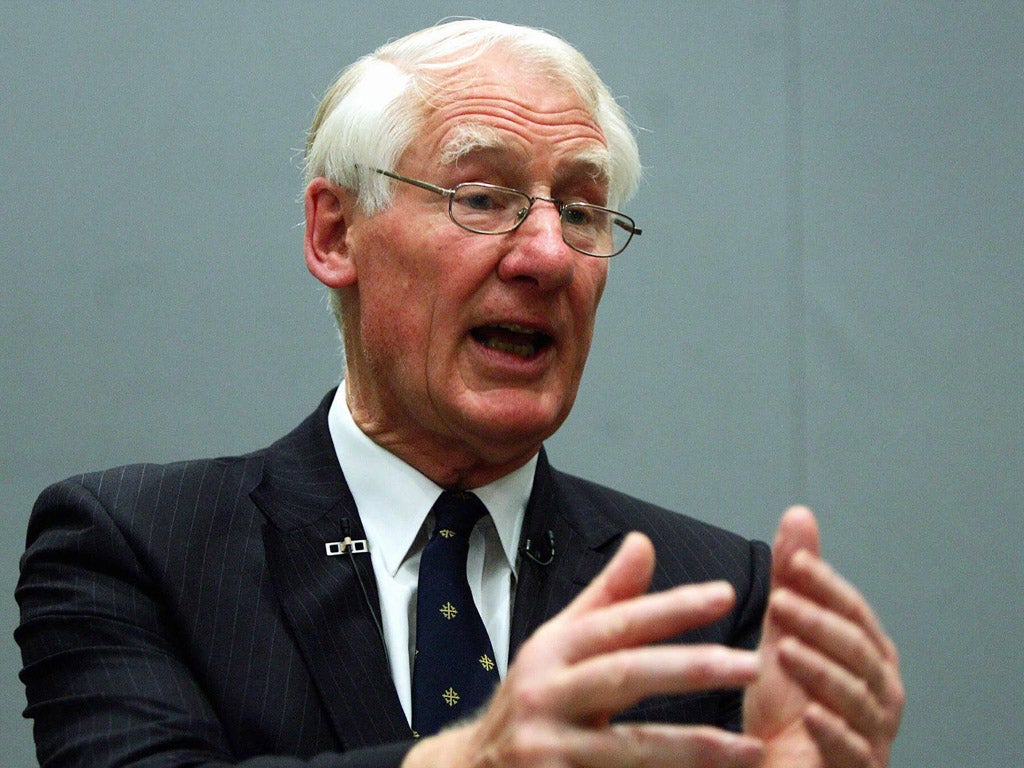

So when ex-generals complain in the Daily Telegraph about plans to reduce the size of the army, it’s a fair bet that what they’re really doing is making the case in public that their successors are making behind closed doors. And when Lord Butler, formally Cabinet Secretary under Margaret Thatcher, John Major and Tony Blair, starts attacking politicians in public, he is similarly not just speaking for himself.

In a recent interview with the BBC, he accused ministers of unfairly “dumping on” the civil service. Referring to recent comments by the Cabinet Office Minister Francis Maude that civil servants should “speak truth to power” more often, Lord Butler retorted: “People are not encouraged to speak truth to power when in the same breath in the same interview they are told that they will be dumped on when things go wrong.” He continued: “I’m sorry to say, I really think that Mr Maude and some of his colleagues don’t understand leadership. Backstairs sniping, whichever side it comes from, shows that something is wrong.”

It would be fair to say that Lord Butler’s views do represent, to a greater or lesser extent, private misgivings held by some of Britain’s most senior civil servants. Most were appalled at the private political briefings against Robert Devereux, the permanent secretary at the Department of Work and Pensions, over the failures of the Universal Credit programme.

They felt Mr Devereux was being unfairly blamed for predictable failures in an overly ambitious, politically driven scheme to which they could never have objected. “Iain Duncan Smith would clearly have taken the credit if things went well,” said one Whitehall source. “So it is a bit unfair to pass the buck when there are problems.”

Others, such as the head of the Civil Service, Sir Bob Kerslake, feel their positions have been unfairly undermined by anonymous but authoritative suggestions that they no longer have the confidence of the Prime Minister.

Sir Bob and others are well aware that at least two permanent secretaries have quietly been shuffled out since 2010 because of disagreements with their political masters. How can you speak truth to power, they ask, when if power doesn’t get the right answer it gets rid of you?

And there are wider disagreements as well. Collectively, permanent secretaries feel that elements within the Coalition (led by Mr Maude) are embarking upon a confrontational approach to reforming the civil service that has the potential to undermine Whitehall’s political neutrality and do significant damage to the institution for which they work and care about.

On the other side, ministers believe that the civil service in general has been too slow to face up to its institutional problems: that it is not good enough at major project delivery, that poor performance is too often tolerated and that a risk adverse culture is holding back good public services.

So beyond the leaks and the hand wringing, what’s to be done?

Yesterday the independent Whitehall think-tank the Institute for Government produced a detailed “manifesto” for civil service reform that would do much to address the concerns of ministers and mandarins alike. For the politicians, it recommends a proper system of accountability for senior civil servants.

No longer would permanent secretaries be set vague and immeasurable performance objectives that can easily be fudged and reinterpreted. Instead they would commit to a short list of published implementation priorities – agreed with their secretary of state – as well as a set of longer-term and ongoing objectives.

Civil service leaders would then be appraised against these objectives, with input from the National Audit Office, which monitors departmental performance. There would thus be a mechanism to remove a poor performing permanent secretaries – but harder for political motives alone. The IfG’s recommendations also include other important safeguards for the civil service. It calls for a significant extension and routine use of “ministerial directions”, a mechanism by which a permanent secretary can request a letter of direction from their minister to proceed if they have doubts about the value for money or feasibility of a particular use of public money.

Together, the proposed reforms would do much to address the underlying tensions and might mean today’s senior civil servants no longer need play an ex-officio role in public life.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies