Mary Dejevsky: Could France show Europe how to move left?

World view

Across Europe, a widespread assumption has been that the combination of the cold economic climate, harsh austerity measures, and general disillusionment with politicians boosts the electoral chances of the populist right. The French presidential race, where Marine Le Pen offers a soft-ish version of the far-right option for the National Front, will be one of the first tests of this hypothesis.

It is possible, though, to conceive of another, quite different scenario that would have the effect of changing the political face of today's Europe almost as much. Instead of handing more power to the far right, Europe could take a decisive turn to the left. France, where the first round of the presidential election takes place on 22 April, will be the first test of this hypothesis, too.

At one level, what happened in Spain's elections late last year might seem to disprove this. Mariano Rajoy and his Popular Party won a sweeping victory for the centre-right. While it may be hard to disentangle voters' motives – were they primarily attracted by Rajoy's personality and policies or disappointed by the Socialists' exercise of power? – the likely explanation is the liability of incumbency. In the present harsh economic climate, no sitting government can consider itself safe. And it just so happens that many of those facing elections in the coming 18 months are governments of the centre-right.

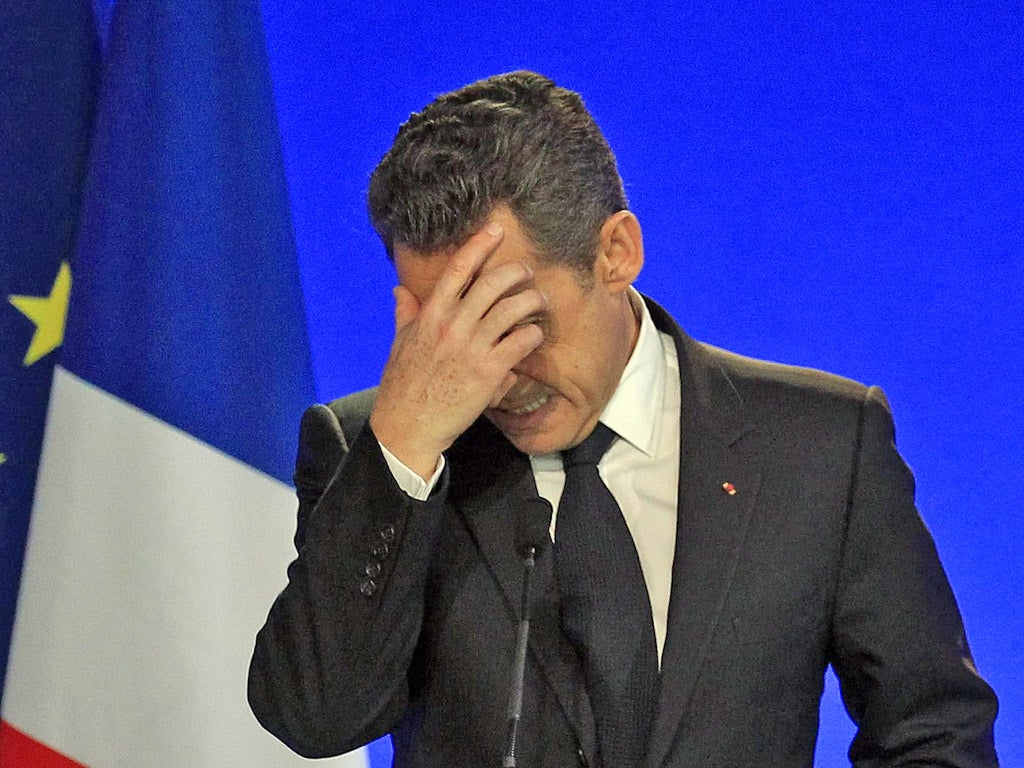

This includes France, where opinion polls show President Nicolas Sarkozy slipping behind his Socialist rival, François Hollande. And when Sarkozy says, as he did this week, that he will leave politics altogether if he is defeated, it is tempting to conclude that he has lost the stomach for the fight. Three months before the vote, there seems a real prospect of France electing a president of the left, even if it is not the one-time favoured Socialist, Dominique Strauss-Kahn.

Of course, these are early days. As Edouard Balladur and Jacques Chirac would doubtless agree after their experience in 1995, three months can be a very, very long time in French politics. And Sarkozy is a formidable campaigner with megatonnes of flair. If anyone can reverse hostile polls, it is he. Sarkozy may yet win a second term.

Let us suppose, though, that it is the face of François Hollande that French viewers see forming on their television screens at 8pm on election night. Let us further suppose that the same factors that brought him to power give him a National Assembly with a left-of-centre complexion a few weeks later. Let us then take the same line of thinking a little further and posit that elections which are due in Greece in the first half of the year and likely in Italy in the second half also turn up left-leaning governments or coalitions.

Then consider a further possibility: that by 2013, German voters are not only fed up with the continuing euro-crisis, but bored with two terms of Chancellor Merkel and frustrated with the ineptitude of her second coalition. If Germans then decide, as they well might, to give the Social Democrats another chance, the political face of Europe suddenly looks very different.

One view might be that, while the colours on the electoral map and the nameplates would have changed, actual policies would not. Such would be the constraints on any government, of any complexion – so this argument would run – that room for significant policy change would be negligible. There would be no more than a little leftward tweaking at the edges. All government would essentially be technocratic at home and led by realpolitik abroad.

But this is not necessarily what would happen. If left-of-centre governments were in power not just in France, but in Germany and Italy as well – in other words, in all three of the eurozone's largest economies – the effects could be far-reaching. It is striking that François Hollande's campaign speeches have a harder, more traditionally left-wing, edge than many European Socialist politicians have allowed themselves in recent years.

If not just one but several major EU countries turned to the left, one consequence might be a new, much more aggressive approach to regulation in many areas, but especially in the financial sector. Another might be a more egalitarian and redistributive approach to national taxation, and closer coordination of tax (and possibly benefits) across the eurozone. A third might be the burial of the 1990s preoccupation with economic competitiveness and greater attention to average living standards. A fourth might be the consolidation of a two-speed Europe, with moves towards political and fiscal union at the core, and a free-trade zone for everyone else. A fifth might be progress towards a common defence policy and EU armed forces – for economic, as much as political, reasons.

And a possible sixth consequence might be felt in Britain, where a major EU shift to the left could give Labour not only new faith in the feasibility of a credible alternative to the centre ground occupied by the Coalition, but new ideas about how to seize that ground for itself. With the Conservatives currently riding (relatively) high in the polls, that day might look very far off. The election of a Socialist President in France, however, could bring it – and a different sort of European Union – closer.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies