Our PM is too posh to push for the Union with Scotland – and knows it

David Cameron may agree that Scotland's No campaign doesn't need help from a Tory toff. But what exactly is this quality that arouses such strong reactions?

By chance, one of last week's most significant political stories came bearing an equally significant sociological garnish. The political story was the Prime Minister's reluctance to campaign against Scottish independence, and the sociological top-dressing could be found in the reason he gave for not debating the issue with the SNP leader Alex Salmond.

Responding to a claim made by Ian Davidson, the Labour MP for Glasgow South West, that "the last thing Scots who support the No campaign want to have as their representative is a Tory toff from the Home Counties", Mr Cameron seems more or less to have agreed. At any rate he would only remark that while he was sure many people in Scotland would like to hear his views, "my appeal doesn't stretch to every single part". No doubt about it, from the angle of Clackmannanshire and Wester Ross, Mr Cameron, as the newspapers were quick to confirm, is just too posh.

All this, naturally, raises fascinating questions about how the Prime Minister perceives himself, how we, in our turn, perceive him, and, most important of all, the precise meaning of the word that so often accompanies mention of his name. There is a personal interest, too, in that "posh" was one of the great all-purpose adjectives of my childhood, sometimes used to convey approbation, as in "that's a posh suit/car/pair of gloves", but more often used in bitter disparagement, when it meant "affected", "pretentious" or "lah-di-dah". Its most regular application was in the field of vocal tone, and my father did a ruthlessly accurate impersonation of some "posh" people he had once sat behind at a classical concert, a phonetic reproduction of which would go something like: dahs wan hev wan's years pierced?

I was not immune to these reproaches myself, and got a terrific ticking off for returning from my first term at university with what was described as "a half-crown voice". But to go back to David Cameron, who is unequivocally posh, indisputably the poshest Prime Minister since Sir Alec Douglas-Home 50 years ago, of what does his poshness, his quite incontestable air of poise, superiority and upper-class sangfroid, consist? One should note immediately that "posh", like most other adjectives tethered to the idea of social class, is a relative term. Victoria Beckham, for example, was dubbed "Posh Spice" by the tabloids because her parents possessed a freehold property. Obviously blue blood has its place, and one of the most amusing stories I've heard about the Prime Minister was the degree of social exaltation he was supposed to have displayed on his engagement to Samantha Sheffield. She is a baronet's daughter, you see, and in certain circles this still counts for something.

Money, it scarcely needs saying, has nothing – or almost nothing – to do with it. The earl's granddaughter who survives in a dower house with the family money all gone, the estate sold and the flower-garden dug up for potatoes is a novelist's staple, and no survey of British demographic history over the past century and a half can quite ignore that tiny but influential cadre known as the aristocratic poor. Accent is nearly always a reputable guide, its taint discerned in the desperate attempts made by well-bred Labour MPs to sound as if they had managed to avoid a privileged upbringing. The former foreign secretary Anthony Crosland (Highgate School and Trinity College, Oxford) is supposed to have lamented to one of his advisers, on returning from a radio interview, that he "wished he didn't sound like that" and when asked what he thought he sounded like, replied – my father's term again – "so lah-di-dah".

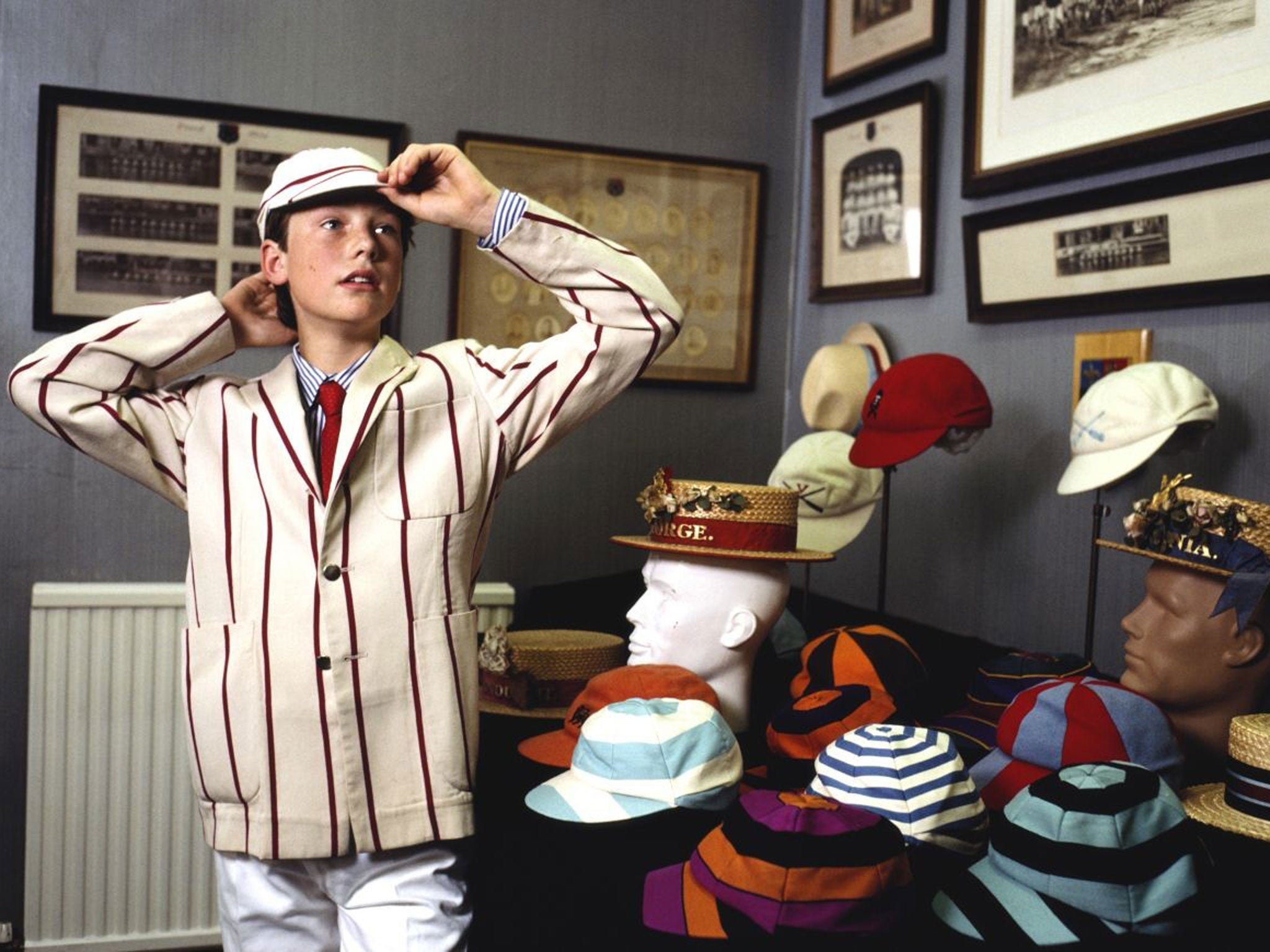

Education, of course, is an important key to "poshness", and yet, once again, enormous distinctions and qualifications apply. You might assume that attendance at one of our leading public schools was a guarantee of it, but any counter-jumper with a few thousand in the bank can buy a GCSE and so a near-invisible fence rail operates to keep the sheep from the goats.

Eton is a posh school; Harrow, I was always told by non-Harrovians, is not. At university, 30 years ago, the boys from Dulwich College were looked down on as south London barbarians and pursued around the place by imitations of their supposedly cockney argot.

The amateur sociologist, noting that money and education are no guarantee of poshness, and that even an up-market tone can be acquired by way of elocution lessons, might wonder exactly what factors are left. The answer, predictably enough, has to do with intangibles, spiritual caste marks that linger in the air like river fog above the heads of the people who benefit from them. It is not that the posh have fruity, patrician voices, that they went to Eton, are descended from King William IV or are married to Sir Reginald Sheffield's daughter, rather that they are susceptible to tiny twitches on the ancestral thread, barely calculable behavioural assumptions, that eternal question of "how to behave" to which posh antennae are always finely tuned.

One infallible mark of poshness, for example, is the habit of pronouncing one's name with cavalier disregard of its spelling: Powell as "Pole", Seymour as "Seymer", Featherstonehaugh as "Fanshaw". Another is to pronounce fairly ordinary words with peculiar emphasis, like the owner of the flat I once inhabited in Pimlico who informed me that "Fletcher" might call, that is the well-known firm of letting agents "Flatshare". And all this is to ignore the whole Mitford-esque pantomime of swapping "serviette" for "napkin" and the sumptuary prescriptions of the late Earl Beauchamp who decanted his champagne into jugs on the grounds that drinking it from the bottle was middle class.

And at the heart of poshness, my fascinated observation of it insists, lies not birth, breeding and cut-glass vowels, but a much more subtle and demanding requirement: the ability not to show off, draw attention to oneself or appear to require more than the most minimal appreciation of one's talent, a kind of chronic reserve and self-deprecation whose exercise, if taken to extremes, can sometimes look like showing off by default. I was once taking part in a conversazione about the novels of Anthony Powell with the novelist Ferdinand Mount, who is the Prime Minister's cousin. At one stage I ventured what seemed an unexceptionable point about the way in which Powell's characters "declare" themselves, slough off one skin, as it were, and acquire another. "I say" Ferdie tolerantly remarked, "that's awfully clever." It was no good. I had shown off, I was not fit for polite company, and – metaphorically – I slunk away.

On the other hand, there is virtue in all this poshness as well as vice. In fact, all the evidence suggests that the Prime Minister should stop regretting his poshness and use it as a weapon. After all, the patrician values he appears to espouse seem to make him more popular with the electorate – the English electorate, anyway – than upstart proletarians such as Eric Pickles or the middle-class Darwinians who populate the Cabinet's lower reaches. And, what with Pop (Eton Society) and the Oxford Union behind them, posh boys invariably make a decent showing in the debating chamber. In declining to spar with Alex Salmond, Mr Cameron may be missing a trick.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies