Save lives Mr Cameron, but don’t imagine you need to save Africa

Why does Cameron think Africa is in need of redemption?

This week, the Prime Minister went to Africa.

Struggling to achieve anything at home thanks to the shaky state of her coalition, she decided to boost poor poll ratings by becoming a peacemaker on the continent, flying off to join the swollen ranks of self-interested saviours who use it as an exotic backdrop for their own ends.

I am, of course, referring to Birgitte Nyborg, fictional leader of Denmark and Europe’s most popular politician. Unfortunately, Borgen – a rare programme showing politics as a complex and consensual process – went spectacularly wrong when it headed south. Africa was painted in the most clichéd colours, with war, homophobia and machete-wielding citizens – to say nothing of the one-dimensional characters.

So much for the stereotypes. In the real world, despite recent events in Mali, conflict is becoming rarer on the continent. Meanwhile, economic growth is soaring, poverty declining and infant mortality plummeting at unprecedented rates. As on other continents, profound problems remain ingrained – but Borgen vividly demonstrated the outdated prism through which many Westerners still see Africa.

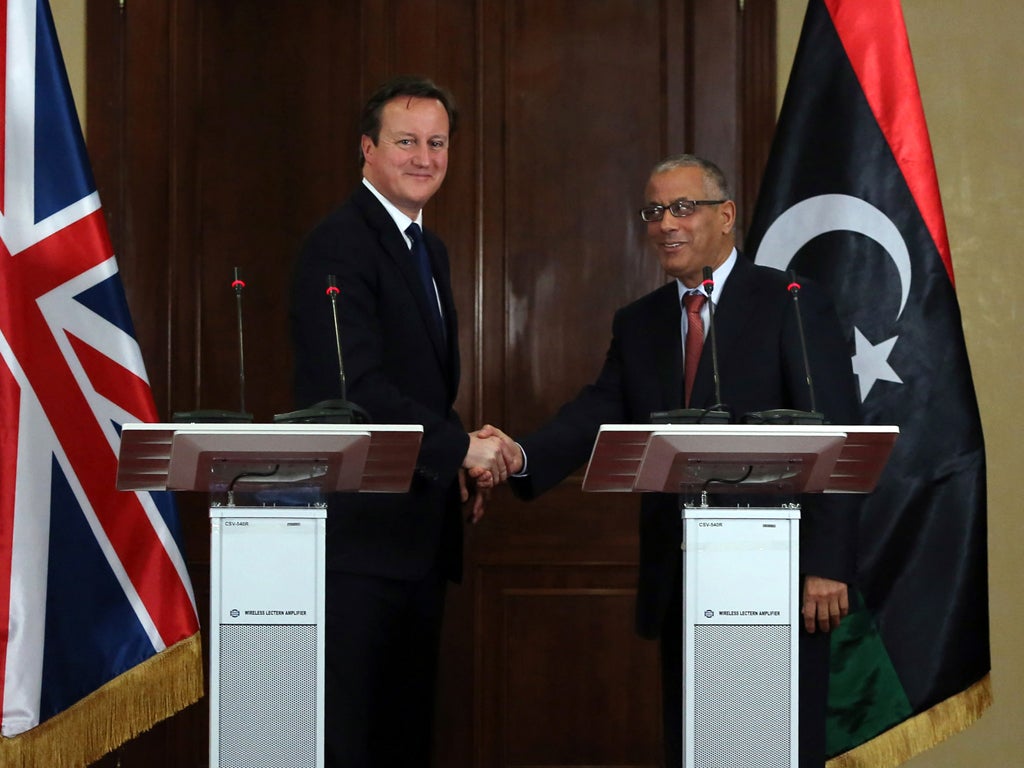

Life imitates art, for our own Prime Minister made that trip this week. In Algeria, he was building new alliances as part of a supposed “generational battle” against Islamic militancy. In Libya, he underlined the struggle to rebuild a state run by a dictator for 42 years. And in Liberia, he chaired a panel on the next UN millennium development goals.

Taken together, they demonstrate the Cameron doctrine on foreign policy: a belief that Britain should be a force for good in the world whether using aid or the armed forces. Many at Westminster have been taken aback by his liberal interventionism, although it reflects his approach since becoming leader of the Conservatives. In opposition, he flew to Tbilisi to stand alongside a Georgian democracy threatened by Russian aggression; in government, he rushed to Tahrir Square to embrace the Arab Spring.

Among his most formative influences was travelling as a student in Eastern Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall, feeling the palpable excitement at the downfall of despotism. Like some of his closest advisers, he was influenced also by the lamentable failure of a Conservative government to intervene in the bloodstained break-up of Yugoslavia; he saw that doing nothing could be as fateful a choice as doing something.

This is why he stepped in to save Benghazi when it was threatened by Gaddafi’s fightback against the revolt of his people. It was a courageous action that paid off, for all the bumps on the road to rebuilding stability that will inevitably occur after four decades of dictatorship. And it is why he was so quick to support France after its admirable decision to protect Mali from falling into the hands of Islamic zealots.

It is, however, one thing to stop atrocities and protect human rights. It is another to fall for the delusions that disfigured the premiership of Tony Blair: the arrogant, misguided and dangerous idea that the West can impose its vision on the rest of the world. Blair began with a successful, limited intervention in Sierra Leone, which encouraged him to end up eventually trapped in the morass of his own making in Iraq. Then there is the weeping sore of Afghanistan, a tragic indictment of Western attempts at state-building.

As Britain prepares for its latest retreat from Afghanistan, we can see the limits to our ability to reshape the world in our desired image. It also shows how intervention can backfire so disastrously; look at Pakistan, into which we are pouring vast sums of aid in an effort to repair collateral damage from our disastrous invasion of its neighbour.

Cameron’s statements on foreign affairs can sound like uncomfortable Blairite echoes, fuelled by salvation fantasies. True, the Prime Minister was privately sceptical over the Iraq misadventure, has said he is not a “naive neo-conservative” and dismissed the concept of “dropping democracy from 40,000ft”. He must not forget this as he discovers new challenges in Africa. Ultimately, it will be Malians who find their own solutions to the long-festering and complex problems that exploded so dramatically over the past 10 months. Yet just as the West must be wary of extended interventions backfiring across the Sahel as they have done so disastrously elsewhere, so we must learn our own lessons from recent events in the region.

After all, Mali was a “model democracy”; we need to understand that democracy goes far deeper than just the occasional ballot, a lesson of importance elsewhere in Africa. And it had an ineffective, corrupt government propped up by the West’s anachronistic aid policies. The nation’s plight is another testament to the failure of these simplistic and flawed ideas, even amid a boom in charities claiming expertise in building states.

Aid and the armed forces have a role to play in a crisis, but they are not weapons to rebuild a nation in the longer term. If Western leaders really want to help Africa, they should forget grandstanding gesture politics and tackle issues closer to home. After all, whose protectionist policies squeeze African traders and farmers? And where are those banks, property advisers and lawyers that launder all that stolen money?

This week, two prime ministers visited Africa, the continent which will itself define this century for better or for worse. We must hope the real life one returns with a more modern view of its people than his fictional counterpart.

Twitter: @ianbirrell

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies