Rosetta space mission: Not even the sky is the limit for what European cooperation can achieve

No other mission has had Rosetta’s potential to look back to the infant Solar System

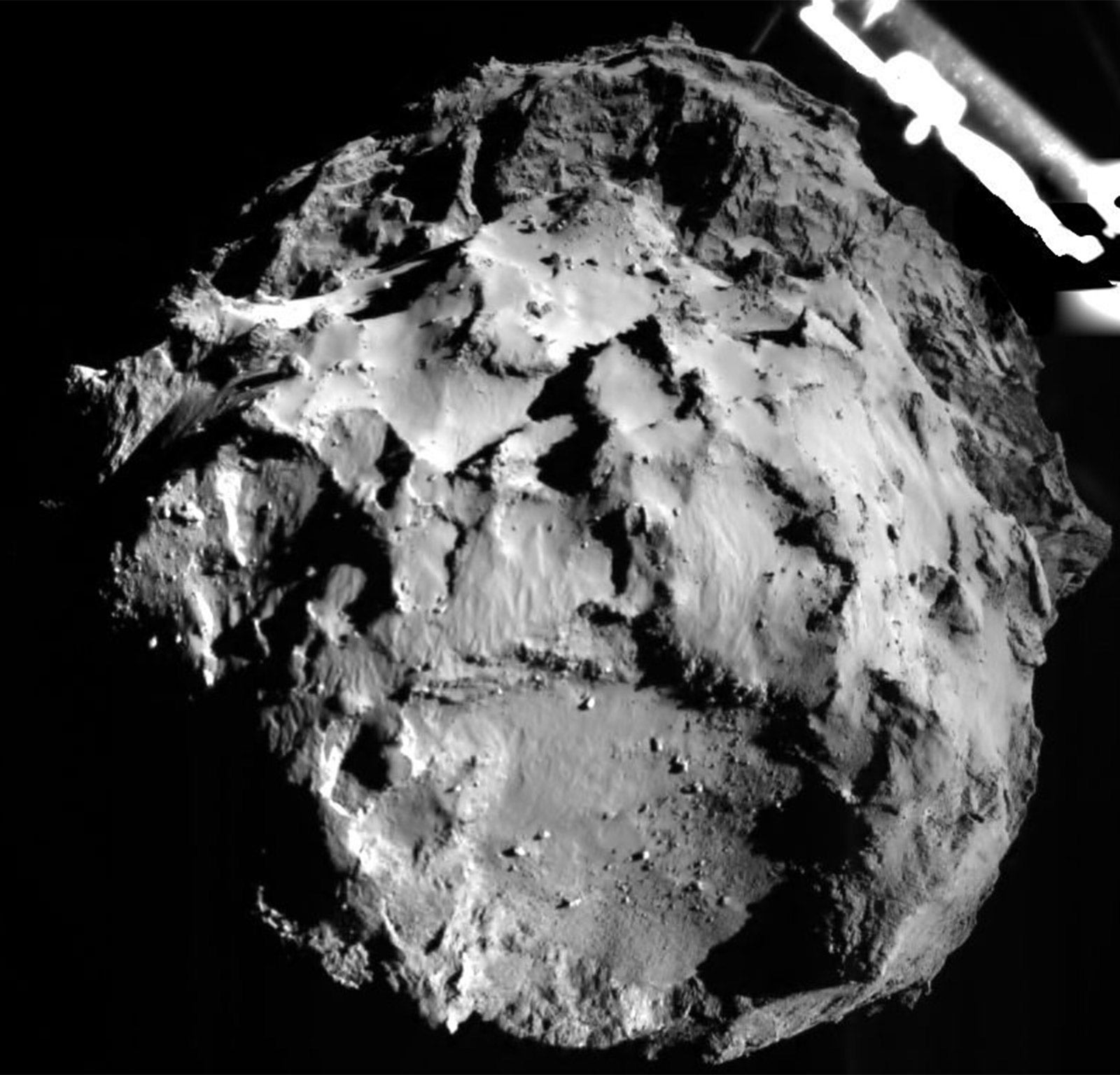

Landing a spacecraft on a comet is not as complicated as you think: it’s several thousand times more so. After an initial ten years of research and preparations the European Space Agency launched the Rosetta satellite in 2004. It has taken this unmanned craft a further ten years, and 4 billion miles, to reach its current position, from which it was able yesterday to detach a lander, a little fellow the size of a fridge going by the name of Philae, and send it to harpoon itself on an irregularly-shaped, 2.5 mile-long rock travelling at a speed of 40,000mph.

Why are they doing this? The comet’s composition reflects that of the pre-solar nebula out of which the Sun and the Solar System formed. Analysing the comet will reveal some of its secrets. Even if the landing had failed, which was a real possibility up until the last moment, no other mission has had Rosetta’s potential to look back to the infant Solar System.

The European Space Agency is a perfect illustration of the value of European co-operation. Its budget, which was €4.28bn in 2013 is paid for in large part by the EU and its member states – 21.3% (€911.1m) of its budget came from the EU in 2013, and the lion’s share of the rest came directly from EU member states, with smaller contributions coming from Canada, Switzerland, Norway, and ESA candidate states. The budget for the Rosetta project was €1.4bn.

Not only is the money shared but so too the work – the ESA has centres all around the continent serving different purposes: astronauts are trained in Cologne; Mission Control is in Darmstadt; Research and Technology is based in Noordwijk; Earth Observations in Frascati, and Space Astronomy in Villanueva de la Cañada. All of these collective resources combine to create a co-operative organisation which is forward-looking, ambitious, and fundamentally European.

Researchers from Open University’s Centre for Physical and Environmental Sciences worked with the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in Oxfordshire to develop Ptolemy, an instrument which will make in situ isotopic measurements, since you ask – one of the many tools the Philae lander will use to analyse the comet. And OU researchers also had a hand in the development of MUPUS (Multi-Purpose Sensors for Surface and Subsurface Science) which was led by a consortium of European scientists from Münster, Berlin, Warsaw, and Graz.

None of the nations involved could have hoped to achieve this goal single-handedly. None would even have attempted it. None of the multi-lingual experts who came together would ever had a chance to be part of something this complex, enriching, fascinating and, yes, just plain exciting, without the European Space Agency. It is through the ESA that the UK Space agency gets a place at the table, or on the spacecraft, through the instruments developed by UK scientists, funded by taxpayers in Bristol, Boulogne and Berlin.

It’s cost us ten years, millions of pounds and man-hours but the result of this feat of European co-operation, fundraising, co-ordination and joint research is truly priceless.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies