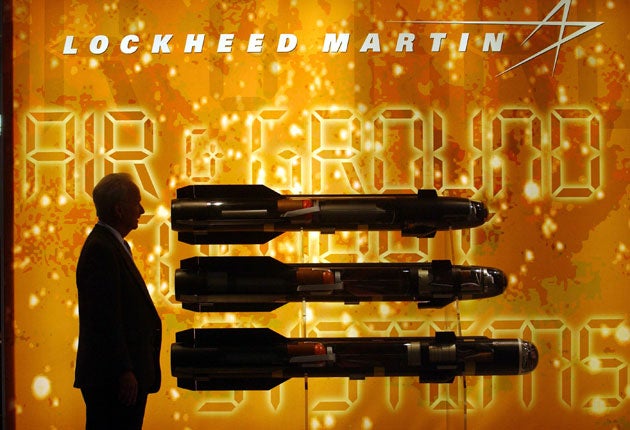

George Walden: Selling arms will always backfire on Britain

A former Tory minister says a rethinking of our attitude to the weapons trade might not be popular but is long overdue

"He was as much use to the Tory party as a cat-flap in a submarine" was one of the choicer comments on my decision to give up my Commons seat in 1997, and my views on the arms trade were, no doubt, one of the things that the wit in question had in mind.

Concerns that have surfaced after recent dramas about our policies on arms exports to unsavoury Middle Eastern countries are, for me, nothing new. Having worked in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office for 20 years before becoming an MP, I had grown conscious of the economic and political risks of our unhealthy dependency on this trade, let alone the ethical factor the Libyan carnage has forced on our attention.

Given the overall decline in our global share of manufactured goods, how did we get into the position of being one of the biggest arms exporters in the world, along with the US, Russia and France? It happened because after the Second World War, for all our poverty, we had an active international role and a large military establishment. Also, with advanced economies such as Germany and Japan out of the competition, we, together with the French, had a clear run for years. (In some sectors, the Germans have since caught up.)

It need hardly be said that an over-reliance on arms sales can oblige you to deal with the type of regime that is more concerned with having the latest in lethal gear than with the welfare of its people. Moreover, corruption in the trade is endemic. A senior Saudi figure accused of receiving kickbacks from the giant British al-Yamamah ("the dove") defence deals is said to have brushed off accusations of graft in his country with the words "So what?". As well as the recognition that graft was the cultural norm, the implication was "And what are you going to do about it?". The answer, of course, was, look the other way.

One of the most lamentable episodes in recent British history was the abandonment by Tony Blair's government of investigations into bribes allegedly paid by BAE, the prime contractor in the al-Yamamah deals, to Saudi individuals. (In 2005, BAE's chief executive said the company and its predecessor had earned £43bn from the deals over the past 20 years and could earn a further £20bn.) However, it had little choice. It wasn't simply a matter of protecting the interests and reputation of a major British company. The clinching argument was that the Saudis were warning us of reprisals, including in the security field. Proceed, and we might be less forthcoming about threats by jihadis to your country, was the message. In international affairs threats don't come starker than that.

The incident was a neat summation of the morass we are in over weapons exports. Yet hot flushes of indignation get us nowhere. A peacenik approach is self-gratifying but unserious. Pleas for the end of arms manufacturing and trading are immoral, because they wilfully evade the truth: that no morality can dispense with human realities. We live in a world in which physical aggression has always, and will always, exist. Weapons manufacture and sales will be necessary, domestically and between countries, so long as we need police officers on our streets.

If the moral aspect of the problem lay in grand dilemmas of conscience things would be simpler. Then you can have set-piece debates over situations such as the arms-for-Iraq affair. They resolve nothing and everyone feels better. But what really matters are the ethics of the everyday, which are not so easy.

A routine example: as principal private secretary to, first, David Owen and then Lord Carrington, I recall hesitating to approve without reference a submission to sell a consignment of lorries to Saddam Hussein. The problem was that, though civilian, and outside the scope of embargoes, they were capable of being converted to military use.

The factory in the north of England that made them was ailing, and jobs were under threat. If we didn't supply, I was assured that the French were eager to oblige and, unlike ourselves, would have no qualms about it. Hindsight aside, and remembering that ethics are not the sole preserve of politicians, what would you have done in the government's place?

Not that I buy the glib "arms sales equals jobs" excuse. On that basis, anything can be justified, brothels included. The arms trade itself is something of a global bordello: if you're worried about what Britain or the US get up to, take a closer look at countries such as China and Russia.

The problem for us is custom and habit. We have been at this a long time and, the larger the percentage of our skilled workforce involved in arms exports, the easier it becomes to dismiss doubts with a superior smile and that single word "jobs".

What troubles me is that no one seems to be confronting the strategic problem. There is never a good time for painful reassessments of national economic priorities, and whatever government was in power today would be unlikely to come up with one at the low point of a recession. On the contrary: with major cuts in the British armed forces, and a drive to increase manufactured exports and make us less reliant on the City, the search for foreign arms markets will presumably intensify, with the risk that even more ethical corners will be cut. That alone could explain David Cameron's apparently extraordinary decision to include defence salesmen among the businessmen accompanying him on his Middle Eastern tour.

Going on as we are is not an option. We rarely consider the opportunity costs – the chances missed as we look the wrong way. But while we invest so many skills and millions in making tanks and warplanes, we are being edged out of the market for more hi-tech civilian manufactures.

Advocating an urgent government review at this moment may be spitting in the wind, but that doesn't mean we should settle for doing nothing. There could scarcely be a better time for thoughtful economists, industrialists, defence experts and political thinkers to get together to examine the matter in depth, and to come up with a policy of diversification of national industrial effort over time. I am not talking idealistically about swords and ploughshares – though it would be sensible to have something other than swords to play with.

George Walden is a former diplomat, MP and minister. He retired from Parliament in 1997

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies