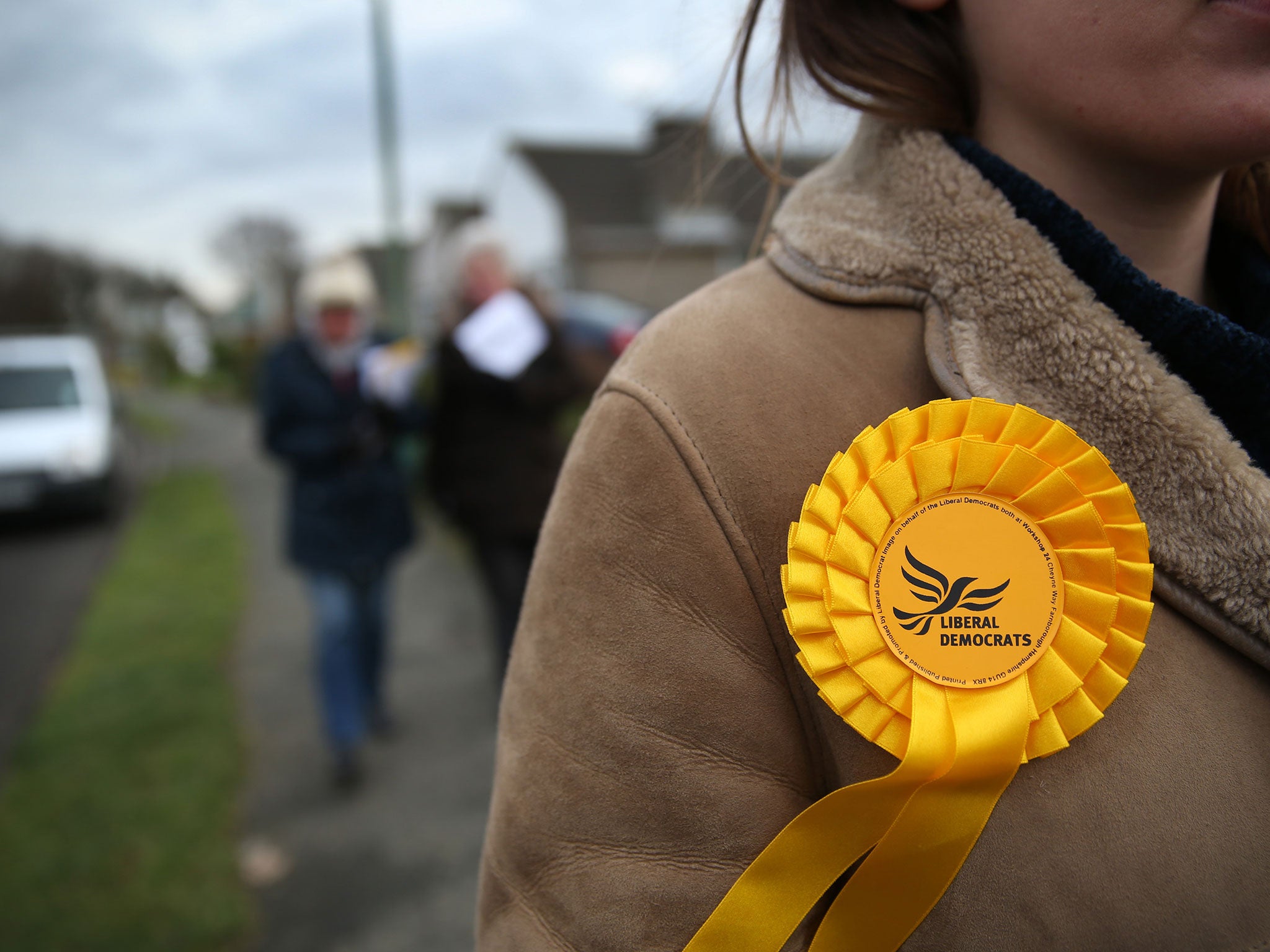

The crushed Lib Dems are mired in an identity crisis - can they fix it?

The journey from the wilderness may take a generation – and won’t happen at all if the party can’t agree a destination, says former special adviser Julian Astle

The danger, when heavily defeated political parties ask themselves why they collapsed and how they will recover, is that the interrogation is too superficial, the questioning too narrow.

For the Liberal Democrats, who in the past five years have lost 49 of their 57 MPs, 10 of their 11 MEPs, 11 of their 16 MSPs, more than half their 4,000 councillors and two thirds of their 6.8 million voters, that danger is clear and present.

The current mood at party headquarters is one of defiance as a post-poll membership bounce is held up in an endless stream of tweets as proof of a #libdemfightback. But the party’s most experienced heads realise the journey back from the political wilderness could take a generation to complete, and won’t be completed at all if, in the coming weeks and months, a plausible destination and a viable route are not identified and agreed. There is no point rushing off if you don’t know where you are heading.

The conversation that is now needed should begin with the most fundamental question of all: if the Liberal Democrats did not exist, why would it be necessary to invent them?

We live in an age of plural politics. Not so long ago, there were only two other parties for the Liberal Democrats to worry about. Today there are six, all of whom are more clearly defined than the Lib Dems.

The Conservatives are the party of wealth creation; Labour of social justice; Ukip of EU exit and immigration control; the Greens of left-wing environmentalism; the SNP and Plaid Cymru of Scottish and Welsh independence.

In a crowded marketplace, definition matters. The ability to describe who you are in a single word or sentence is an increasingly precious commodity. It is one the Lib Dems do not currently possess.

The proximate cause of the Liberal Democrats’ identity crisis was the decision to fight the election as centrists rather than liberals – a decision that the party leadership knew, deep down, risked leaving them with a functional and lifeless message, devoid of the sense of moral purpose and historic mission that made Clegg’s resignation speech his best of the campaign.

But as so often, the “science” of the party’s internal polling won out – in internal discussions, numbers beat opinions. Discovering that many potential Liberal Democrat voters thought the Tories too right wing and Labour too left wing, it was decided that the Lib Dems would present themselves as the “anchor” that would stop either party from drifting too far from the political centre. In so far as this gave the party a reason to exist, it was to moderate the worst excesses of whichever party it might end up working with in government – a dismal offering. Not only did this tell voters nothing about the party’s own vision for the country, it actively undermined its claims to have one. If the Tories want to travel 10 miles to the right, and Labour 10 miles to the left, the logic of the Lib Dem position was that they were prepared to travel in either direction, but only for five miles.

What is more, that message didn’t even serve its intended tactical purpose in the 2015 election. It is a matter of simple human psychology that people who hate or fear the Tories or Labour don’t want a party that will moderate them in government. They want a party that will keep them out of government. The Lib Dems were unable to provide that assurance in either their Conservative-facing, or their Labour-facing, seats.

If the proximate cause of the Lib Dem identity crisis was the triangulation between Labour and the Conservatives that left the party without a positive message of its own, the underlying cause – and the one the party leadership candidates will try hard not to discuss in the coming weeks – is the unresolved battle between the party’s Right-leaning economic liberals and the Left-leaning social liberals about the true meaning of liberalism.

It is an uncomfortable fact, but a fact nonetheless, that liberalism straddles the Left/Right fault line that runs through our politics. When that fault line opens – as it did when the 2010 election produced an inconclusive result – a Liberal has only three options: jump left, jump right, or disappear into the void. Clegg and his colleagues did what they believed the electorate wanted and the national interest demanded, and jumped right. Half his voters jumped left.

The question that has paralysed the party ever since is whether to remain where they are or to head back to the territory occupied by Paddy Ashdown, Charles Kennedy and Ming Campbell.

To the majority of Lib Dems, this is a “no brainer”. The party grew throughout its 20 years on the centre Left. Since moving to the Right, it has collapsed.

Unfortunately, not only has the anti-austerity Left since become the most crowded part of the political landscape, but the bridge that leads back there may well be broken. A party that has spent five years attacking the deficit with the Conservatives cannot credibly spend the next five denouncing “Tory cuts”.

What it can do, however, is tap into the innate liberalism of the British people which social attitude surveys show is growing stronger with each successive generation.

Last week, the front page of this newspaper announced the “strange death of liberal Britain”. But look at the views of the generation born after 1979 and it is impossible not to see a future for British liberalism and, if they can divest themselves of some of their favourite prejudices, for the Liberal Democrats too.

For rather than identifying either with the Left or the Right as the pre- and post- war generations did, and do, today’s young combine the social liberal views of the Left (secular, internationalist, concerned about the environment, relaxed about lifestyle choices and family structures) and the classical liberal views of the Right (in favour of balanced budgets, low taxation, conditional welfare, personal responsibility, individual choice and entrepreneurship) without seeing any contradiction between the two.

This increasingly educated, empowered, technologically savvy cohort is left cold by the conservatism of the Tory party and the collectivism of the Labour party. They are instinctive liberals. They just need a liberal party to vote for.

Julian Astle worked as a Liberal Democrat special adviser in 10 Downing Street from 2011 to 2015

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies