Greece debt crisis: What happened to democracy when it's a case of 'Vote Yes or else'?

If this 'democracy' doesn’t work in Europe, how is it supposed to work in India? Or the Middle East?

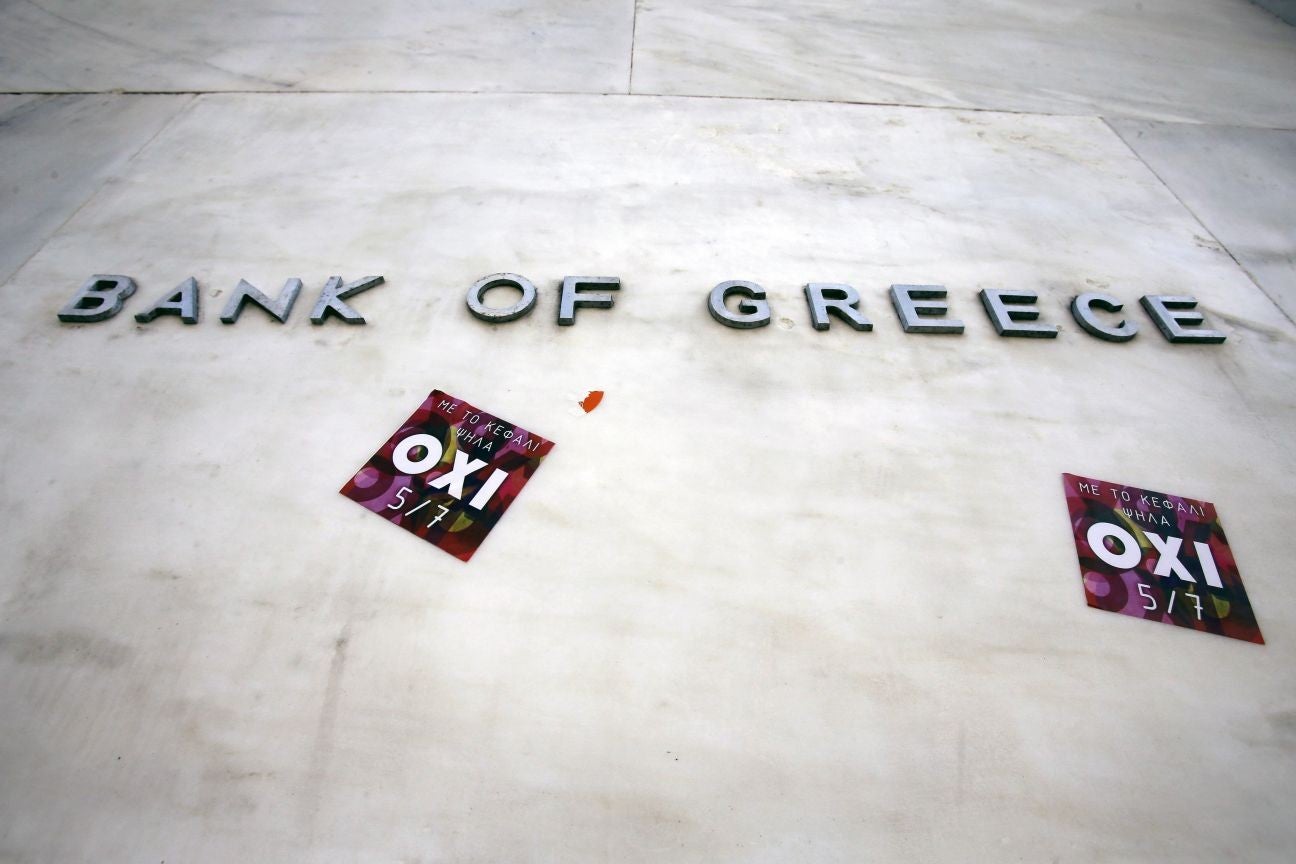

So the Greeks are going to vote Yes on Sunday. Fear. Humiliation. Patriotism (pro-European or pro-euro, we shall see). Or pragmatism, that great industrial powerhouse of European politics. And so the EU, the IMF, the ECB, the lot – they will have won. Greece – nil. Delete the Second World War.

The problem – and let’s forget for a moment how many millions the profligate Greeks owe us – is that the No voters will vote for the same reason. They are patriotic and they want hope. And they are also doomed by our version of their history. The 18th-century Greeks believed in nationalism born of civilization, an idea that Byron enjoyed but which left out the Ottoman Empire, the wonderful dinar (forget the euro) and a history that has no place in our present narrative.

The 1940s lies like a shadow over Greece today. Those who will vote Yes on 5 July are called traitors – Jermanotsolias (German shirt-soldiers is perhaps the best translation) – while the No voters will be children or grandchildren of the socialist patriots who fought on against the bourgeois-British rulers who took over Athens after Churchill and Stalin agreed that Greece would stay on our side of the Iron Curtain. The puppets and their masters are irrelevant.

Alexis Tsipras is – and here I quote an economist friend – the spoiled boy who long ago managed to get on television with his interviews supporting students, his “face sweet, he was angry and aggressive”, his career spent in the internal politics of the left, zero experience of the real world.

Yanis Varoufakis (this from a less economic and far more political Greek friend) is the ever-smiling economy minister, a “narcissistic idiot”, a far-too-fond-of-his-own-voice show-off student-academic – that’s why Madame of the IMF wearingly insisted on talking to “adults” in her best civil service voice a few days ago – who thinks he can play with the big boys and girls in Brussels without realising that they don’t care about his performance.

The problem here: Europe – perhaps we should say “Europe” in quotation marks – is a bit like the 1930s Europe of Yanis’s grandfather’s era, far more worried about socialism and Marxism and workers’ power than it is about democracy. That’s why it has decided that 5 July's referendum is about Europe rather than democracy. Did not Christine Lagarde say that she hoped the vote would indicate “clearly” what she called “a path”?

You don’t have to be in Athens many hours to see how the image of history has changed. In earlier years, I admired the brass plaque in the Grande Bretagne Hotel which reminded guests that this was Nazi headquarters between 1941 and 1944. Now it is replaced by a gleaming (and equally brass) plaque telling clients that this was the headquarters of the Greek army between 1940 and 1941. No hint of what happened to the Greek army in 1941.

The “split” which our journos suspect may prefigure another civil war here – Elas versus the royalists, backed by the Brits – is not so clear-cut. But if you talk to the Yes voters, they tend to be civil servants, pharmacists, small shopkeepers – let us now analyse those who voted for Hitler in 1933 – while the No men and women are more emotional, more mindful of history, constantly reminding you that the last time the unbalanced, fragmented pension system was “modernised” was 14 years ago. There are hungry people, they tell you, and many are those who remind you of Greece’s 1941 famine. 100,000 dead, perhaps? And we all know who occupied Greece then…

And yet, there is also something dark and dangerous and all too relevant about those days. Europe – from the perspective of Athens – is a very dictatorial institution. It cares less about democracy than it does about money. And faced with the disintegration of the euro, it cares more about money than it does the voice of hungry Greeks.

Tsipras may talk about Europe’s leaders “blackmailing” the voters of Greece – but when those same factotums dictate what 5 July's referendum is supposed to be about (staying in or outside the glorious People’s Republic of Europe), it’s hard to disagree.

Yes, we would all like the Greeks to talk like Euclid Tsakalatos, Greece’s chief negotiator in Brussels – whose Europeanism is emphasised by his brilliant English (courtesy of St Paul’s School and Oxford). “A classic UK academic,” a Greek banker told me at breakfast, “a very nice person, totally unsuited for any political role.”

But then the conversation turned nasty. No such poison in the political lexicon since the Second World War. There are Stalinists inside Syriza, “including the minister of development who thinks Putin is the continuation of Stalin”.

This description came from a man – humorous, a no-hoper with a smile, the kind you come across during revolutions – who insisted that there was a real danger of “political collapse” in Greece.

“The economic collapse has already happened,” he said – we were interrupted by a beggar refugee whom I thought was a Syrian but who was an Afghan, another part of the Greek story – “but the IMF has miscalculated badly. What’s at risk now is political stability, democracy and public safety. The banking system will collapse next week – banks will go into liquidation, private deposits will disappear. We will be unable to buy and sell internationally – and locally.”

There will be those who will vote Yes on 5 July because they are afraid. There will be many, I suspect, who will vote No for the same reason. And there are extremists (how apt this word is in the Islamist sense) like Golden Dawn who blame immigrants rather than Germans for their predicament. And let’s not forget the 4 per cent of the nationalist vote who are in Tsipras’s government with 14 members of parliament. But who is to blame?

“Our populist past,” my banker friend announced firmly. “It started with the military dictatorship, the constant pampering of our lower feelings – that we can do no wrong. The idea that we are the chosen people. This is what destroyed our public finances. It was a very bad idea to join the euro – we thought: ‘Finally, we have received our destiny, we have joined the West.’ But our economy was unsuited to this.”

Oh yes, indeed. And corruption, I added (his banker’s face beamed). “All those centuries of admiring classical Greece,” he said. “Byron has a lot to answer for.”

But there are bigger questions of course. How can we go on admiring the dictatorship of banks (European ones, not Greek)? How can we go on beating our chests with talk of “democratic Europe” when Europe – not Greece – tells the Greeks what their referendums are about? If this “democracy” doesn’t work in Europe, how is it supposed to work in India? Or the Middle East? If we only want people to say Yes on 5 July – Yes or else – who are the dictators?

Is this a bit too much? An old friend, “Monty” Woodhouse, SOE’s operative in Greece during the German occupation – many years later, this young reporter and Woodhouse jointly pursued the wartime record of a certain Kurt Waldheim, former UN Secretary General and a Wehrmacht intelligence officer in the aforesaid Grande Bretagne Hotel in Athens – once wrote that he loved Greece when he realised that “living people still spoke Plato’s language”.

But therein, I suspect, lies the flaw. We all love Plato. And Aristophenes. Did not the frogs croak ‘Rakak-coax-coax-coax’? Why, they Hellenised the Romans, for God’s sake. And we took all this to heart. And we thought the Greeks were our friends, didn’t we?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies